Billed as “the world’s first all-circumpolar, all-night festival of art, music, dance, performance, installation, food and film,” iNuit Blanche took over various venues in St. John’s this past Saturday evening.

From my perspective on the ground, the event succeeded at achieving the playful, whimsical, accessible quality of Nuit Blanche–style events. But, notably and with finesse, it did so without shying away from the realities many Inuit artists and their communities face. Here are nine of my highlights.

1.“Sakkijâjuk”: a group show with intergenerational connections

The exhibition “SakKijâjuk: Art and Craft from Nunatsiavut,” which opened on Saturday at the Rooms, offered a comprehensive point of entry with many of the exhibited artists also participating in events across the city. Curated by Heather Igloliorte, one of the organizers of iNuit Blanche, the show was striking in many ways.

First, it provided a survey of the art of the Inuit in Nunatsiavut (located in Labrador, it’s Canada’s only self-governing Inuit region) the likes of which has never happened in the 67 years since Newfoundland joined confederation.

Second, the structure of the show provided an intergenerational picture of Inuit art in Nunatsiavut. The first section focused specifically on elders, while the final section looked at contemporary practitioners.

Third, due to this intergenerational approach, viewers were introduced to the many ways in which Inuit art of Nunatsiavut is different from that of other Inuit populations in Canada, due to the unique features of the region and the challenges faced by Nunatsiavut’s exclusion from federal jurisdiction.

For instance, the peoples of Nunatsiavut live both above and below treeline, with wood being part of their traditional material culture—and therefore sculptural material too. (An installation of 46 beautifully carved, tiny caribou by Chesley Flowers is a must see.) In contrast, bone and stone are the primary sculptural materials used in Inuit sculpture in Canada.

Also, I was reminded in this exhibition that later generations of Inuit in Nunatsiavut, unlike those proximal to the co-ops and litho studios introduced by James and Alma Houston and Terry Ryan in places like Cape Dorset, have had to move away to advance their artistic practices and find work in their field.

Kemek (boots) displayed to represent five Nunatsiavut communities in “SakKijâjuk: Art and Craft from Nunatsiavut” at the Rooms.

Kemek (boots) displayed to represent five Nunatsiavut communities in “SakKijâjuk: Art and Craft from Nunatsiavut” at the Rooms.

Fourth, craft—like the five pairs of kemek (boots) displayed to represent five Nunatsiavut communities—are included in the exhibition, indicating the way art and craft are intertwined in these and other cultures. Also, informally produced artworks—like Josephina Kalleo’s felt-tip drawings on file folders—further push the breadth of cultural and artistic engagement and recovery of history and identity.

Fifth, and perhaps most importantly, “Sakkijâjuk” continues until January 2017 at the Rooms, providing a touchstone to return to now that the festivities of the one-night iNuit Blanche festival has passed.

2. Throat singing

Adjacent “Sakkijâjuk,” Nain-based photographer Jennie Williams hosted a throat-singing workshop as part of iNuit Blanche, inviting spectators to join her and others in the practice amidst photographs she produced during her residency at the Rooms.

Later that evening, at Wonderbolt Theatre, the Inuit Nunangat Throat Singing Exchange featured singers from different regions trading off in pairs and performing in the round.

Artists Jennie Williams and Tama Ball present an informational session on understanding Inuit throat singing as part of Williams’s Elbow Room residency at the Rooms.

Artists Jennie Williams and Tama Ball present an informational session on understanding Inuit throat singing as part of Williams’s Elbow Room residency at the Rooms.

With the rise of Tanya Tagaq and her Polaris-winning recordings, throat singing is getting more and more of the recognition it deserves across Canada. But seeing it live, in a small group—and having the chance to learn something of the corporeal practice—was a highlight for many attendees at the festival.

