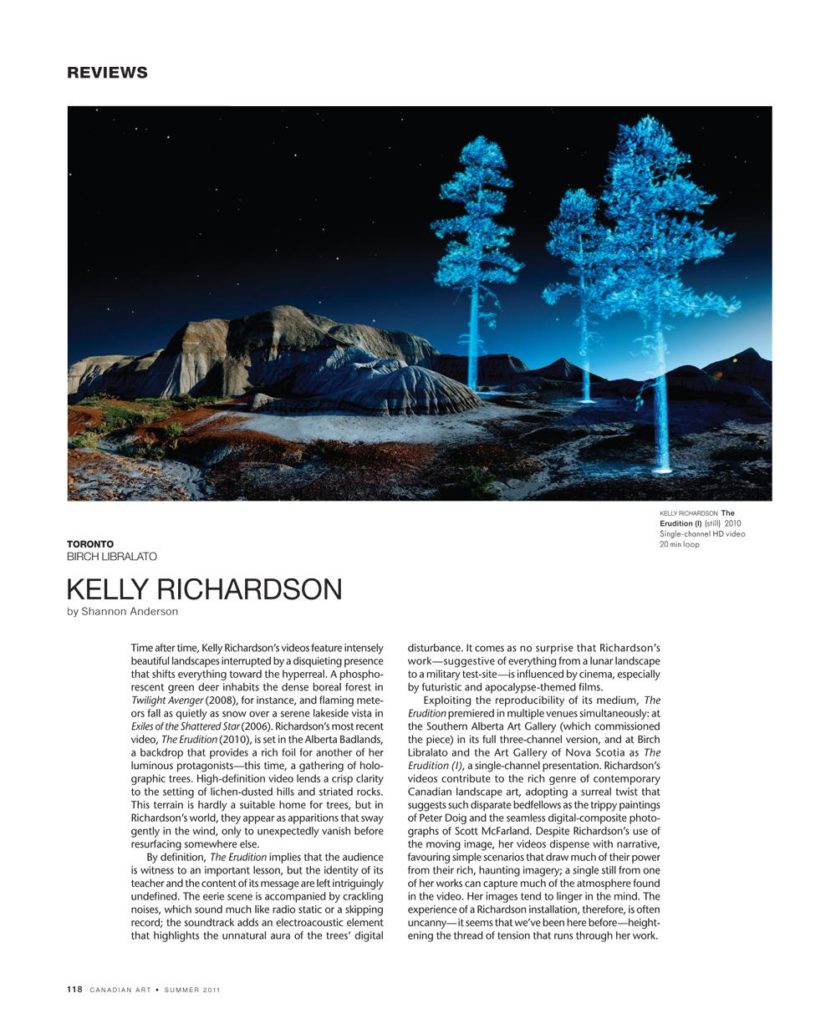

Time after time, Kelly Richardson’s videos feature intensely beautiful landscapes interrupted by a disquieting presence that shifts everything toward the hyperreal. A phosphorescent green deer inhabits the dense boreal forest in Twilight Avenger (2008), for instance, and flaming meteors fall as quietly as snow over a serene lakeside vista in Exiles of the Shattered Star (2006). Richardson’s most recent video, The Erudition (2010), is set in the Alberta Badlands, a backdrop that provides a rich foil for another of her luminous protagonists—this time, a gathering of holographic trees. High-definition video lends a crisp clarity to the setting of lichen-dusted hills and striated rocks. This terrain is hardly a suitable home for trees, but in Richardson’s world, they appear as apparitions that sway gently in the wind, only to unexpectedly vanish before resurfacing somewhere else.

By definition, The Erudition implies that the audience is witness to an important lesson, but the identity of its teacher and the content of its message are left intriguingly undefined. The eerie scene is accompanied by crackling noises, which sound much like radio static or a skipping record; the soundtrack adds an electroacoustic element that highlights the unnatural aura of the trees’ digital disturbance. It com es as no surprise that Richardson’s work—suggestive of everything from a lunar landscape to a military test-site—is influenced by cinema, especially by futuristic and apocalypse-themed films.

Exploiting the reproducibility of its medium, The Erudition premiered in multiple venues simultaneously: at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery (which commissioned the piece) in its full three-channel version, and at Birch Libralato and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia as The Erudition (I), a single-channel presentation. Richardson’s videos contribute to the rich genre of contemporary Canadian landscape art, adopting a surreal twist that suggests such disparate bedfellows as the trippy paintings of Peter Doig and the seamless digital-composite photographs of Scott McFarland. Despite Richardson’s use of the moving image, her videos dispense with narrative, favouring simple scenarios that draw much of their power from their rich, haunting imagery; a single still from one of her works can capture much of the atmosphere found in the video. Her images tend to linger in the mind. The experience of a Richardson installation, therefore, is often uncanny—it seems that we’ve been here before—heightening the thread of tension that runs through her work.

This is an article from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.