What does it take to get inside the mind of an artist?

This is a question that can hover around those of us who look at and think about art. Yet rarely do we find a clear answer. Group shows tend to lean toward curatorial gamesmanship, while many solo exhibitions can seem equally indefinite, offering isolated snapshots of the artist’s thoughts, gestures or fancies of that particular series or moment.

If the mind of an artist must be fixed to a place, then it has to be the studio, where the thinking really gets done. But that’s a privileged space—invitation only, and rightly so. After all, what artist wants a bunch of strangers wandering around in their head?

There are instances, however, when as a viewer you feel like you might just have found a way into that elusive inner space of an artist’s practice—when something special is revealed about the development of a creative sensibility over time. Kristan Horton’s “A Haptic Portrait of Groping Imagination,” curated by Ben Portis and currently on view at the MacLaren Art Centre, is just such a case.

Fashioned as a survey (Horton’s first, it should be noted) the show brings a deft curatorial touch to a selection of works from 1997 to the present. It includes enough to make sense of Horton’s layered, hands-on approach to photography, sculpture, drawing and video, but not so much that you feel overwhelmed.

Yet Horton’s work can be overwhelming—not for its scale, necessarily, but for its accumulative intensity or single-minded drive to the critical core of its subject matter.

Take, for instance, his 2006 stop-motion video Cig2Coke2Tin2Coff2Milk, where product packages are cut apart then meticulously (and somewhat incredibly) refashioned into simulacra of one other. Or consider the epic 2008 series Drawing of the History of the First World War, which illustrates the audiobook version of historian John Keegan’s tome on the Great War in a sequence of eight vortex-like drawings.

In a suite of works from the photo series Dr Strangelove Dr Strangelove—perhaps Horton’s best-known work, created between 2003 and 2006—this intensity comes through again, with Horton pairing stills from Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 Cold War satire with similar images created using everyday objects.

Each of these pieces hinges on Horton’s (and, in turn, the viewer’s) full immersion into the work. They are articulations of the clockwork motion of an artist’s mind in obsessive free fall amidst the intricacies of fact and fiction.

But there’s a simultaneous distancing that happens, too. How many times, you wonder with amazement, did he refashion that cigarette package, or listen to that audiobook, or watch that film? This latent awareness of the material processes and mental mechanics—the haptic relationships—of remodelling, reinterpreting and reconstructing from source to form reminds us of the layered perspectives and malleable realities that shape our impressions of modern life and history.

The sense of full immersion continues in various “portraits” included in the show. Hardly conventional, these works read as experiments in grappling (or groping, as the exhibition title suggests) with ideas of presence and absence.

Horton’s Haptic Sessions is a set of three video works that document the assorted objects connected to the artist’s existence in a particular place and time. Shot between 2009 and 2012 in Toronto, Chicago and Barcelona, each video depicts ever-changing arrangements of found items—rulers, coins, keys, an egg, a pocketknife, a dead fly—spilled onto the surface of a flatbed scanner. Horton animates these objects by touch, their jittering movements onto and off of the screen becoming evidence of a momentary physical connection to an ephemeral state of being.

Similarly, Horton’s 2009 series Orbits may be read as composite records of accumulated identity. These large-scale, digitally layered photos combine at-hand objects—from tools to vinyl records to Canadian Tire money—in stratified, kaleidoscopic arrays. They shift and spiral on illusive depth and meaning, offering an archeology of cluttered material life and a stargazing statement on the infinitely expanding unknown.

While all of this twisting and turning, this layering of existential markers of self, offers various material traces of mind and body, it is Horton’s most recent body of work (portions of which are also on view at Jessica Bradley Annex in Toronto) that hints at an emotive context connecting all the show’s elements.

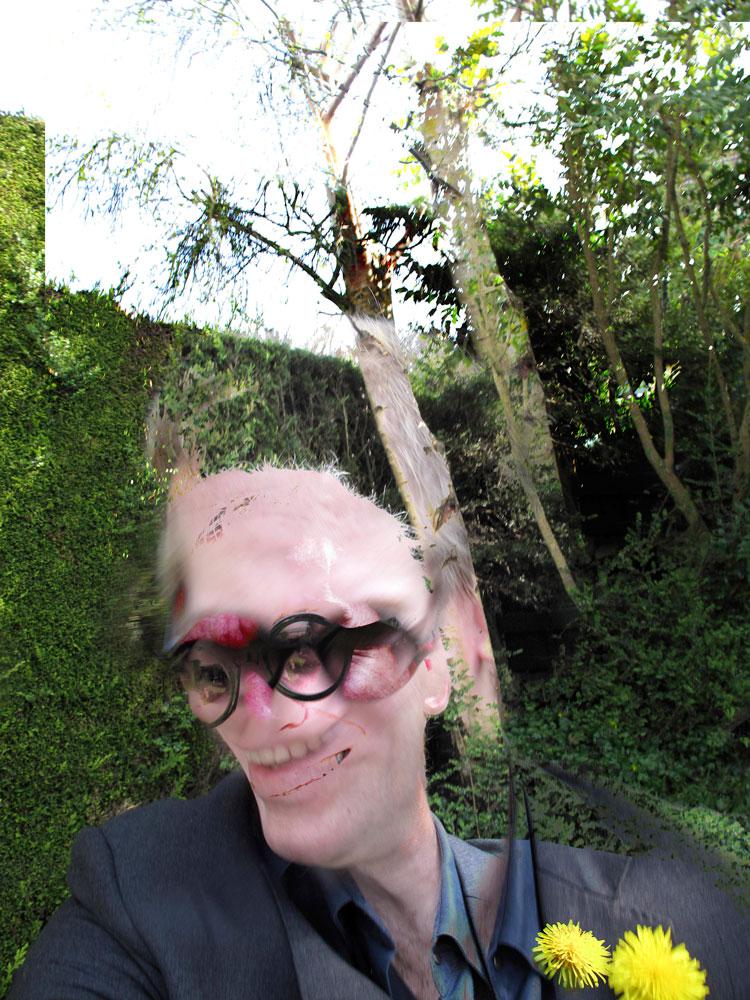

Sligo Heads, the series of large-scale, digitally distorted self-portraits, was begun when Horton found himself transported from a studio in Barcelona to an empty artist-residency complex in Sligo, Ireland. The works capture what Horton, in a MacLaren podcast, has called a “zero state,” an “instantaneous impression” of literal and emotional isolation.

The Sligo works are supercharged images that, in their layered, blurred double- and triple-selves, seem like monstrous hallucinations. Looking at them, one can’t help but see the intensity of Francis Bacon’s most trenchant paintings screaming back.

Yet the title of each of these new images bears a different name or identity. As Horton tells it, these images “are and are not” him. That is, they are somebody, everybody and nobody.

Therein, I think, lies the key to the work and to the show. This may be a peek inside one artist’s mind, but its power lies in a shattered-glass reflection of shared histories, shared experiences and shared existences.

To find out more about Kristan Horton, view his profile in Canadian Art’s artists channel.