Caroline Monnet’s recent solo exhibition “Like Ships in the Night,” curated by Peta Rake at Banff’s Walter Phillips Gallery, feels like being cradled by the ocean. Loud, rhythmic sounds fill the dimly lit room with dramatic crescendos and decrescendos. Water pushes at you from all around, submerging you under the Atlantic.

Projected nearly ten meters wide onto the entire back wall is Transatlantic (2018), a 15-minute Mini DV video, that collects footage from the artist’s voyage across this ocean. The video’s split-screen images patiently pull you from one continent to the other—sailing by massive piles of sand, windmills and smoke-billowing factories at the Dutch port of Ijmuiden, out onto the open sea and finally through the Saint-Lawrence to Cleveland. From the point-of-view of the deck of the cargo ship comes expansive sky, then calm horizon punctured by giant waves in foamy white tumults. In the gallery space, across from Transatlantic, just beyond the gallery doors, is Bridging Distance (2018), a vinyl reproduction of a still from the video that is even larger than the screen at nearly 13 meters wide and 4 meters high. Blue-grey ocean water fills the scope of your vision.

When she started making the show, Monnet was thinking about culture. “I felt like the Atlantic ocean was acting as a middle ground for both sides of my ancestors to meet,” she says. Monnet has both French and Algonquin heritage. She feels connected to both, but also has mixed feelings about the settler-colonial state of Quebec and Canada. “If we’re starting to talk about culture and identity and lack of communication between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people—often culture and language will be at the root of any conflict around the world. I was interested in exploring other ways of communication that would be universal, where we could actually get to a common understanding”

A variety of non-human life forms have unique ways of communicating. Underwater, for example, sperm whales, reminiscent of Melville’s famous Moby-Dick, make clicking sounds that beam out in massive sound waves. When sperm whales perceive these sound waves bouncing off objects in their perimeters, they are able to gauge how to navigate. When they communicate with one another, rather than “hearing” in the way we understand it, the sound waves’ vibrations don’t just hit their ears but rather push up against their massive heads to create a reverberation that allows them to feel what is being communicated to them by other whales.

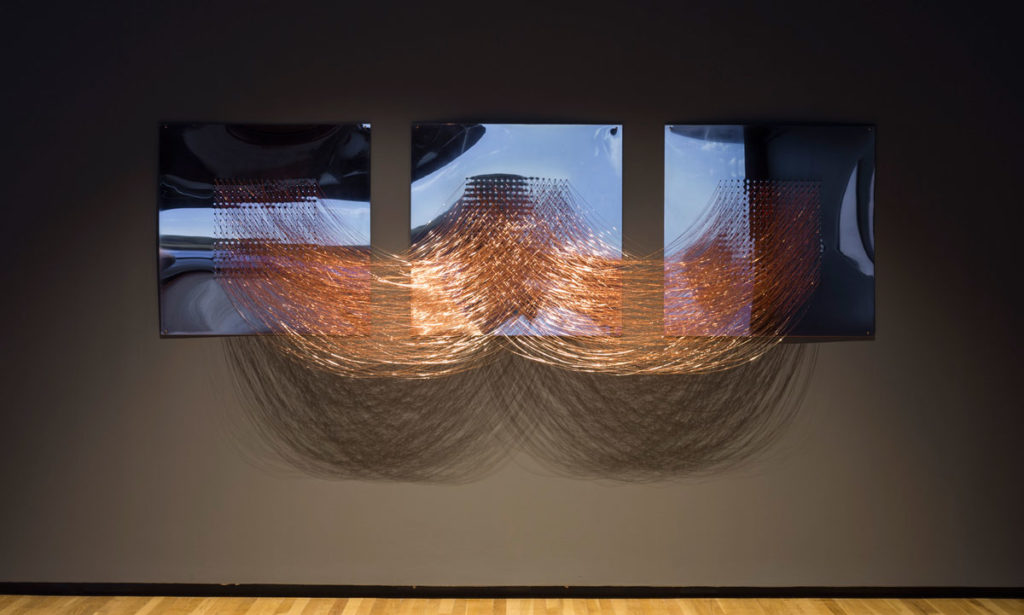

Installation view of Caroline Monnet’s Semaphore I, II, III (2018) at the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rita Taylor.

Installation view of Caroline Monnet’s Semaphore I, II, III (2018) at the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rita Taylor.

The tensions Caroline Monnet wants to get at among culture, communication and language come to a similar head in the exhibition’s forms. She gave the sound artist Simon Guibord, who created the soundtrack, instructions to experiment with morse code and radio waves. “The entire show is about communication, or lack of communication,” she explains. Guibord’s soundscape swells and ebbs as the moving images of the video transition back and forth between the abstracted chaos of a torrential sea and the clean representation of a calm horizon.

In other pieces the simplicity of Monnet’s forms maintain a link to different cultures and languages. The three frames of Semaphore I, II, III (2018), collaged from a video still, are all at an angle. The white peaks look like flags atop a mast, evoking the horizon in several ways. “Semiphores are a specific language used mostly on boats during war time to convey messages across large distance,” she says. “It’s like talking with flags, basically.” The future itself has a future (2018) consists of three copper plates connected by tiny wires in organized multiplicity. Here copper, a mineral closely tied to Algonquin culture, is stretched into thin wires like the unwieldy telephone cables strung across the ocean floor that for a long time formed the basis of telecommunications networks.

In addition to being closely ensconced in the elements of Monnet’s exhibition, I felt like everything in it was on the brink of something major. The large balls of Proximal I, II, III, IV, V (2018), jarring in their presence, are spread across the floor. The huge, perfectly round cement balls rest atop oil-black plinths, and seem to threaten to roll towards you, like boulders on a cliff. Yet they hold their stillness. Everything demands the viewer’s utmost, sharp attention and in this way the exhibition grounds the body. This dead calm could just be the eye of the storm.

Installation view of Caroline Monnet’s The future itself has a future (2018) at the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rita Taylor.

Installation view of Caroline Monnet’s The future itself has a future (2018) at the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rita Taylor.

Ultimately, the full effect of “Like Ships in the Night” is quite emotional. Due to the tension in Monnet’s show between communication and abstraction, meaning is not always easily deciphered. Rather, you feel everything before understanding it. For Monnet, “It’s about boiling things down to the bare minimum or to the essence of that feeling.” This embodied communication can do just as much as any explanation with language or clear form sets.

This exhibition marks a shift in Monnet’s practice: previously the artist has mostly made films. She is a member of ITWÉ, the Aboriginal digital-arts collective, and was selected for the Cinéfondation Cannes Film Festival Residency in 2016-2017. Though she is now working on her first feature-length film, what she is able to articulate in this show achieves something on par with the sperm whale’s somatic way of intuiting the world. Sometimes, what an artist conveys can only be deciphered by the body.

Caroline Monnet’s “Like Ships in the Night” debuted January 26 to May 6, 2018 at Walter Phillips Gallery and is on view at the 4th edition of the International Digital Art Biennial (BIAN) from June 29 to August 05, 2018 at Arsenal art contemporain in Montreal. Monnet’s work is also featured in the “Conflicting Heroes” group exhibition at Art Mûr Berlin from June 8 to August 4, 2018 as part of the Contemporary Native Art Biennial (BACA).