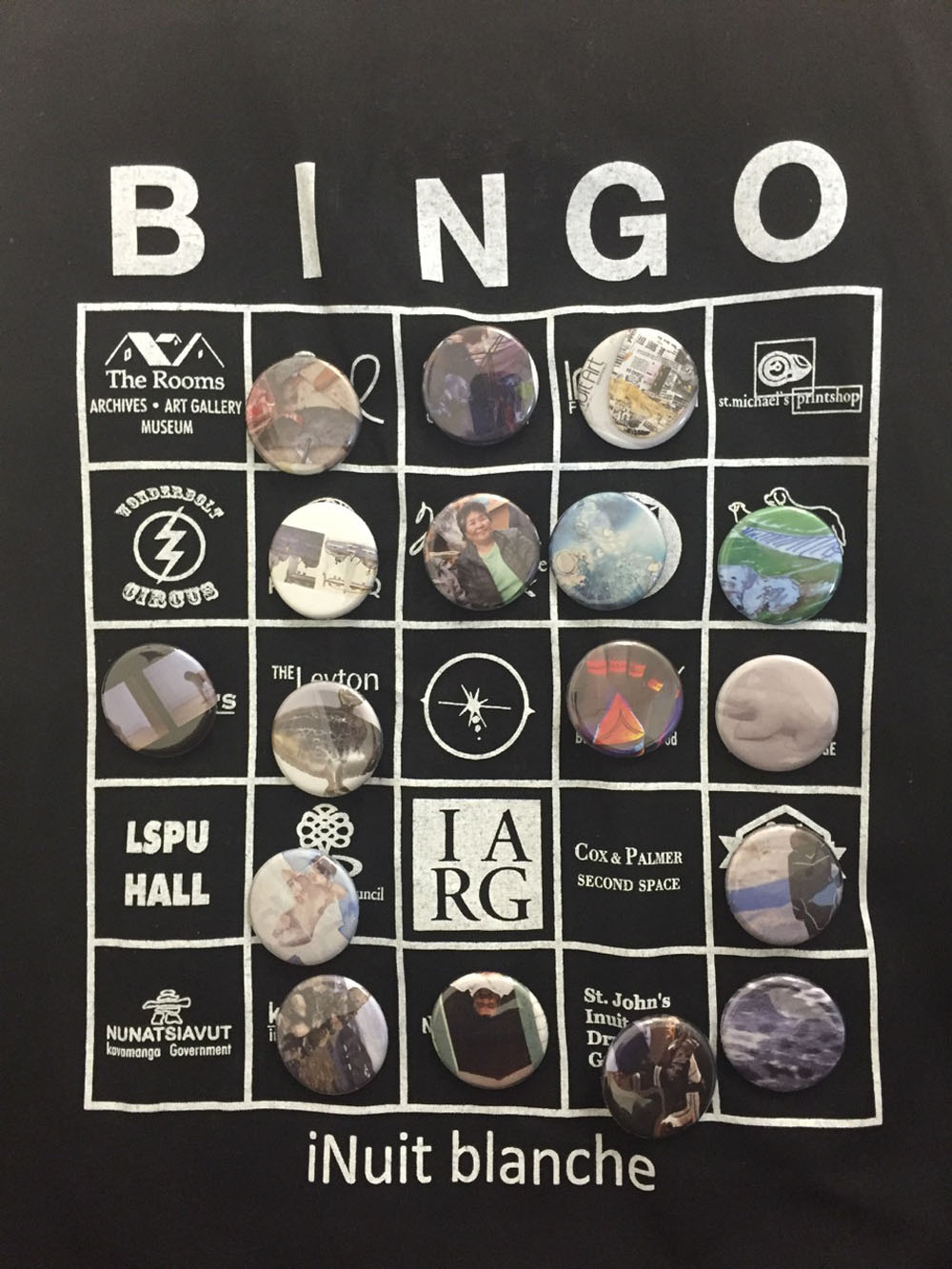

3. Tote-bag bingo

In an ingenious and playful turn on a pastime central to remote communities across the Arctic, the iNuit Blanche tote bag also doubled as a bingo card.

Anyone who filled out a line, or the whole card, was entered to win an artwork by an iNuit Blanche artist.

iNuit Blanche Tote Bag Bingo offered participants the chance to collect artist buttons at each location to win prizes at the end of the night.

iNuit Blanche Tote Bag Bingo offered participants the chance to collect artist buttons at each location to win prizes at the end of the night.

