While historians continue to struggle with what to call the first and second decades of the 21st century, art historians have it doubly hard. Never mind this obsession with naming these decades—what are, and were, its -isms?

One way to approach these questions is to set them aside for a moment to consider first the displacement of hard-copy forms that, until our present century, supplied us with the bulk of our music, pictures and literature, and how the re-spatialization of these mediums (via a largely invisible delivery system) is consistent with a time that can be neither named nor reduced to singular movements.

With that in mind, what does it mean to produce or consume a CD, a DVD or a glue-and-paper book when the music, pictures and literature they contain are now more commonly produced and consumed through one’s phone? Is it both a political and an aesthetic act to continue with these apparently obsolete forms, as it was in the 1980s when the digitization and increased corporatization of the music industry resulted in multi-track tape decks showing up at thrift stores, where they were purchased and put to use by musicians associated with the North American “lo-fi” indie movement? Are we now at a similar place with the hard-copy book?

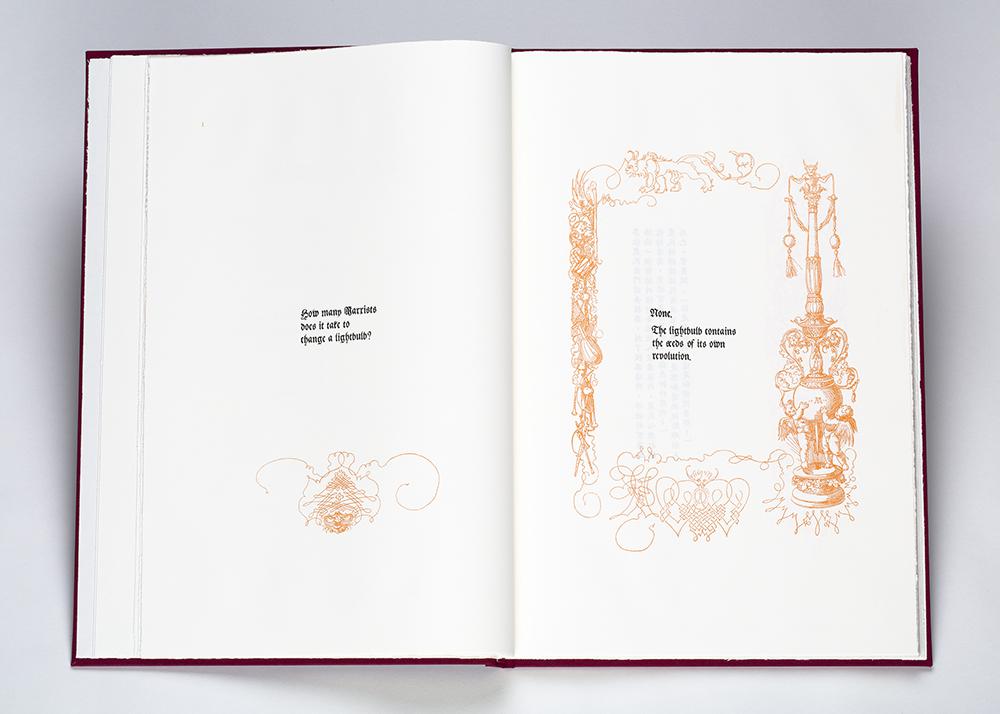

Hyung-Min Yoon‘s current exhibition at Grunt Gallery, “The Book of Jests,” was inspired by a 1922 edition of a book she purchased at an antiquarian bookstore in Vienna. The book—entitled Marginal Drawings for the Prayer of Maximilian I by Albrecht Dürer—contains within it a series of illustrated pages whose blank centres were originally designed to house translations of a single Christian prayer. As artist Lorna Brown remarks in her exhibition essay, “For an artist whose work has explored the ‘imperfect path’ of translation, the interpretation of images across cultural contexts, and the history of printed text, this central unmarked ground must have seemed an almost overwhelming space of possibility.”

Spurred on by this “space of possibility,” Yoon constructed a book whose pages contain within their “unmarked ground” (defined, as it were, by Dürer’s original drawings of soldiers, beasts, columns and curlicues) political jokes in languages that include Arabic, Czech, Hebrew, Mandarin and her native Korean. Although it is not likely that a single viewer of this work will be familiar with more than three or four of these languages, Brown mentions that the jokes Yoon selected (rendered in a font from Dürer’s era) were placed in their respective spaces in relation to the illustrations, thus providing new meanings that speak to a world united not by a single prayer, as Dürer was commissioned to illustrate in 1515, but by the contradictions of 21st-century global capital.

To the question of how to display an art object in a setting where turning its pages threatens its future legibility, Yoon printed a separate set of pages, seven of which hang in frames from the walls that surround this book, which is opened to its middle section and encased in a vitrine. But if that is not enough, viewers are directed to the gallery’s media lab, where a video plays of the artist’s hand as it turns the book’s pages, pausing for those who, if they are familiar with these languages, have time to read them and, once again, consider them in relation to their respective illustrations (or if they do not understand these languages, read their English subtitles).

Among the questions often asked of the future of the hard-copy book, the most common concerns its necessity in the age of digital production and distribution. An equally common response has it that the hard-copy book is a haptic affair, that holding it in one’s hands is as important to the reading experience as what it says inside and outside its covers. Another relates to the impossibility of reproducing the relationship between the traditional book’s inks and papers, particularly those made by its authors (which might explain the renewed interest in artist books), much like a painting needs to be seen as it was made, not as it is transmitted through electricity and plastic.

Prior to Dürer, a similar argument was made with the invention of the printing press, when religious texts were the domain of clerics entrusted by their temples and churches to interpret them, as an actor would a script (or scriptures). In making these texts available to those who, with the rise of literacy, could read and debate their meanings, it was the middle man who became redundant, while the book, available to readers in the privacy of their own home (and without digital surveillance bots), prospered for the remainder of the second millennium.