A poignant grande dame shown lost in memory in a lonely château is a fairly familiar image around Rochechouart in central France. Dour pictures of the novelist George Sand from the mid-19th century on are found at her manse-turned-museum just north of La Châtre to the east. A recent Gala magazine showed an unsmiling Bernadette Chirac about to prepare drinks for ex-president husband Jacques at their Château de Bity in the Corrèze area to the south. The subtext: château life is empty luxury served on the rocks.

But this fine old ennui gets a cheeky contemporary spin at the Château de Rochechouart, west of porcelain-making Limoges, when visitors are faced with the mascara-drizzled cheeks of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, the grand drag-dame in Kent Monkman‘s installation The Collapsing of Time and Space in an Ever-Expanding Universe. Strictly speaking, the sorrowful Miss Testickle is meant to be imagined in her Paris apartment, her glam recording career far behind her. But the airlessness in Monkman’s detail-perfect installation is pure mid-France château, its gloom as thick and impenetrable as the walls.

How this Toronto artist came to central France, bringing Miss Testickle, his drag alter-ego, with him, is not the story here—even if, startlingly enough, this is Monkman’s first solo museum show in Europe. (He’s in demand this year. His installation Bête Noire, shown this spring at Sargent’s Daughters in his New York solo-show debut, travelled to Site Santa Fe this summer.)

Annabelle Ténèze, the boundlessly energetic curator of the Musée départmental d’art contemporain de Rochechouart, housed in the historic 12th-century château, says she first encountered Monkman’s work in Toronto in 2008 and has kept her eye on his practice since. She’s been drawn to his “concern with the contemporary reality of hybridizing cultures in our present global economy,” as she notes in the exhibition brochure for “Kent Monkman: L’Artiste en Chasseur” (“Kent Monkman: The Artist as Hunter”).

The musée itself is certainly a desired destination for artist and art fan alike. Its Europe-wide reputation is based mostly on its substantial archival collection of collage and sound poetry by Raoul Hausmann, the Vienna-born Berlin Dadaist who spent time near Limoges avoiding Nazis during World War II. Works by Rodney Graham, Giuseppe Penone and Gerhard Richter are also in the collection, though. Tourists can also see merely getting there as an adventure. Driving to the nicely sited building overlooking the meeting of the Graine and Vayres Rivers requires advanced motoring skills to navigate the endlessly twisty and narrow French backroads.

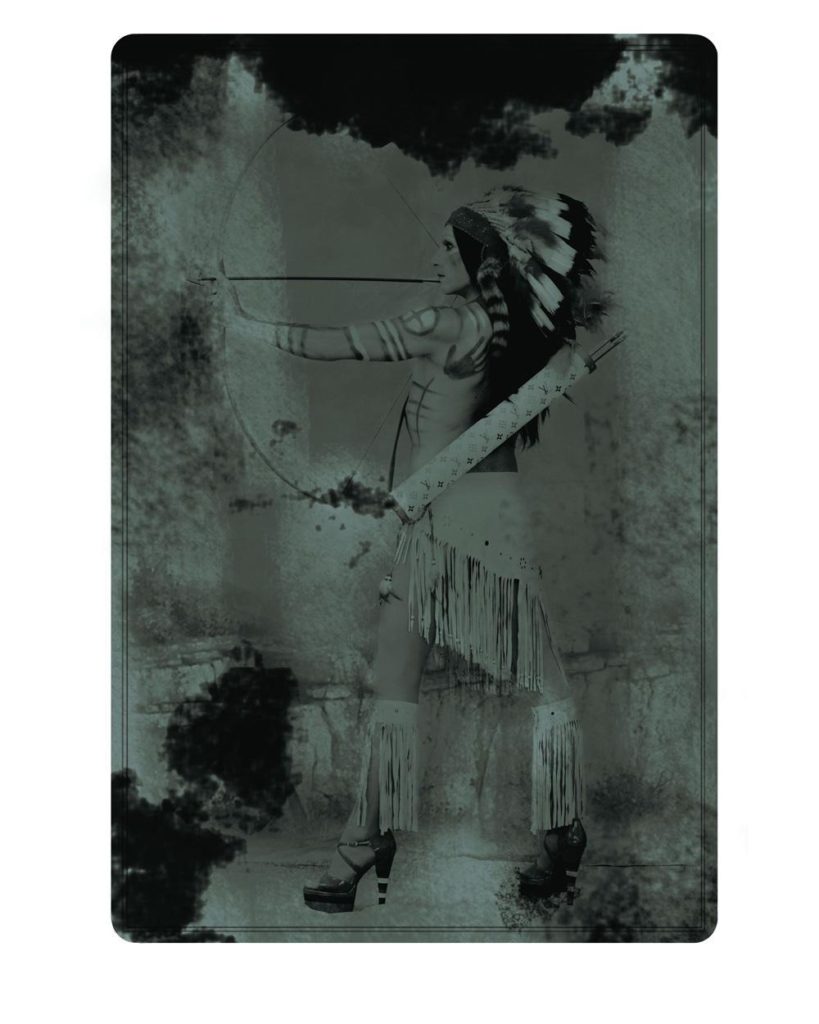

But main story here is how “The Artist as Hunter”—an exhibition drawing deeply on the artist’s knowing, smartass appropriations of the North American “noble savage” as envisioned in media from 1910s Edward S. Curtis films to 1960s CBS cartoons and beyond—inhabits one of France’s more important châteaux in such a proprietary fashion. Monkman’s work looks as if it was made for these walls and halls, from the aged-in-aspic look of his Emergence of a Legend series of faux-daguerreotypes depicting Miss Testickle’s early years, to the installation of her quiver and assorted hunting gear in the château’s hunt room adorned with Renaissance murals. Monkman’s signature crystal tipi is housed in all its shimmery splendour in the château tower.

“Aspects of French bourgeoisie have popped up in my work with the adoption of Louis Vuitton as Miss Chief’s chosen luxury brand, and references to the fur trade,” the artist helpfully explains in an email.

A central gallery lined with Monkman’s large-scale painted riffs on idyllic North American landscapes is reminiscent of the way tapestries from nearby Aubusson have been hung in many châteaux over the years. Monkman’s flattened figures in the paintings and the motivic repetitions from one canvas to another recall elements found throughout historic tapestry production in the area. I leave it to historians to consider his narrative of the Lone Ranger and Tonto about to have an al fresco foursome with two muscular Indian dudes in relation to the famous Dame à la Licorne series found in the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

Nevertheless, “The Artist as Hunter” is every bit as much about cuir culture (as in French leather) as queer culture (also as in French leather). We’re in cattle and hunting country. The Rochechouart family—with an entitled status to almost rival that of the French royal family—has also been among the country’s hardiest and most pugnacious lines, going back over 800 years to the very early Crusades.The château’s entire haute bourgeoisie vibe and its historical place in macho French culture play perfectly into Monkman’s hands and imagination.

“Hunting themes have been present in my work for many years. In early discussions with Annabelle, we were excited as the ‘artist as hunter’ theme emerged to bring focus to the survey of my work and fit the context of the château,” Monkman continues. “My work has challenged the macho subject of the history of North American art by John Mix Stanley and others, who painted themselves in their work as hunters or created cowboy-and-Indian mythologies.”

The Rochechouart show also offers the artist an extended critical context in his work, casting it back to its pre–North American European roots. Karl May’s late 19th-century German adventure stories featuring Old Shatterhand, the European adventurer, and Winnetou, his Apache sidekick, are referenced by several of Monkman’s paintings in the show.

“The work alludes to the long tradition of Aboriginals performing for Europeans in Europe from Wild West shows to others,” he adds.