Who was, and who is, Lawren Harris? The Art Gallery of Ontario has finally opened their long-anticipated exhibition of the leading Group of Seven member’s work, which travelled the US last year with a stay at LA’s Hammer Museum. There, actor, musician and writer Steve Martin helped to initiate the project with deputy director of curatorial affairs Cynthia Burlingham. Here, the AGO’s curator of Canadian art Andrew Hunter collaborates. During last week’s press conference Hunter stressed the need to present Harris differently in Canada, because we supposedly know his clipped, cooly-hued landscapes so well. In part, claimed Hunter, this need is expressed through a more “political” exhibition.

“The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris” is divided into three sections: his quaint paintings of Toronto’s immigrant, working-class Ward district, coupled with period documentation and contemporary works by Tin Can Forest and Anique Jordan; his famous depictions of icebergs and landscapes, which formed the meat of the US show; and an amorphous last section featuring Harris’s 1936 work Poise (Composition 4), which the curators connect to Toronto’s City Hall design. Additional works by Jordan, and pieces by Nina Bunjevac and Nick De Pencier and Jennifer Baichwal, close the show.

As a whole, we left the exhibition disappointed. Our questions were foremost about the myths surrounding Harris, the received canonical story of Canadian art, the racist, colonial traditions it stems from, particularly its erasure of Indigenous perspectives, and the ability of a contemporary institution to address such things in the context of a blockbuster exhibition.

