At the opening for “Forgetting the Hand,” the Marcel Dzama and Raymond Pettibon show now on view at David Zwirner Gallery in New York, visitors squinted at the drawings tacked to the wall, trying to match the art with the artist. The careful scrawl that read “Time Is Like Water” seemed to be Pettibon’s handwriting; bats are a recurring motif in Dzama’s work, so those bats must be his. And yet, definitive credits eluded us—turns out that scrawl was Dzama imitating Pettibon’s distinctive style of writing, and the bats were Pettibon imitating Dzama’s motifs. “You want to know,” Lucas Zwirner, editor of David Zwirner Books, told the crowd, “who did what.” But you couldn’t.

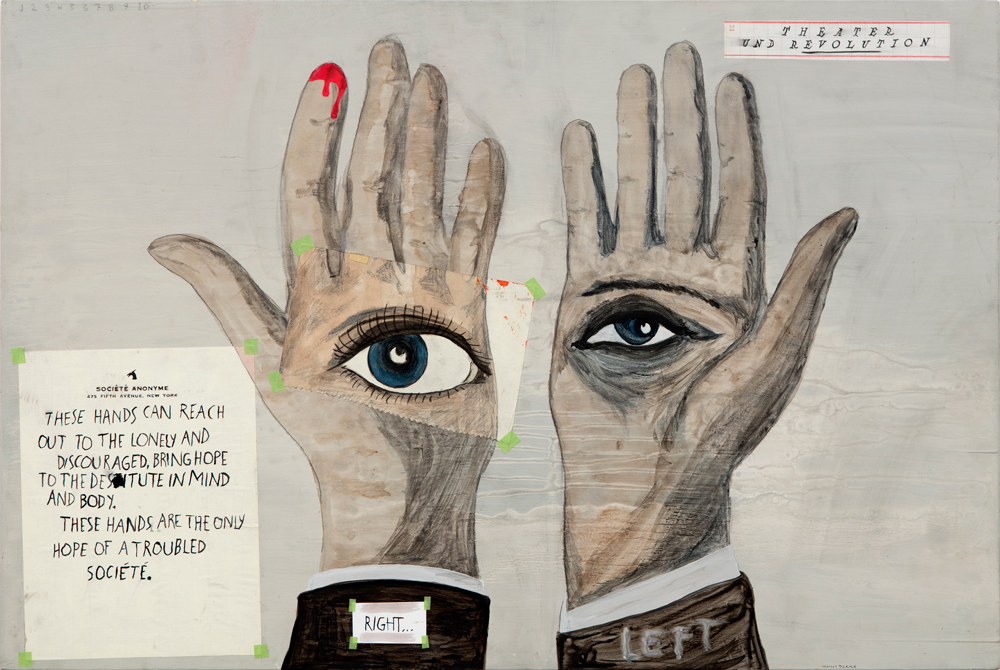

As the title suggests, “Forgetting the Hand” is intended this way. We aren’t supposed to think about who drew or wrote or painted what. This is an elaborate game of exquisite corpse, passed back and forth between the artists until a collaborative conclusion is reached.

“Forgetting the Hand” was originally conceived as a zine between the two artists, of which a limited print run of 300 sold out at the 2015 New York Art Book Fair. The Zwirner show keeps that momentum going, with an accompanying, revised-and-expanded version of the zine, featuring an original essay by poet Andrew Durbin. Half of the works in the gallery were produced in the two days before the opening, with Dzama and Pettibon painting right on the walls. In one corner, a painting of a woman and child peeking inside a swirling blue-and-green wave takes up almost the entire height of the wall. They’re looking at a surfing woman, her hand extended for balance. Below her, on the ground, there are accompanying blue-and-green marks from where the two artists worked together, splattered on the ground.

As partners, Dzama and Pettibon are well-matched. Both of their careers are marked by culturally shared visual references. They favour icons and cartoons, fables and morals. The Winnipeg-born Dzama, whose work has been exhibited internationally and who collaborates with unexpected partners, such as comic and writer Amy Sedaris and choreographer Justin Peck for the New York City Ballet’s upcoming The Most Incredible Thing, often creates cowboys, astronauts and bats—living symbols of flight. Pettibon, long associated with the punk band Black Flag as the designer of their repeatedly referenced black-bars logo (he also illustrated the iconic cover for Sonic Youth’s 1990 album Goo), often depicts surfers, trains and dicks—varying levels of movement.

Combined, the effect is intricate and intimate to the point of claustrophobia. Each piece is full, packed with messages for each other. A Disney dwarf takes a machete to The Incredible Hulk in one, while Batman and Robin stand in a strong stance on another, the words “Fighting crime is just a way to meet guys” printed between them. One of the newest pieces depicts David Bowie in his “Diamond Dogs” days; below him, Felix the Cat holds up a key, but there is no door. One piece, drawn on Chateau Marmont letterhead, shows a black-and-white dog with a forlorn face. “A dog is a man’s best friend,” is written by the dog’s downward pointing nose. Above his head, beside figures that could be human or animal or some combination, is “A man is the product of his whole experience—how we come to be what we are.” Another painting shows a woman’s head held in a man’s hands, a cloth covering her mouth and a terrified expression in her eyes, while a somewhat clunky paraphrasing of Margaret Atwood’s damning truism appears above her: “Most men fear getting laughed at. While most women fear rape and death.” Nearby, on the same hotel letterhead, a small man sits in a small chair, holding his dick. “Don’t go home with a hard-on”: seemingly part advice, part admonishment.

Lucas Zwirner spoke at length about the way Dzama and Pettibon easily adapted each other’s vocabulary, making the collaboration less a battle over territory and more a conversation founded on generosity. Even as they assumed each other’s motifs, they were still creating something new together, like the hand with a pencil piercing through it, which, in direct opposition to the show’s title, seems impossible to forget, perhaps predicting how visitors are going to scrutinize every element for credit. Here is the hand, here is the pencil, here is the pain of proof.

The generosity that Zwirner refers to is one that exists between the collaborators, not between the art and the looker. Dzama and Pettibon’s dense drawings don’t invite us in; this is art for eavesdroppers. We’re meant to overhear (or oversee) the conversation that happened just before we got there, the back-and-forth between two artists familiar in their own identities but not yet as a duo. The immediacy of these new works is particularly suited to such a distinct form of voyeurism, as is the anxious density of each piece. The experience reminded me of an enclosed space, a crowded subway car or elevator that invokes a fight-or-flight response. I felt as though I was listening—or seeing—two artists arrive at the same destination through their different, preferred modes of communicative transportation.

I can forget the hands, but not the voices. Dzama and Pettibon seem to anticipate my eavesdropping. One print protests, “This is not what I want to say,” before conceding they know why I’m listening. “However justly felt and brilliantly expressed.”

This article was corrected on February 29, 2016. The original copy indicated that Pettibon was a member of the punk band Black Flag. In fact, his brother is a member of the band, and Pettibon has long been associated as a creator of covers, posters and other related items for the band.