“Make It Big” was Centre Clark’s recent retrospective of the late Mathieu Lefèvre, who studied and worked in Montreal before moving to New York City. As retrospectives go, it was unusual, because it did not feature a selection representative of the life’s work of an established artist. Lefèvre died in 2011 at age 30, after being hit on his bike by a flatbed truck in Brooklyn. This is a retrospective of a life cut short.

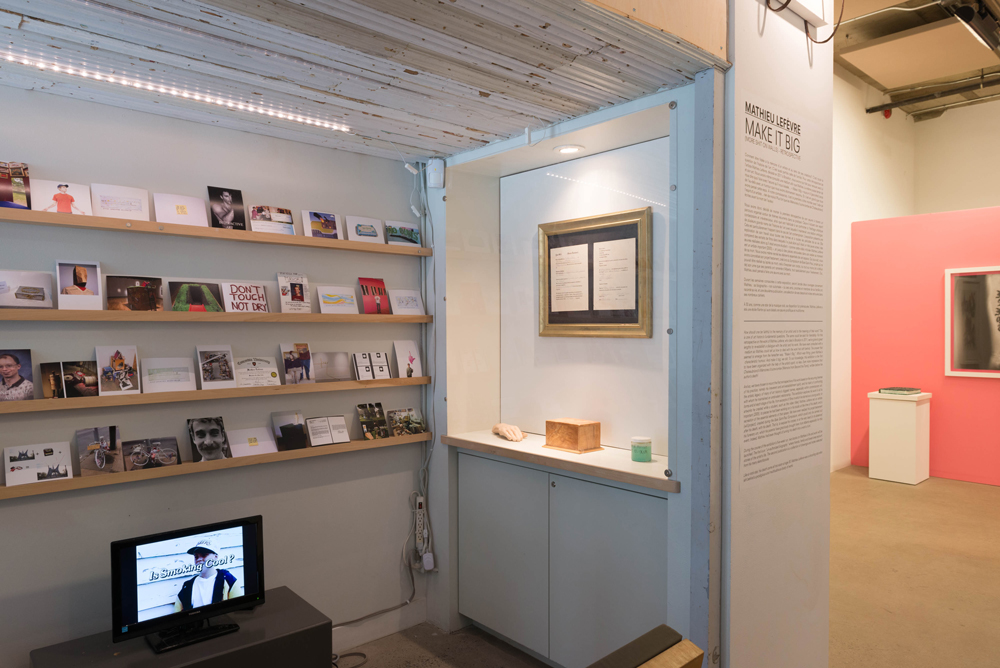

“Make It Big” was also a personal memorial to Lefèvre, who was a Centre Clark member. The curators—Centre Clark’s Manon Tourigny and Roxanne Arsenault, and art critic Nicolas Mavrikakis—designated the gallery foyer this purpose. An urn containing Lefèvre’s ashes rested in an alcove, and nearby were shelves of postcards depicting various projects and artifacts from his life. Visitors could also watch a number of Lefèvre’s video works going back to art school, and childhood.

The foyer of Mathieu Lefèvre’s exhibition, including his ashes, at Centre Clark, 2016. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

The foyer of Mathieu Lefèvre’s exhibition, including his ashes, at Centre Clark, 2016. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

The curators even consulted a medium to channel Lefèvre’s spirit, and thus to glean his feedback on the show. A video of the conversation between the curators and the medium played in a cubbyhole above the foyer, which visitors could access via a short wooden ladder. The retrospective’s title derived from Lefèvre’s comments via the medium.

Lefèvre worked chiefly in paint, which he deployed like icing in a child’s fantasy—in wet, goopy, primary-coloured beads and layers. He also used kitty litter, chewing gum, toilet-paper tubes, and other objects and substances. Most of his works are conceptual, invoking the history of art, and often textual, confronting the viewer with witty aphorisms. On the surface, many are pointedly skeptical of art and the art world.

