The Ryerson Image Centre may be mandated to focus on the visual, but you will hear the boom of Martin Luther King Jr.’s voice echo through the gallery several times during a visit to the exhibition “Human Rights Human Wrongs.”

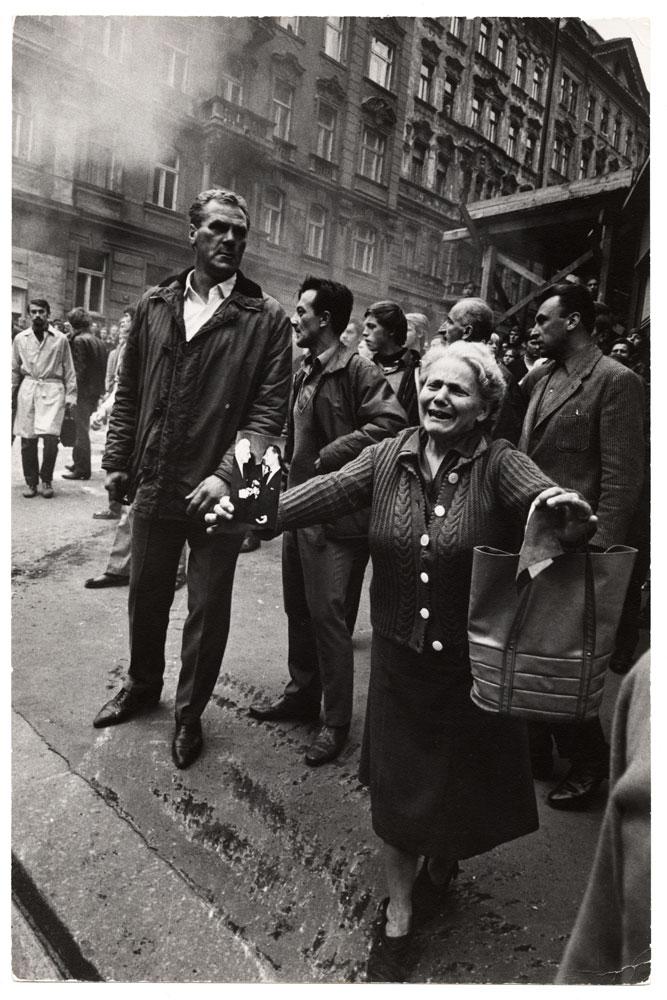

The audio accompanies more than 300 disturbing and poignant photographs of political and social struggles, mainly taken in the latter half of the 20th century and drawn from the RIC’s Black Star collection of news photographs.

Curated by Autograph ABP director Mark Sealy, who is focused on the representation of identity politics, human rights, and violence in photography, “Human Rights Human Wrongs” demonstrates sensitivity towards the power hierarchies that inform representation.

The exhibition investigates photography as a beholder and agent of change, recognizing that while photographs are indices of reality, they are not neutral. Photographs represent a perception of a particular reality and thus, photographs can both sanctify and undermine humanitarian objectives.

At first, Sealy’s chosen methods of display—tightly crammed photographs and limited wall text—seem to beg the viewer to revert to the usual processes of consuming tragedy: scan the photograph, imbue it with an easy dichotomy of good and evil, and move on.

It is this facile consumption of human-rights struggles that the exhibition seeks to subvert—and ultimately succeeds in this subversion. Thanks to skillful positioning by Sealy, each photograph is obliged to engage in a dialogue with its neighbor; in this way, the crammed display format becomes a means not of passive viewing, but of active exchange.

For instance, Japan Cruelties, dated 1904/1905 and by UK photojournalist Jimmy Hare, shows a Chinese prisoner being tortured by a Japanese soldier. The photo’s caption inscription denounces the “sadistic” nature of the Japanese army. Beside it hangs Rhodesia, dated 1896 and by an unknown photographer. This shows rebels of the Matabele nation who have been captured by British South Africa Company troops. Through the clever arrangement of these photographs, the “savage other” is revealed in the Western “self.”

Another refreshing pairing: François Sully’s photograph Vietnam. North Vietnamese, circa 1963, showing Vietnamese female soldiers saluting, and David Rubinger’s photograph of Israeli female soldiers marching in the street in 1963. Contrary to the typical visual culture of war, nationalism and the force of the military are personified in these images by the female (rather than male) body.

It is certainly interesting, and at times uncanny, to view these photographs with the luxury of 21st-century hindsight. Images of fallen soldiers and civil unrest in colonial Tunisia and Morocco seem like they could have been taken yesterday elsewhere in the Middle East. Indeed, the idea of interconnectedness between different human-rights struggles is emphasized in this show as take-away cards in the exhibit highlight certain photographs and their temporal relationship to other human-rights violations and achievements.

As you walk through the exhibition, you come to realize that the photographer’s role in documenting struggle and conflict is both as a witness and as a bystander. These photographers are the Weegees of human rights.

For instance, in one of the first images of the exhibit, Poland WWII, Warsaw (circa 1940, by an unknown photographer), we see an emaciated corpse lying on the street, with passersby seemingly aloof. Montgomery by Charles Moore, taken around 1960, shows white men about to beat two African American women; others in the background simply observe, some in terror and others with sly smirks. Several of the other photographs on display show people in the final moments of their lives.

Given the intensity of such images, questions emerge: What is the role of the photographer in capturing such images? Is photography a form of activism or objective reportage? Does the photographer have a responsibility to intervene? You are urged to decide on your own.

One of the more striking images of the exhibit, an untitled shot taken in 1967 Vietnam by Max Scheler, shows a soldier lounging with a Vietnamese woman while she gazes out remotely in quiet contemplation. Looking at this image, I was reminded of 19th-century Orientalist paintings of women in the harem or the baths—images in which “exotic,” languid women are presented for the pleasure of Western males. This photograph seemed to capture that imagistic power dynamic playing out in real life.

“Human Rights Human Wrongs” certainly injects our Third-World-tragedy voyeurism with critical thinking. The exhibit is more about what photographs say in relation and in opposition to each other, rather than how they act as historical records.