When Gordon Rayner died suddenly at 75 of a heart attack in his Toronto home on September 26, 2010, he was two weeks shy of unveiling an exhibition at Christopher Cutts Gallery.

While Rayner was a towering figure in the Canadian art scene through the 1980s, best known for his muscular, sensuous and often unabashedly ravishing landscapes that channel both the Group of Seven and the abstractions of Jack Bush and the Painters Eleven, by the time of his death Rayner was a much less prominent figure: his primal, physically immediate approach to painting and his lavish use of colour had largely gone out of fashion, and he had increasingly withdrawn from Toronto, whether north to Magnetawan or south to Mexico.

Yet Rayner’s late work, flawless in its mastery and restlessly inventive in its technique, includes some of his finest.

Like Courbet’s great seascapes, Rayner’s landscapes are less about the picturesque—nature tamed to a human scale—than about natural forces.

In the stunning Big Blue Sky Falls (2008), which was part of his 2009 exhibition at Christopher Cutts, “Rapids, Falls and Dark Waters,” white-streaked blue water, interspersed with bands of black, roils down over boulders toward the picture’s lower edge, a twilit blue forest behind. Big Blue Sky Falls, despite its ecstatic title, has a dark, brooding tone, as though these falls were crashing through the unconscious.

Sweet Fall, Falls (2007), by contrast, is sumptuously autumnal, the boil of whitewater pouring down a steep cliff, conflagrations of red and yellow encroaching from one side, the water eventually swirling into a deep blue pool at the bottom of the painting: this is autumn not as melancholy decay, but as the final and definitive expression of summer.

And in Maple River, B.C. (2008), the swift water shifts between velvety purple, mineral green and drifting sheaths of foam white as it descends between two rock formations, one in deep shadow, the other in soft, warm evening sunlight. In these paintings, Rayner used a mix of oil, acrylic, and collage to great effect, the tensions between the materials mimicking the constant motion of the landscape itself.

The paintings in “The Oaxaca Suite,” recently closed at Christopher Cutts, were largely executed in a ramshackle colonial villa Rayner lived in in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, in a burst of creativity between October 1993 and June 1994. While works like those featured in “Rapids, Falls and Dark Waters” are very much part of a Canadian sublime in which the wild force of nature—all that churning, beautiful, indefinable water—dwarfs anything like human agency, the paintings Rayner did in Oaxaca, all in bright, high-keyed acrylic, are at the intersection of the dumpily human and the unsettling, and archaic, divine.

Warrior Dancer (1993), the first painting in the series, has a man wearing a deer head, holding a rifle and sitting on a giant green frog; behind him on the wall is a mirror (or perhaps a window) full of cloud-streaked blue sky. Whatever battle this warrior is about to embark on, it is surely one that involves the spirit world.

At the centre of The Dogs of Oaxaca (1993) is a dog wearing a menacing, pre-Columbian mask, his tongue lolling out, while around him other hounds doze and frolic and scrap, all of it set against a blue ground swarming with patterns of white dots, the green vapour trail of a comet streaking down toward the lower edge of the canvas: these are, apparently, celestial dogs.

Indeed, dogs, frogs, goats, and Rayner himself drifted through the paintings of “The Oaxaca Suite.”

In The Empty Church (1994), for instance, two dogs spar in front of a blood-spattered, flower-wreathed shrine with a doll-like baby Jesus making the traditional gesture of peace; behind is what might be read as a forest at sunset, subdued but smoldering orange hues shining through.

The wonderful A Quick Shine Before the Dance #1 (1994) has a man who looks like Rayner donning a ritual mask and a wild, feathered headdress reading the paper and getting his shoes shined, the blazing orange wall behind him scrawled with the words Viva Zapata. Leaning up against him is a kind of makeshift staff with a doll and a goofily creepy jack-o’-lantern face.

The Baby Sitters (1994) features a bemused goat standing in a baby carriage with a companion relaxing on the balcony beside, and an upended flaxen-haired doll in front; behind is a tropical green, rain-streaked street.

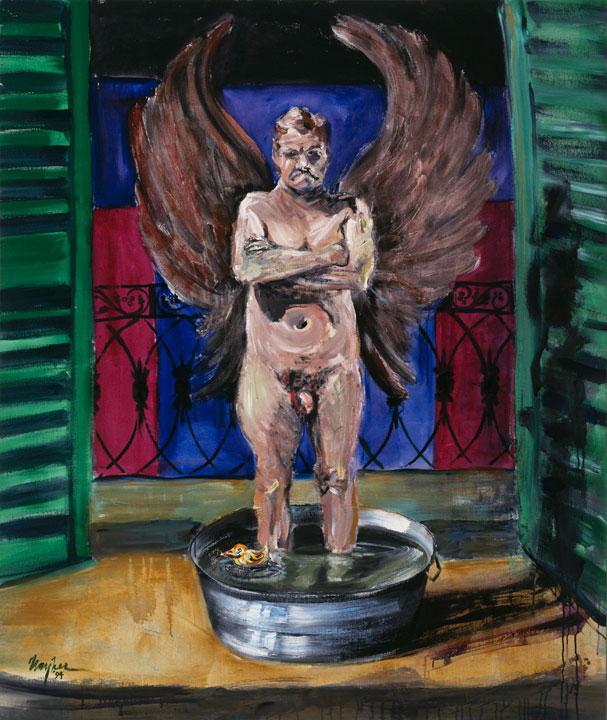

And in what is perhaps the most powerful and revealing painting in the series, Country Bath (Self-Portrait) (1994), Rayner stands naked in a water-filled metal bucket, arms tightly folded, face scowling, broad wings bursting from his shoulders. Green shutters open out from a balcony with wrought-iron railing onto a deep blue night sky. Country Bath (Self-Portrait) is a portrait of the defiant artist in middle age: his body lumpy and sagging, his faced creased, his bearing half angel, half demon, and ready for flight.

It would have been easy to dismiss the paintings in “The Oaxaca Suite” as those of a tired, aging artist seeking inspiration, and in interviews Rayner himself admitted that when he went to Oaxaca, he felt creatively dried up. He would hardly have been the first artist to travel to exotic locales in search of renewal: think of Delacroix in Algeria or Matisse in in Morocco.

But Rayner’s Oaxaca paintings are too direct, self-satirizing, and, for all their lushness of palette, gritty to be mere fantasizing. A Quick Shine Before the Dance #2 (1994), for instance, has another figure that looks like Rayner, in dark glasses and some kind of pagan headdress, getting his shoes shined, a dog sprawled out sleeping beside him.

And in front of the burning flames in Conflagration at the Altar (1994–95), where the torso of the crucified Christ is engulfed in smoke and flame, and the wall is streaming blood, is… a vacuum cleaner. These paintings never lose touch with the ordinary.