The word “instigators” is rarely used to describe Canadians. Being brash, audacious and provocative seems alien to the Canadian psyche: we specialize in playing it safe. Can we seriously believe the title of a group show of senior and mid-career Canadian artists called “Instigator(s)”?

The historical development of Canadian art and how the public engages with it would seem to argue the contrary. The rise of 1970s nationalism insisted on the canonization of the Group of Seven as “official” Canadian culture, to the exclusion of any other art or artists. While they had long dominated galleries nationally and their members had been influential teachers in our art-educational institutions, the group spawned a lucrative commercial industry during these years. Mass reproductions and merchandising sales made them ubiquitous in the lives of Canadians. A parallel development can be seen in Quebec with the Automatiste artists. They had long lost their revolutionary status and were institutionalized by the Quebec establishment. In this way, painting became enshrined as the dominant discourse in Canadian art.

The valorization of these artists, whose sensibilities were imported from Europe and New York City, encouraged a producer/consumer hierarchy in the creation and appreciation of art. These artists became stars in Canada, their lives were romanticized, and so too was their art. Modernist ideology championed “inspiration” and a somewhat magical sense to the act of creation. Art was seen as “timeless,” ready to take its place alongside other great works of art. These attitudes reinforced the perception of art as a commodity.

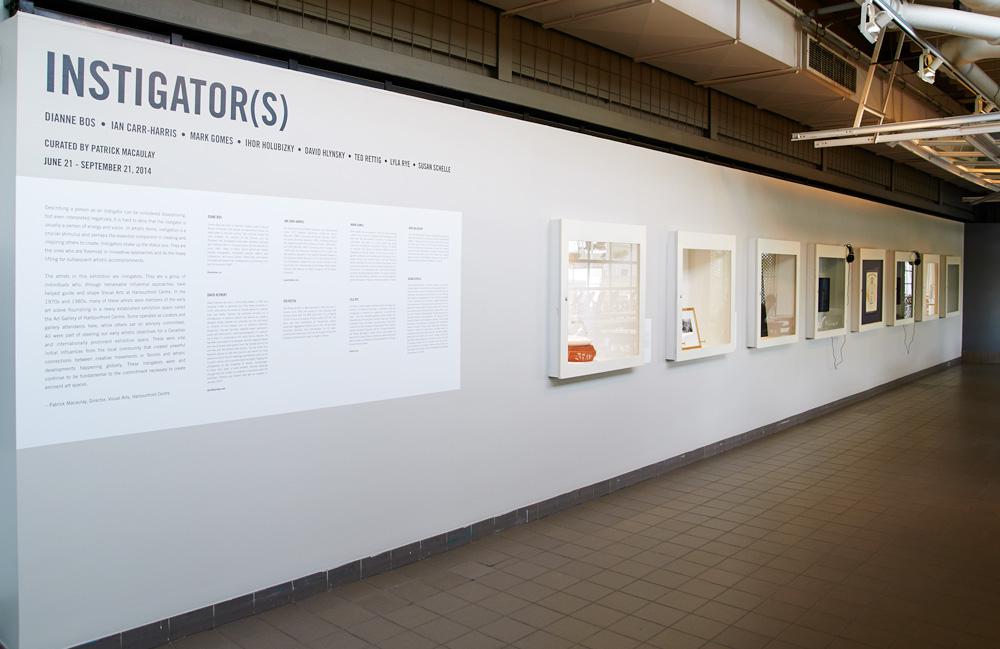

“Instigator(s),” a vitrine-based show which recently closed at Harbourfront Centre, argued a counterpoint to this development, featuring artists not interested in making “safe” art or catering to the rigid demands of mass consumerism. These artists—Dianne Bos, Ian Carr-Harris, Mark Gomes, Ihor Holubizky, David Hlynsky, Ted Rettig, Lyla Rye, and Susan Schelle—encourage critical thinking, emphasizing art as a constructed artifact, strongly situated in place and the everyday.

All the artists in “Instigator(s)” were also involved in developing what was known as the Art Gallery at Harbourfront in the 1970s and 1980s. As curators, committee members and gallery attendants, these artists articulated the objectives of a developing exhibition space that featured emerging avant-garde practices such as sculpture/installation and new media. Curator Patrick Macaulay uses the term “instigator(s)” because the artists in the show can be seen as provocateurs of the local scene who encouraged area artists, refusing the status quo to be supportive of (and to push for) a distinct Toronto voice.

In his series Euclid, Ian Carr-Harris duplicates the childhood blackboard and cursive writing from elementary school. He turns the ordinary into the extraordinary: emphasizing the world is now “read” as a world of text. The work questions the nature of drawing and the relation between word and image, as well as the physical “presence” of the art object. This is also the discourse of the classroom and education, power and authority, and we are reminded nothing is as commodified as knowledge is in Western society. The perfectly written letters and chalk-drawn lines on the blackboard remind me of the book A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man when James Joyce’s alter ego Stephen Dedalus realizes the power imbalance between the words he speaks and the words spoken by his teacher.

Minimalism is a mainstay of the avant-garde that reduces art down to its essential form, making something “new” while borrowing from the past. Dianne Bos has long explored the anti-technology appeal of pinhole photography in today’s digital world. While mining the historical origins of photography, Bos’s conceptual concerns elevate her work far beyond 19th-century photographic aesthetics. In her piece made for this exhibition, Ptolemy’s universe chart is depicted with a small hole in the centre, structurally recalling a pinhole camera. Like Galileo peering through his telescope to see new worlds, the viewer looks through the hole to see a street map of Toronto which highlights where the viewer is standing—in the case of “Instigator(s),” at Harbourfront Centre. In this coy and playful work, scientific inquiry and the cosmos give way to an investigation of place, producing an effect akin to looking through the reverse end of a telescope.

Installation artist Lyla Rye also revisits the origins of her medium in two works that reinterpret Buster Keaton’s 1921 film The Haunted House. In The House Haunted, Rye maintains the integrity of the silent film original, complete with placards, a chase scene and slapstick comedy. Through her interest in architecture and through the use of multiple screens, Rye encourages the viewer to see the film as a constructed artifact; it moves from scene to scene, mapping its way through the house. In her more sinister video Spectregraph, Rye positions the staircase of the original film as a central image and uses current video technology to manipulate the surroundings—repeating and overlaying the action, inverting colour, and manipulating the original length of each scene. Recurring ghost images evoke the mainstream cinema of the past and the legacy of avant-garde filmmaking.

“Instigator(s)” was faithful to the original mandate of the Harbourfront exhibition space and its legacy of encouraging artistic practices beyond the commercial gallery system. Not content to rest in the past, the conceptual art it featured is rigorously intellectual in its exploring modes of inquiry into other philosophical disciplines: Carr-Harris and geometry, Bos and astronomy, and Rye and architecture. Macaulay wisely chose artists who use wit and playfulness to engage the public in questioning the art subject. This show included work that should be fundamental to an art education, art that signifies its own construction and the materiality of art discourse. While the appropriated historical discourses evoked the past and the origins of the Harbourfront venue, this show felt very much alive in the present. These instigators try to take Canadians out of their comfort zone. Their oeuvre is not the art of passivity; it is an art of ideas and possibilities.