Krista Belle Stewart probes the squishy places where collections and archives and image-making meet. It wasn’t clear when first entering her exhibition, “Rip Rap,” at Calgary’s the New Gallery, which category each of the five objects on display belonged to. Every work in the modest show, which closed on May 9, attests to some failure of the traditional organizational schemas around which museums, galleries and archives revolve, and works through the ways making, remaking and unmaking might destabilize colonial images.

A portion of the work in the exhibition, arising from residencies Stewart completed earlier in the fall at the Nisga’a Museum and Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery, has been shown before. The museological referents are clear: the largest work in the exhibition, a four-panel jacquard weaving entitled Sim – real / very (2015), is distinctly anthropological in appearance. The weaving is blown-up from an image in the Nisga’a Museum’s collection (an image which also haunts the neighbouring video work, I Only Went Briefly Beyond and Now I Have Returned), picturing a group of figures dressed in luxuriously embroidered and embellished garments, surrounded on their right by wooden carvings.

The figures pictured are Nisga’a chiefs, all male but one. The mysterious female figure in the image is something of an anomaly, Nisga’a chiefs generally being male. The little that is known about the image concerns its maker, Benjamin Haldane, a Tsimshian photographer who traveled through northern British Columbia and Alaska documenting both his own people, and others of the region. He took the original photo in 1928.

This photograph’s social life has unfolded at the Nisga’a museum, both during and after Stewart’s residency. The Vancouver Sun reports that shortly after Stewart’s stay had ended, a woman from the community came forward to identify the mysterious woman as an important Nisga’a matriarch who temporarily took on the role of chief. It’s exactly this kind of retelling and reassertion of history that interests Stewart, a member of the Upper Nicola Band of the Okanagan Nation, and the Nisga’a Museum is the perfect site to examine it.

Opened in 2011 as a space for objects taken from the Nisga’a nation earlier in Canada’s colonial history, and subsequently repatriated at the behest of the community, the museum upholds a distinctive mandate. Many of its holdings were repatriated under the condition that the Nisga’a nation maintain established standards for the care and conservation of artifacts. Much of this collection was divorced from its original context when it was first taken, and a major task of the Nisga’a Museum is to research and tease out the oral histories related to them.

The museum itself exists at the difficult meeting place of Indigenous sovereignty and colonial erasure, and the photograph Stewart works with exists in a complicated place, too: one where an image that reads as a typical example of the colonial gaze resists the standard narrative of European-photographer-cataloguing-a-civilization-he-saw-as-ending. By representing the image as a weaving (commissioned from Vancouver weaver Ruth Scheuing), Stewart faces the image’s complications head on. She maps another layer of history onto the photograph, reimagining it through the imperfect translation of textile. Rather than presenting the photograph as an objective record of the position of light at a specific, static moment in time, weaving reinscribes the image as a delicate maneuvering of time and material, a process of intentional fabrication and configuration.

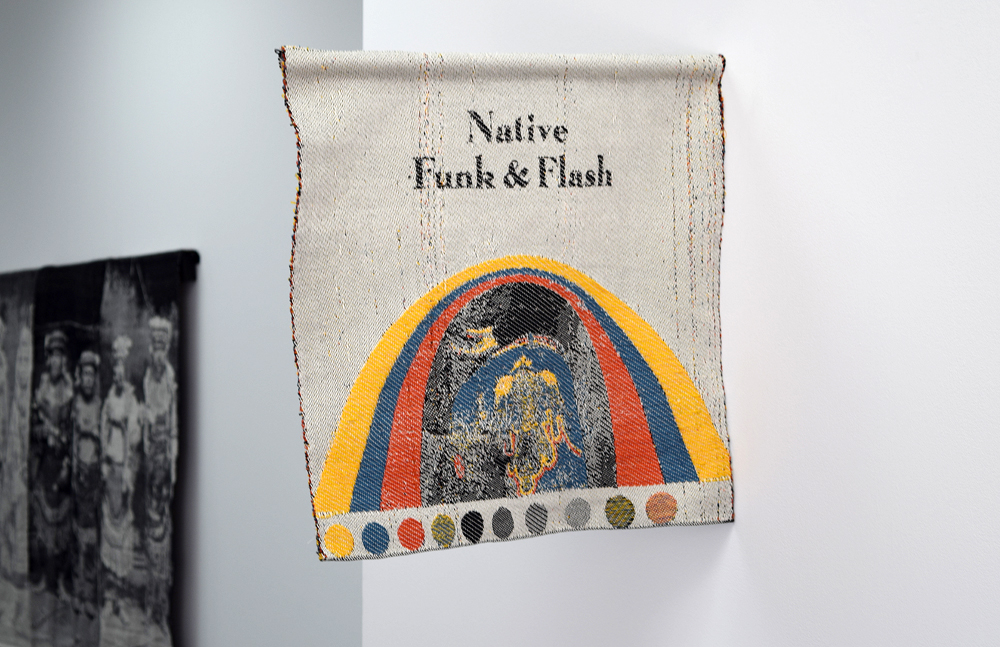

The position of “artifact” was further complicated in the exhibition by the display of Untitled (Handwoven Scarf made by my mother, Seraphine Stewart). The weaving reads mostly as a contemporary object, but, placed across from the larger weaving based on the archival photograph, suggests a tension between practical objects and decorative ones. The weaving at once recalls the tourist-trade value of Indigenous-made objects (and the cultural caché implicit in their “authenticity”), and rejects notions of what Indigenous craft should look like. The varied thickness of the fibres and the intuitive changes in pattern evoke the metaphor of weaving again—weaving as accumulative, the ins and outs of threads as the formation of a pattern of meaning. Elsewhere in the gallery, a small weaving titled The Future is but the Obsolete in Reverse, hung out from the wall so as to expose both its front and back, includes the text “Native Funk and Flash.” This reference to a 1974 fashion book of the same title was not immediately apparent; instead, rushes of colour obscure all semblance of representational imagery. On its back, a multicoloured mass of threads blots out the text, too.

In Stewart’s collage and video works also in the show, the same careful disruption of the image’s representational quality thrives. Her source material is archival or museological, but in both the video and the collage her cuts obscure, return to the personal, make reference to the image’s life in its context (and to the way that life has modulated over time, alongside changes in place).

The exhibition’s title,“Rip Rap,” made a clear insistence on the land: rip-rap refers to rocks and stones that border a shoreline to form a barrier against erosion. But the softer associations of the words “rip” and “rap” also conjure remixing, storytelling, disruption, pulling or teasing out threads from the tangled, knotted mass of history. In Stewart’s work, weaving involves ripping back into an image, obscuring or messing with its original intent by puckering the fabric, displaying the heavy-threaded versos, revealing the glitches and imperfections inherent in the process of image-making and remaking.