Using the word “collage” to describe Jennifer Murphy’s work oversimplifies it. While the cutting and arranging of images plays a large part in Murphy’s process, she eschews the traditional pictures-on paper approach to collage by installing her constructions directly onto gallery walls. “Twenty Pearls,” Murphy’s first exhibition at Clint Roenisch, demonstrated that her practice has evolved; she handles her materials with a sculptural approach.

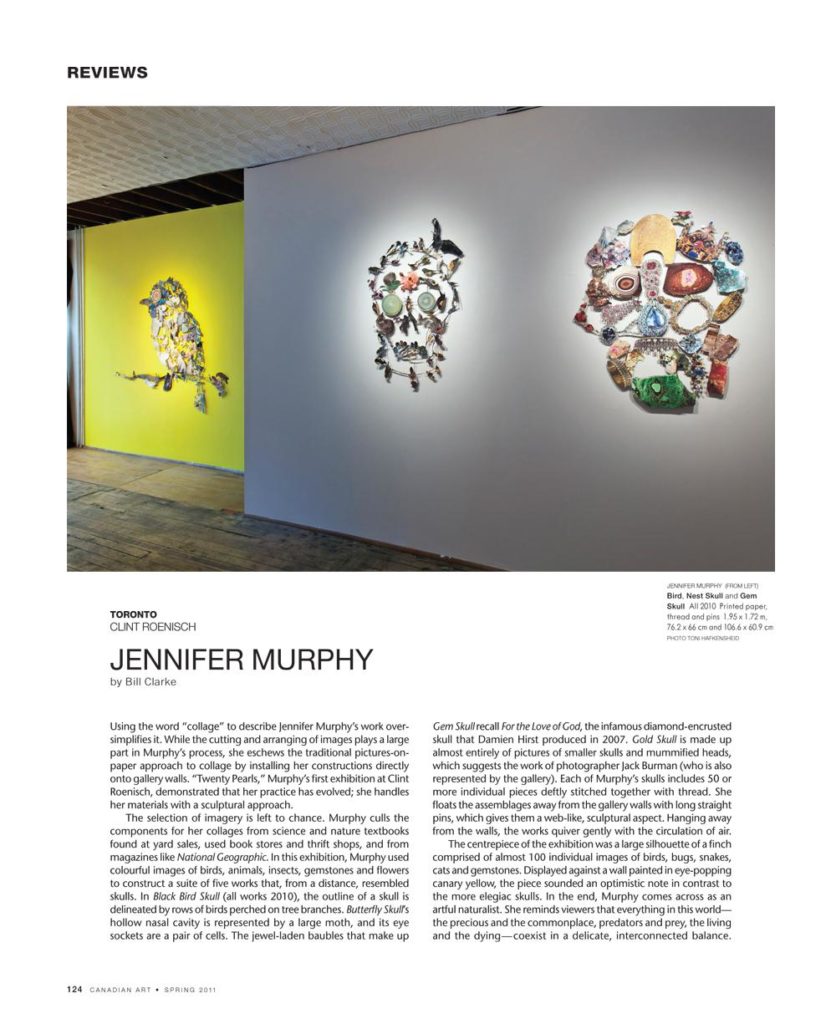

The selection of imagery is left to chance. Murphy culls the components for her collages from science and nature textbooks found at yard sales, used book stores and thrift shops, and from magazines like National Geographic. In this exhibition, Murphy used colourful images of birds, animals, insects, gemstones and flowers to construct a suite of five works that, from a distance, resembled skulls. In Black Bird Skull (all works 2010), the outline of a skull is delineated by rows of birds perched on tree branches. Butterfly Skull’s hollow nasal cavity is represented by a large moth, and its eye sockets are a pair of cells. The jewel-laden baubles that make up Gem Skull recall For the Love of God, the infamous diamond-encrusted skull that Damien Hirst produced in 2007. Gold Skull is made up almost entirely of pictures of smaller skulls and mummified heads, which suggests the work of photographer Jack Burman (who is also represented by the gallery). Each of Murphy’s skulls includes 50 or more individual pieces deftly stitched together with thread. She floats the assemblages away from the gallery walls with long straight pins, which gives them a web-like, sculptural aspect. Hanging away from the walls, the works quiver gently with the circulation of air.

The centrepiece of the exhibition was a large silhouette of a finch comprised of almost 100 individual images of birds, bugs, snakes, cats and gemstones. Displayed against a wall painted in eye-popping canary yellow, the piece sounded an optimistic note in contrast to the more elegiac skulls. In the end, Murphy comes across as an artful naturalist. She reminds viewers that everything in this world— the precious and the commonplace, predators and prey, the living and the dying—coexist in a delicate, interconnected balance.

This is an article from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art