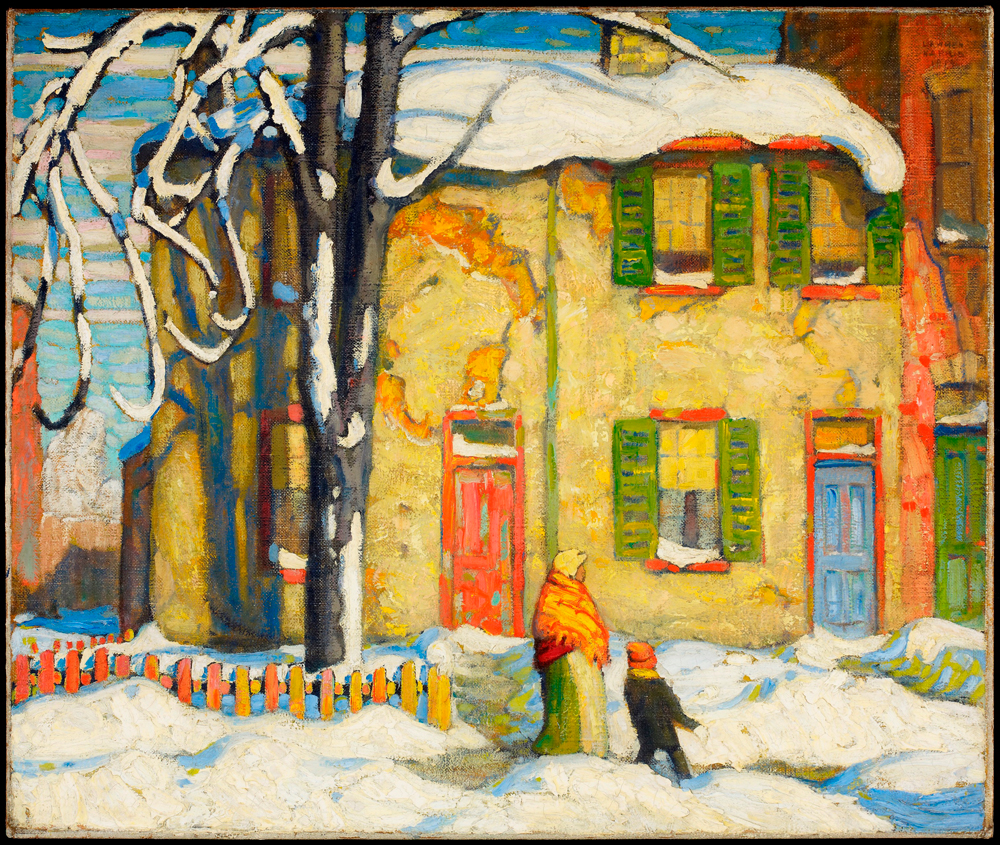

Lawren S. Harris, Old Houses, Toronto, Winter, 1919. Art Gallery of Ontario, gift of the Canadian National Exhibition Association, Toronto, 1965. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Lawren S. Harris, Old Houses, Toronto, Winter, 1919. Art Gallery of Ontario, gift of the Canadian National Exhibition Association, Toronto, 1965. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

How can an exhibition offer a political framework for Harris without including Indigenous artists or effectively integrating Indigenous voices?

During the exhibition’s press preview, curator Andrew Hunter underscored that the exhibition’s Canadian iteration “really upped the political content” through the show’s prologue, the section of the show that focused on Harris’s time in Toronto’s Ward neighbourhood, and an epilogue including four contemporary artists who respond to the work from a contemporary vantage point.

Despite these additions, there was a glaring omission of Indigenous art. The scant inclusion of Indigenous voices was limited to the final portion of the exhibition, where a participatory projection displayed quotes from visitors about their own “idea of north.” Quotes from Glenn Gould and a 7-year-old AGO visitor were included alongside contributions from Inuk throat singer Tanya Tagaq and Inuk writer Alootook Ipellie.

This omission is troubling when we consider the role that the Group of Seven and Harris played in promoting the idea of the Canadian landscape as a terra nullius, where Indigenous lives are omitted and territory is presented as uncharted, foreboding, alienating, yet available.

