I’ve been thinking a lot lately about environments that are both calming and overstimulating, both specific and immersive. Partly this is because I’ve been curating a show of a few artists who use that strategy. And partly it is because there are a few other exhibitions on right now in Halifax that have this effect. In particular, in their solo exhibitions across the city, Tove Storch, Angela Henderson and Juss Heinsalu have created pared-down, immersive environments each focused on a single material: steel, concrete or clay.

Storch’s sculptural work is most often translucent. The Danish artist creates fragile barriers of stretched matte silk or rubber, and she tests fabrics like “see-through black cloth scraped with transparent silicone” until they’re unrecognizable. For the most part, her works rarely include firm, classic sculptural materials. In 2013 she claimed, “It gives them some kind of distance to the usual rules of space as something solid.”

Tove Storch, Untitled 2017 (installation view at MSVU Art Gallery), 2017. Photo: Steve Farmer.

Tove Storch, Untitled 2017 (installation view at MSVU Art Gallery), 2017. Photo: Steve Farmer.

Storch has turned her attention towards steel for her exhibition at Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, which is on view until April 9, making a material departure from her past work. A forest of hand-bent steel rods fill the gallery, each oxidized with a thin layer of rust, spanning the distance from the floor to the ceiling. They scribble through the open space, rendering the expansive gallery two-dimensional. The natural light from the second-storey windows casts only minimal shadows, robbing the installation of any three-dimensional depth. Storch maintains her interest in translucency by drawing the eye through the material, simulating lightness and flexibility through the use of steel.

The exhibition does not shy away from the word minimalism, a theme being embraced by multiple artists and arts institutions in the Atlantic.

Angela Henderson, New Work – Secrets save me from dissolving, 2017. Courtesy Hermes Gallery. Photo: Steve Farmer.

Angela Henderson, New Work – Secrets save me from dissolving, 2017. Courtesy Hermes Gallery. Photo: Steve Farmer.

Henderson’s new works in cast concrete are witty, subtly destabilizing the male-dominated history of Minimalism. Unlike the immense works of the Minimalist era that showcased the heroic raw power of their creator—bad boy Richard Serra comes to mind, violently throwing thousands of pounds of molten lead indoors—Henderson relinquishes control over her material experimentation. She calls this work a feminist gesture within Minimalist visual language, one which embraces the opportunity for failure and instability.