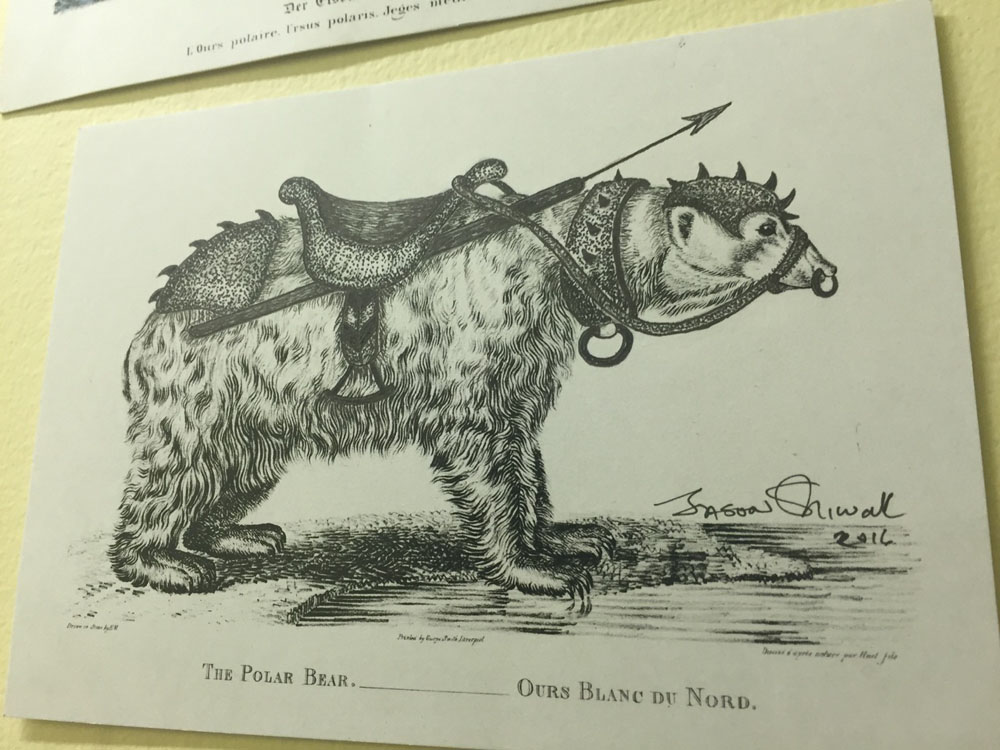

4. Polar-bear cards

People from all over the North responded to colonial imagery of polar bears in the project “Reimagining Nanuq: The Polar Bear Postcard Exchange.”

Presented by the Indigenous Art Research Group of Concordia University, this project invited participants to colour, paint, collage or use any other artistic medium on a collection of postcards based on 19th-century prints of polar bears.

Following the festival, participants were to receive a different postcard artwork in exchange.

Though the postcards were installed quite simply, on a single wall in a hallway, they were kaleidoscopic in their approach in terms of alteration. A good amount of time was spent here absorbing the images—and the related critiques of northern cliches.

5. Arctic char tartare and community-freezer tributes

In a show at Eastern Edge, Barry Pottle installed photo murals about food production in the north alongside Justin Igloliorte’s live performance and serving of Arctic Char Tartare and Labrador spruce-tea cocktails (“country food” with an urban spin).

The performance/meal also underlined how hard it is for an increasingly urban Inuit population to access traditional food, and thereby traditional culture.

An altered postcard in “Reimagining Nanuq: The Polar Bear Postcard Exchange Project.”

An altered postcard in “Reimagining Nanuq: The Polar Bear Postcard Exchange Project.”

6. Tanya Lukin Linklater’s Slay All Day

Slay All Day, a two-screen video work by Tanya Lukin Linklater, had its public-screen debut at iNuit Blanche following its initial premiere earlier this year on the Remai Modern’s website.

Screened on the side of 72 Harbour Drive, the video was typically Nuit Blanche-ish in its presentation (large public projection) but unique in its content: in the four-minute film, Linklater performs a series of movements and gestures informed by Inuit athletics, as well as Robert Flaherty’s film Nanook of the North.

7.“Sakkijâjuk”’s opportunity to bear witness

Among the works created by the youngest generation in “Sakkijâjuk,” one carving by Davidee Ningeok is particularly haunting, depicting an instance of corporal punishment from a residential school.

Jacko Pijosse is another younger artist featured in the final section of “Sakkijâjuk.” As his biography indicates, he was born in Nain in 1994 and died by suicide while the exhibition was being put together. Pijosse’s inclusion serves as a loving tribute, and a reminder of the stark realities faced by the communities in Nanutsiavut and the challenges ahead for the self-governing region.

Barry Pottle presents his contribution to “Community Freezer,” a collaboration with chef Justin Igloliorte.

Barry Pottle presents his contribution to “Community Freezer,” a collaboration with chef Justin Igloliorte.

8. Joar Nango’s Nomads Won’t Sit Still for Their Portraits

Proving the “all-circumpolar” scope of iNuit Blanche, a film by Sami-descended, Tromsø-based artist Joar Nango was screened.

Nomads Won’t Sit Still for Their Portraits (2015) is a dreamlike narrative portrait of nomadic life in urban Mongolia, as well as an exploration of how certain materials—like the thick felt used in yurts—make that life and culture possible.

Nango also placed pieces of felt on the floor of the darkened room where the video was projected, and an ambient soundscape clashed with a mock-anthropological voiceover, creating connections between multivalent approaches to nomadic cultures in the 21st century.

9. Heather Campbell’s climate-change painting

Heather Campbell’s watercolour painting of a scene where Inuit settlements have adjusted to climate change has stayed with me since I left St. John’s.

In the painting, spherical pods reminiscent of igloos—nestled in a new, greener, vegetated north—provide housing, while electricity-generating windmills stand nearby. A geodesic dome looms in the distance.

Utopian, or at least optimistic, in flavour, the image mirrored the dynamism and adaptation that has come to define many Inuit experiences in contemporary Canada.

Live painting workshops with Heather Campbell were another aspect of iNuit Blanche.

Live painting workshops with Heather Campbell were another aspect of iNuit Blanche.

A clarification was made to this article on October 20, 2016. The original article failed to mention Terry Ryan and Alma Houston, who were, among others like James Houston, also important in the development of the West Baffin Co-op, as detailed on the Dorset Fine Arts website.

Chesley Flowers, The George River Herd, 1995–96. Wood and antler. 121.92 x 121.92 cm. The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, Memorial University Collection.

Chesley Flowers, The George River Herd, 1995–96. Wood and antler. 121.92 x 121.92 cm. The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, Memorial University Collection.