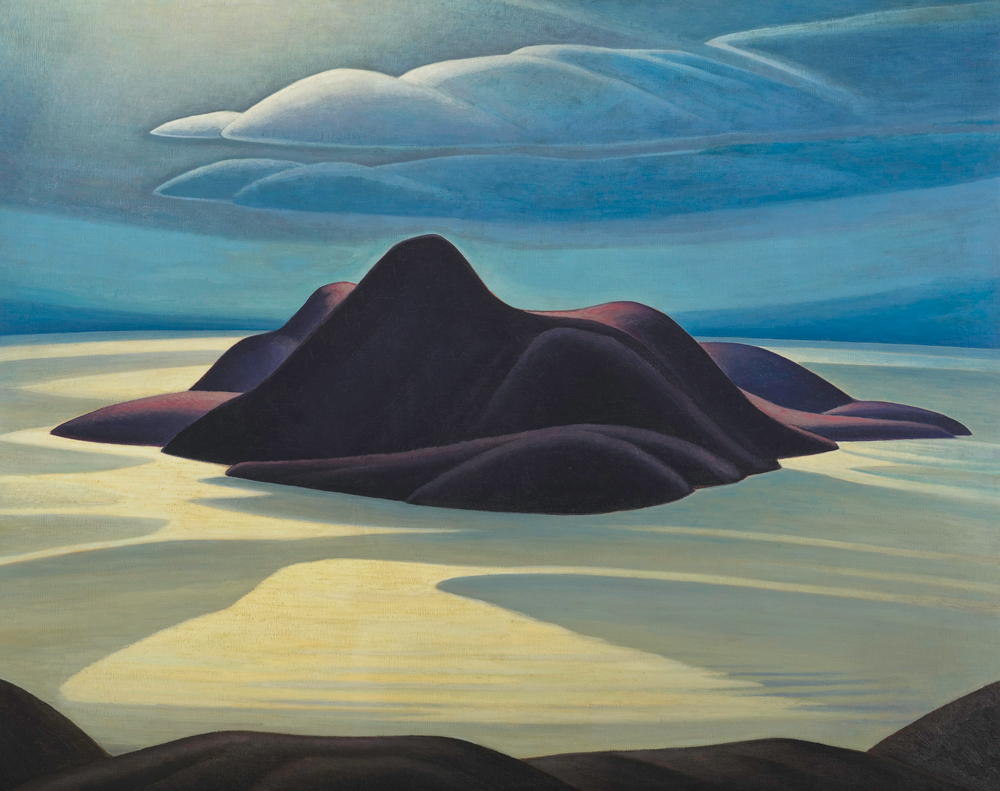

Lawren S. Harris, Pic Island, circa 1924. Gift of Colonel R.S. McLaughlin, McMichael Canadian Art Collection. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Lawren S. Harris, Pic Island, circa 1924. Gift of Colonel R.S. McLaughlin, McMichael Canadian Art Collection. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Several of the exhibition’s didactic panels did acknowledge the erasure within Harris’s landscapes, underscoring his vision of “an empty, cool, modern landscape, devoid of human presence,” and the inclusion of photography of people in these spaces—both by Harris and by other artists—helps to offset some of the romanticization. But, as a whole, these moves felt cursory.

The omission is surprising, especially given the AGO’s apparent commitment, both developing and distant, to deal more directly with Indigenous history and contemporary presence in Toronto, such as the upcoming show “The Toronto Project: Tributes and Tributaries,” co-curated by Hunter and Wanda Nanibush. It’s also surprising given Hunter’s involvement with revisionist showings of the Group of Seven. Hunter’s previous work has underlined, for example, the environmental dimensions of the Group of Seven’s work that had previously been ignored—the fact that some of the Group of Seven artists depicted clear-cut and new-growth forests. An AGO exhibition that Hunter was involved with 13 years ago positioned Tom Thomson within the Arts and Crafts tradition, underscoring the design impulses within Group of Seven paintings, and how they were also informed by Art Nouveau and art deco.

Do Canadian audiences fully understand why Harris has achieved such pre-eminence within Canadian art history? Perhaps that could have been the focus of the show, rather than a reintroduction.

When “The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris” was shown at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, Hunter and Martin underscored that the exhibition served a different function: it was an introduction for those audiences, whereas the Canadian showing is a presentation of the artist in a different light.

Yet while Canadians may recognize Harris’s name, or more likely his images, is there really a widespread understanding of why Harris has such pre-eminence within our cultural history? (A recent Hyperallergic article confirms that more than half of Canadians can’t name a single Canadian artist.)

Even among the Canadians who know of Harris, there are likely a lot of people who are confused as to why he’s important. And this defines our culture as it has been handed to us: our confederated country is so new, and what counts as our cultural identity is so constructed, and often ignorant of larger aspects of what and who we really are.

This can be said of all of the Group of Seven. Why does this work supposedly stand for who we are? Because it was purposefully positioned to do this, and has become shorthand. Indeed, it was designed to be shorthand.

Lawren S. Harris, Lake Superior, circa 1924. Art Gallery of Ontario, Bequest of Charles S. Band, Toronto, 1970. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Lawren S. Harris, Lake Superior, circa 1924. Art Gallery of Ontario, Bequest of Charles S. Band, Toronto, 1970. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

But rather than unpacking this freighted history, the exhibition accepts Harris ipso facto as one of Canada’s most important artists.

Why not, then, make a show deconstructing the legend of Lawren Harris? There are some successful recent examples of this approach. Last year’s Jack Bush retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada was particularly successful at offering a warts-and-all portrait of an iconic Canadian artist. It dove into biography, into Bush’s insecurities, the working relationships he had and his means of production, including his day job as a commercial illustrator, and in this breadth it ended up being much more political—conscious of gender, and capitalism, and all the more fascinating, even playful, because of this.

Why present Harris without fully delving into his social and artistic connections—and all the class-related questions that would raise?