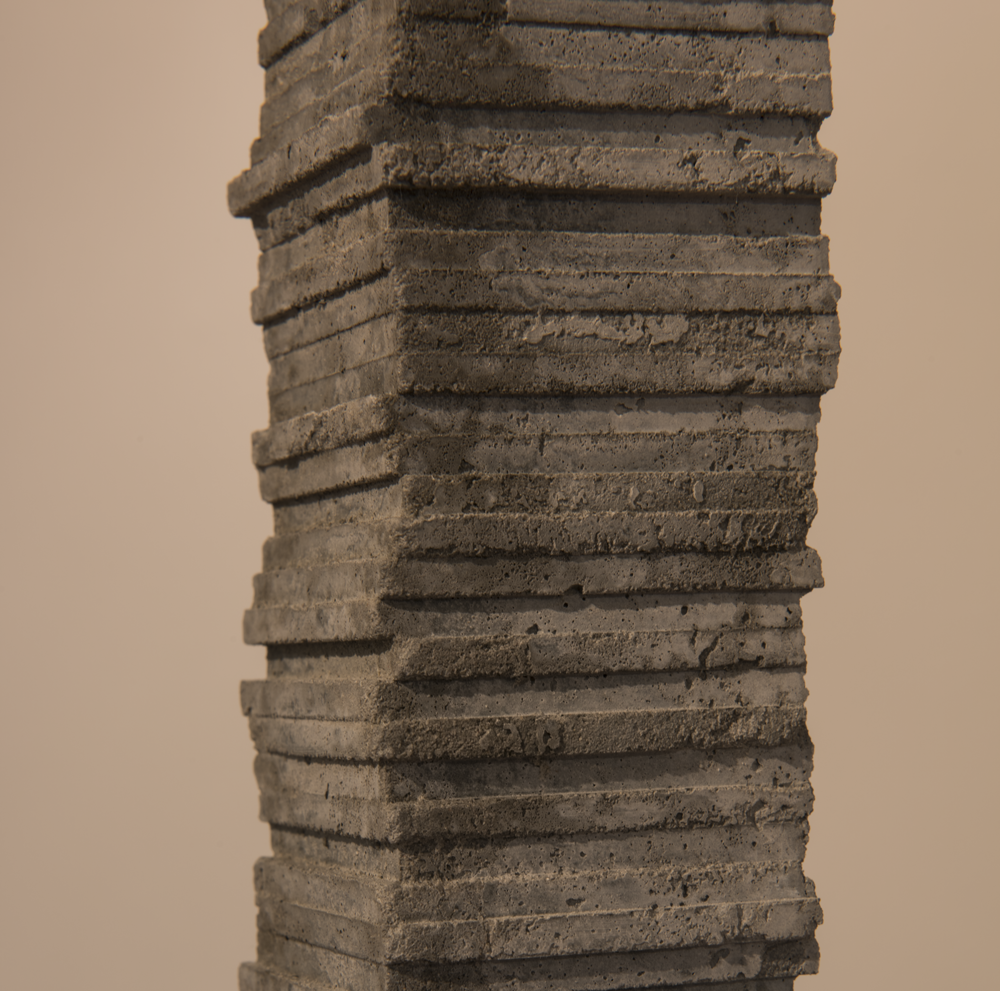

The exhibition features six thin, cast-concrete pillars anchored to the low ceiling of Hermes Gallery, each hovering above knee-height. Each of the forms is striated with hundreds of thin layers that were individually cast using Plexiglas moulds. She characterizes the work as anti-monumental, marked by cracks and the potential for erosion.

Borrowing its title from Anne Carson’s Decreation, Henderson’s exhibition “Secrets save me from dissolving” is a part of its own destruction. It is slowly getting both stronger and weaker—the concrete itself hardens and cures with time, but the structure decays in response to its changing environment. As Henderson released the layers from the moulds, they would chip and self-destruct, cutting her hands and recording her fingerprints. Countering the Minimalist impulse to erase all traces of authorship to favour clean, impartial objects, Henderson uses the pliable material to document her impulses.

Juss Heinsalu, earth-sky (detail), 2016. On view at the Anna Leonowens Gallery.

Juss Heinsalu, earth-sky (detail), 2016. On view at the Anna Leonowens Gallery.