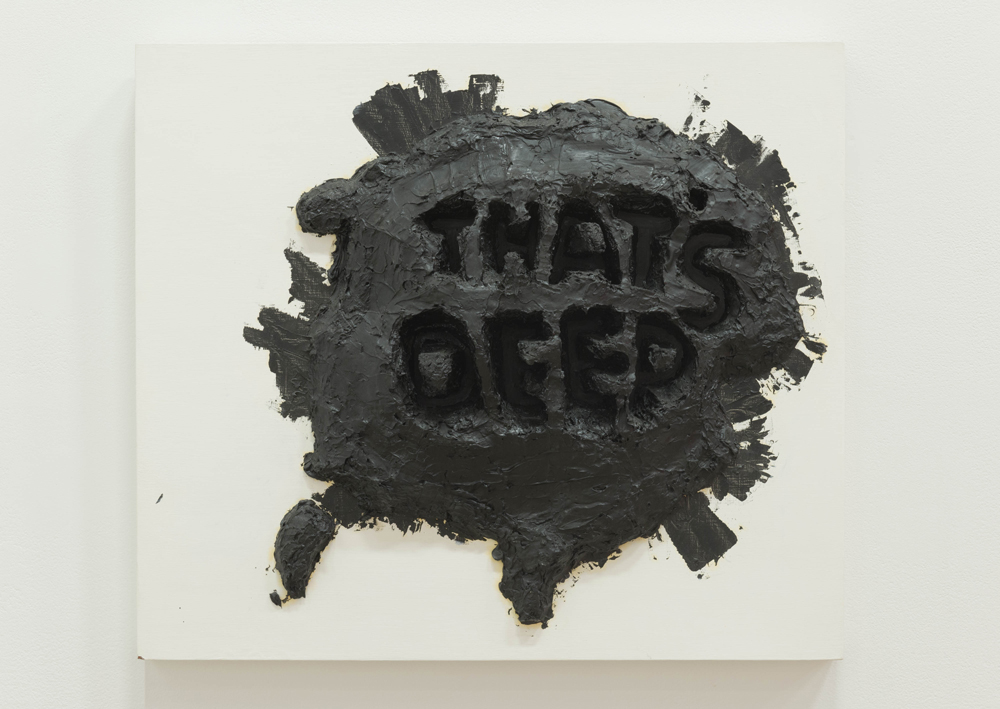

Lefèvre could be positioned as a critical voice, then, but many of his painted aphorisms—such as That’s Deep (the titular text deeply carved into a fat splotch of black paint) or How Do I Make This Look Like Contemporary Art—show little depth. Critique like this comes off as easy and winking: the flings of a rebel or bad boy whose wish to shock and offend is only slightly less strong than his desire to be loved.

Mathieu Lefèvre, That’s Deep, 2010. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Mathieu Lefèvre, That’s Deep, 2010. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

But it turns out Lefèvre issued clues to help viewers undermine or deconstruct his own work. One-Liner—a gooey, multicoloured bead of paint across a blank canvas—is basically an explication of Lefèvre’s approach. If his critical offerings seem glib, it’s because he knew it, and wanted it that way. Critique was not a goal or endpoint for Lefèvre, but simply another medium: paint from a tube.

Throughout “Make It Big,” a picture materialized of a young artist striving to understand the system in which he worked—to master it, to perfect it. Indeed, Lefèvre’s most interesting works are the ones that don’t attempt the rebel stance. In Persian Rug, he simulates a Persian-style carpet with liberally applied oil paints, proposing a web of links between traditional craft and industry, perhaps even taking a swing at Orientalism in art-historical painting. In Tiger Carpet, the figure of a tiger built up out of abundantly applied orange and black paint seemingly attacks an otherwise blank canvas from above. The readings are contradictory: Is this a fearsome predator or a hunter’s trophy? Is Lefèvre’s an aggressive stance toward art-making—or self-doubting dread of the blank canvas?

Mathieu Lefèvre, “Make it Big” (installation view at Centre Clark), 2016. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Mathieu Lefèvre, “Make it Big” (installation view at Centre Clark), 2016. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Boredom Desk, a wooden school desk fastened to the wall with an abstract tableau in chewing gum on the desktop’s underside, reimagines the “great works” of abstract expressionism as casual schoolroom rule breaking. In History of Painting, an art-history textbook created out of layers of paint, the artist’s stance is ambiguous. This “book” is a decadent, richly iced cake, a saccharine, jokey refusal of a canonical text, yet also awaiting consumption—a treat.