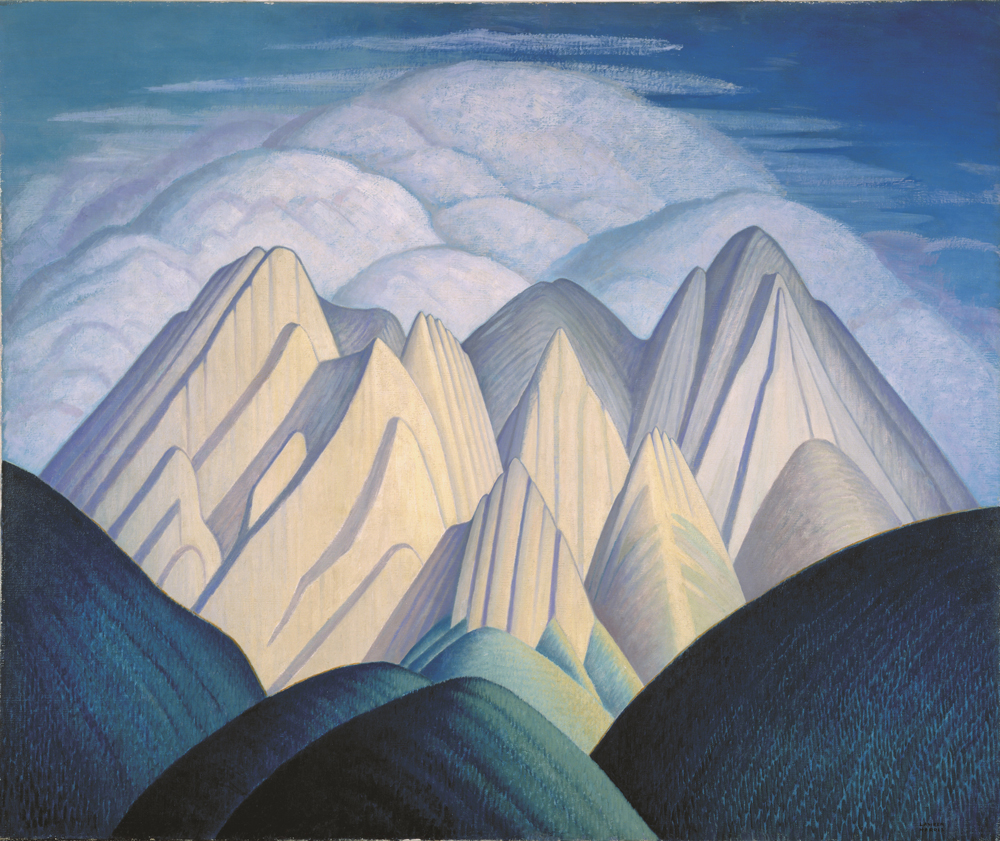

The prospect of unpacking the myth of Lawren Harris leads into questions of other aspects of his work and production. With “The Idea of North” divided into three portions, focused on the Ward, the Arctic and a return to the urban sphere, Harris is presented in a kind of vacuum, where he primarily exists in Modernist-Romantic solitude, in relation to geography.

The backbone of this Harris exhibition is effectively biographical, proceeding chronologically, but we find out very little about Harris the person. For instance, as the galleries transition from slightly abstracted or idealized city scenes into unpopulated mountain landscapes, a clear discussion of Harris joining the Toronto Theosophical Society is skirted, addressed mainly in Tin Can Forest’s video installation.

Obviously, social and commercial relationships inform Harris’s work as well, and the show’s most interesting moments are the instances where Harris’s connections with other artists, other movements, other forms of cultural production, are made evident. But such information is only faintly apparent here. Harris’s pre-eminence largely grew not out of his talent as a painter, but because of his adeptness as an organizer, working to formalize the Group of Seven and their history, financing boxcar trips for the Group to paint in Algoma, and generally setting a lot of the aforementioned mythmaking into motion.