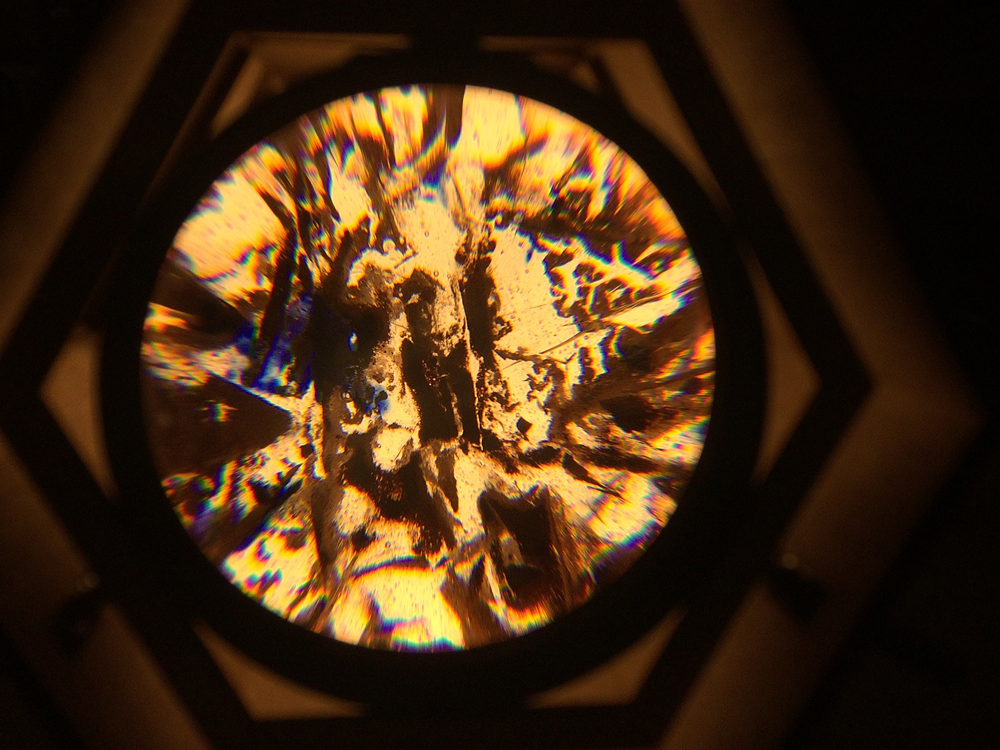

Heinsalu’s MFA exhibition “savi|skoop” is a scientific investigation into the optical properties of clay. Three elements light the pitch-black Anna Leonowens Gallery: a clay lightbox, a ceramic-lens projection and a Galilean telescope which magnifies a fired clay slide.

In from earth to sky, a handcrafted projector throws light through a clay lens, projecting a hazy image onto a monumental hexagonal projection screen. Contrasting in scale, the miniscule eyepiece of claydoscope—a downward-facing telescope—reveals a clay lens that warps downwards at the edges, not unlike the refraction that occurs on the horizon. As the eye adjusts to the eyepiece, blue “fringing” appears around the dark cracks in the clay sample, creating the illusion of movement. This optical distortion occurs when lenses are not perfectly aligned to the same convergence point, a subtle reminder that Heinsalu’s telescope was meticulously crafted by hand.

In “savi|skoop,” clay becomes virtually unrecognizable. Heinsalu has processed the material to a point where it is released from its cultural and social ties, without becoming devoid of meaning. For the Estonian artist, the cracks and ripples that form in the firing process become signifiers of natural laws, and, in this way, he says, “inanimate materials actually embody life.” What is captivating about “savi|skoop” is that it focuses on clay, but the exhibition is not about clay. Through a process that is almost alchemical, Heinsalu transfigures material and allows it to transcend the societal expectations imposed upon it.

My ambition as curator for “Sound Etiquette,” produced by Centre for Art Tapes, and hosted at Khyber Centre for the Arts until April 24, was similar: to highlight works that manipulate language and release it from the coded social norms that confine it. In particular, I wanted to make room for illegibility, fighting against the expectation that language should be comprehensible and linear.

For instance, Sonia Boyce’s Exquisite Cacophony is aptly named. The 35-minute video documents a performance between a freestyle rapper and a classically trained vocalist, and it fills a gallery space with rapid-fire banter, bird calls, slam poetry and synchronized breathing. When I started the initial planning for an exhibition of artworks that break the rules of sonic communication, the piece—which broke through to wide acclaim at the 2015 Venice Biennale—was an obvious choice. I find it pleasantly overstimulating—it’s the opposite of sensory deprivation, yet it yields a similar impact by blocking out all external stimuli.

Although there is nothing minimalist about “Sound Etiquette”—the space is consumed by gold text, noise, song and closed-captioning, and includes works by Christine Sun Kim (originator of the titular term) and Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay as well—it aspires to generate the same kind of immersive environment that Storch, Henderson and Heinsalu have created.

Amanda Shore is a writer and curator based in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She works for the Association of Artist-Run Centres from the Atlantic as programming coordinator for Flotilla/Flottille, a biennial gathering of artist-run centres that will take place in Charlottetown in September 2017.

“Sound Etiquette” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy the Khyber Centre for the Arts and Centre for Art Tapes.

“Sound Etiquette” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy the Khyber Centre for the Arts and Centre for Art Tapes.