Mathieu Lefèvre, Boredom Desk, 2008. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Mathieu Lefèvre, Boredom Desk, 2008. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

A reconstruction, or reimagination, of Lefèvre’s studio occupied a room toward the rear of the gallery. A black-and-white photo of the space was on the back wall, surrounded by various artworks and studio items (desk, crates, buckets). The effect was museological (look but don’t touch) and sepulchral (respect the dead). Here, “Make It Big” straddled a line between retrospective and hagiography. The notion that “Mathieu would have liked it this way” was used to explain various curatorial decisions—consulting the medium chief among them. Such excesses, true though they may have been to Lefèvre’s approach, are one reason why “Make It Big” positively sung as a memorial, yet faltered sometimes as an exhibition.

Yet this love for Lefèvre is something even I, someone who didn’t know him, was affected by. Lefèvre’s smiling, moustachioed face appeared again and again in the show, rife with a certain charm, youthful bravado and irrepressible sense of humour. I found myself wishing I had been his best friend. For all the jokes and humour, all the fun stuff—Lefèvre certainly appreciated fun—the profound sadness of his death was everywhere.

One subtler dimension of this sadness concerns Lefèvre’s ordinariness as a young artist. Looking from a distance, his particular kind of savvy isn’t all that unique: the rebel posture, the critical affectations, the art-historical gags—every art-school cohort has them. The spectre of art school haunts this retrospective, as it does so many artists in the years following graduation. Just outside the “studio” area visitors encountered the video Mathieu Lefèvre est un artiste important (Mathieu Lefèvre Is an Important Artist). In making the video, a school project, Lefèvre approached various Montreal curators and arts administrators, seeking their testimony, documentary-style, to his artistic talent and influence. Most hadn’t heard of him then, and not everyone agreed, but several did (including, amusingly, one of the retrospective’s curators, Roxanne Arsenault).

Mathieu Lefèvre, Mathieu Lefèvre est un artiste important, 2005. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Mathieu Lefèvre, Mathieu Lefèvre est un artiste important, 2005. Courtesy Centre Clark. Photo: Paul Litherland.

The video proclaims Lefèvre’s resolute dedication to success, the muscularity of his ambition. He made calculations. He created a persona, deploying his humour and charisma and enlisting allies. He wanted gallery representation, and, having secured it in Montreal (Galerie Division) and Toronto (Angell Gallery), sought it in New York. He made sacrifices, real (relocating to New York) and symbolic (tattooing himself with the names of painters he admired, like Manet and Watteau; photographs of these tattoos appear in this show). He worked hard in his studio. He seemed to be an artist who knew exactly what he wanted.

The notion that Lefèvre’s ambition would have materialized into further success is mere speculation. Success is elusive, and, once attained, fleeting; in contemporary art, there are many Jack Goldsteins. On Lefèvre’s success as an artist after death—his capacity not to disappear—there is no guarantee. His inward focus upon art, the art world, and his place in it will captivate some, and strike others as immature. Had Lefèvre lived longer, his work might have broadened and grown up a bit.

For this reason, the inheritors of his estate will need to consider carefully if and how they will manage gifts and sales in the world of museums and auction houses. Such decisions will factor importantly, because while Lefèvre had a few years of very active production (chiefly 2009–11), he did not leave behind a large body of work. Ambition and dedication go a long way, and, as this retrospective demonstrated, so do the hopes and wishes of family, friends and colleagues. But in art, there’s nothing like a good business plan.

As the medium explained to the curators, Lefèvre’s first preference of venue was Montreal’s Musée d’art contemporain. While overtures were made both to that museum, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, nothing has materialized yet. Perhaps Lefèvre had not established himself sufficiently to expect such results. But even though he is gone, an exhibition like “Make It Big” exemplifies the persistence of his career. If not today for the Musée d’art contemporain, maybe tomorrow.

Born in Winnipeg and based in Montreal, Edwin Janzen is a writer, editor and interdisciplinary artist working in digital print, video and artist books. He completed his MFA at the University of Ottawa (2010), and holds a BFA from Concordia University (2008) and a BA (Byzantine history) from the University of Manitoba (1993).