Lawren S. Harris, Grey Day in Town, 1923 reworked early 1930s. Art Gallery of Hamilton, Bequest of H.S. Southam, Esq., C.M.G., L.L.D., 1966. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Lawren S. Harris, Grey Day in Town, 1923 reworked early 1930s. Art Gallery of Hamilton, Bequest of H.S. Southam, Esq., C.M.G., L.L.D., 1966. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Harris’s own subject position is not examined. He may have painted the Ward and spent time there, but this is not social work; he wasn’t of the Ward in any real sense. Harris was independently wealthy, and lived in well-designed Toronto homes on Clarendon Avenue and in Forest Hill. These are more than just accidents or footnotes: it’s essential information for understanding how he was able to make the art that he did. Contemporary exhibitions about canonical figures show their relevance by acknowledging such things, rather than pretending, in a sort of WASPy fashion, that means play no role in cultural production.

Such questions around art and money are more relevant in the context of a summer blockbuster. Summer has become the time for revenue-generating shows at museums. Think of the film industry, where action movies dominate summer, while Oscar contenders come later in the year. Action movies are characterized by evergreen, widely recognizable brands, such as the comic-book characters of DC and Marvel; for museums, the evergreen, recognizable brands are the artists who fetch high prices at market, and can be named by the average person—these tend to be dead, white and male. Such financial incentives are, for the AGO, strengthened by involving a celebrity curator (and the marketing materials focus almost entirely on Martin’s participation). Bottom-line concerns are real in culture-making, extending beyond individual realms of artistic production.

What does the section on the Ward mean in Toronto at this point in time?

“The Idea of North” section on Toronto’s Ward neighbourhood stood out as the most engaging portion of the show. There was supplementary content—maps of the district, photographs by City of Toronto photographer Arthur Goss and works by other artists—that were productively dissonant with Harris’s works. Where Goss’s black-and-white images show condemned houses and abject poverty, Harris’s paintings are comparatively jaunty. There’s a sense that Harris was painting an entirely different neighbourhood, and it illustrates the remove and idealization within his work.

The integration of Anique Jordan’s Mas’ at 94 Chestnut, a panoramic photograph from 2016 that depicts posed black members of a congregation, into the Ward portion of the show was clever in this sense. It points to the exclusion of marginalized histories within “official” national archives and canonical Canadian art, and suggests that other histories are passed down in alternative methods—orally, generationally and so on.

Anique Jordan, Mas’ at 94 Chestnut, 2016.

Anique Jordan, Mas’ at 94 Chestnut, 2016.

The section on the Ward is interesting in light of a surge of recent interest in Toronto’s history (including the recent publication of The Ward: The Life and Loss of Toronto’s First Immigrant Neighbourhood), but more so the deconstructing effect that Goss and Jordan’s photographs have on Harris’s work. At its worst, it suggests how utterly uncontemporary Harris’s work is—how his vision of Toronto, even his approach to the aesthetics of depiction, seems patently conservative.

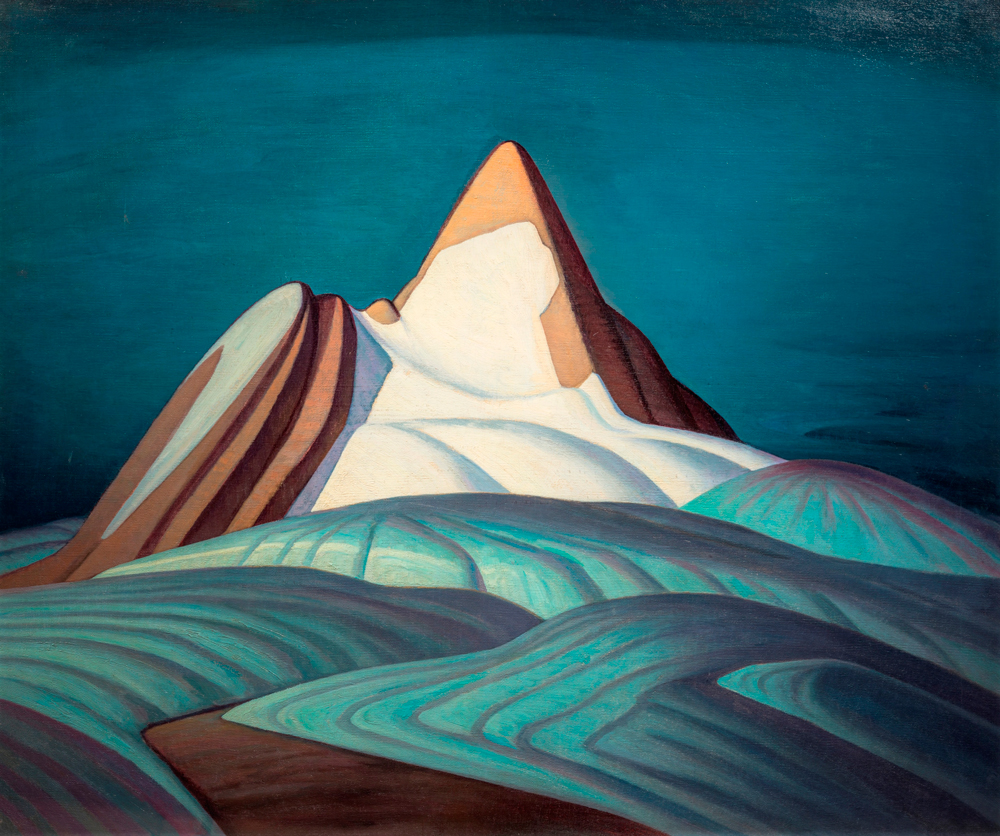

What, ultimately, is Harris’s idea of north?

The title “The Idea of North” makes a necessary distinction: the images presented in Harris’s works cannot be accepted at face value. These are manifestations of an ideal, of a romanticization created by Harris himself. Yet while the characteristics of the idea of north are spelled out—the works are uninhabited, awe-inspiring, detached, transcendental—the sum total of these elements is unsettling.

Lawren S. Harris, Untitled (Mountains Near Jasper), circa 1934-1940. Collection of the Mendel Art Gallery, Gift of the Mendel Family, 1965. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Lawren S. Harris, Untitled (Mountains Near Jasper), circa 1934-1940. Collection of the Mendel Art Gallery, Gift of the Mendel Family, 1965. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

“The Idea of North” is not actually elaborated anywhere in the show, as far as we could tell. In a way this elaboration might have been irrespective of concerns about, say, the Inuit idea of north, the Indigenous idea of north: to wit, what exactly is Harris getting at with his work? We are never really told. A spiritual grounding could illuminate here, but there are darker aspects that the curators seem embarrassed of.

The absence of a clear definition of Harris’s idea, or ideal, of north plays into one of the most problematic aspects of the work: an assumed neutrality of the viewer. For Harris, the neutrality of the viewer was also, paradoxically, his deep subjectivity. In his work he essentially says, I am the person watching and looking; I am the person depicting. But this hyper-subjectivity is that of a formally educated, privileged white male, so suggests or prompts a presumed, exclusive and mistaken neutrality. The silencing of variegated characters and perspectives within and without these paintings is, for good or ill, their point. They are deeply Modernist. And while the presentation of these works in terms of their original intentions does not have to take a Modernist approach, a “political” update needs simultaneously to acknowledge the works’ and their creator’s insularity—and the political ramifications of such.

Lawren S. Harris, Isolation Peak, Rocky Mountains, 1930. Hart House Permanent Collection, University of Toronto. Purchased by the Art Committee with income from the Harold and Murray Wrong Memorial Fund, 1946. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.

Lawren S. Harris, Isolation Peak, Rocky Mountains, 1930. Hart House Permanent Collection, University of Toronto. Purchased by the Art Committee with income from the Harold and Murray Wrong Memorial Fund, 1946. © 2016 Estate of Lawren S. Harris.