Recently, a friend told me that she was sick of the term “polar vortex.” She complained that it seemed like a phrase dreamt up by meteorologists in order to market and sensationalize weather. And indeed, it’s now so frequently hashtagged that it’s easy to become cynical about its origins, or exasperated by its overuse.

But there’s another way to look at this much-Google-searched moniker—and that is as a longtime scientific concept that has only recently come into popular use thanks the increasing incidence and spread of some very real extreme-climate events. It’s possible that in a year or two, the word will become part of our everyday patois, just like “superstorm” and “supercell” seem to have been adopted to various degrees.

This frequent recalibration of language and expectation in the climate-crisis age came to mind in considering Gallery 44‘s current exhibition “What Was Will Be.” In it, Canadian artists Kristie MacDonald and Christina Battle work with evidence of past extreme-weather events in ways that point towards our present situation, as well as our possible future.

MacDonald’s Mechanisms for Correcting the Past (2013) evoked this idea of recalibration most strongly. In it, a table has been altered so that part of its surface repeatedly raises and lowers at an angle. On this raising and lowering surface, a projector is placed, and this device is, in turn, projecting an archival image of a flood-sunken house. The tilting mechanism is adjusted so that when the projector is level, the bottom of the house presents as having collapsed on one side. But when the projector is at its maximum tilt, the house is visually “levelled” with the ground again.

The work has an uncanny effect as the house’s position changes from strange to normal, normal to strange. The tilting motion of the projector itself seems to mimic the motions of a floodwave, cresting and receding ad infinitum.

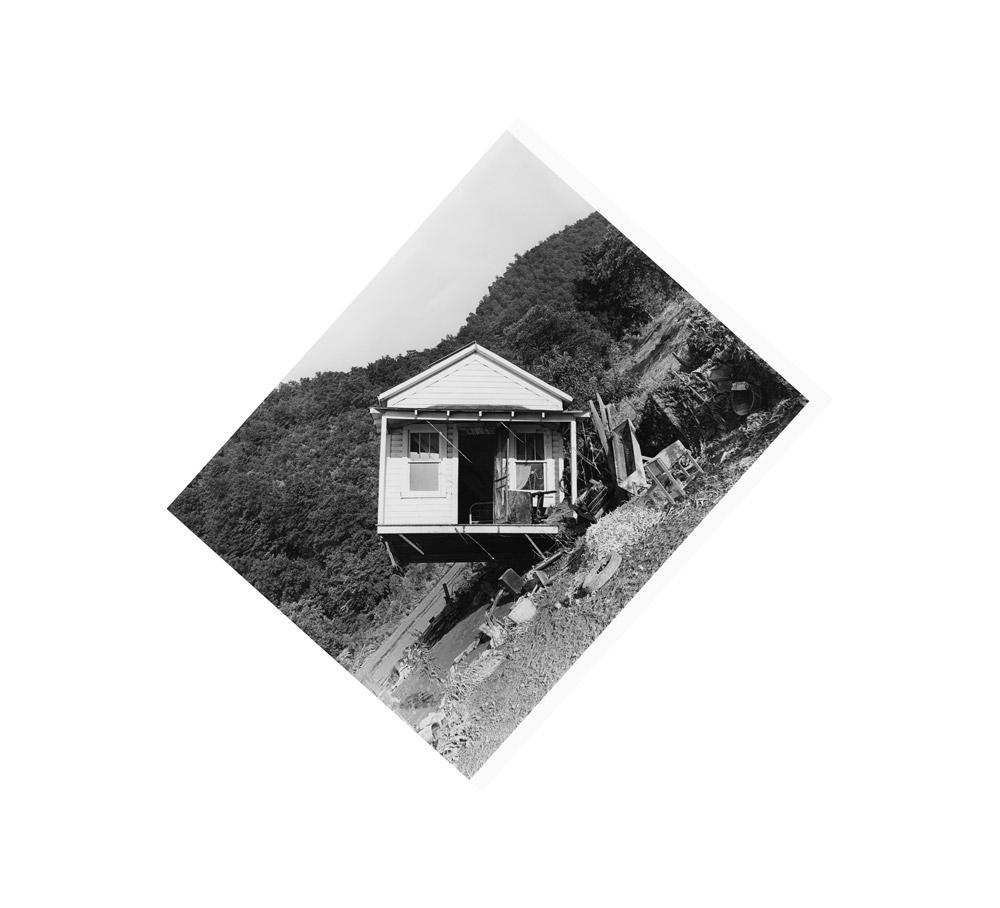

This elegant installation is accompanied by four prints by MacDonald that employ a similar strategy. In each of these, a building damaged by an extreme environmental event—be it ground erosion, a tornado, or another event—is “righted” by tilting a documentary archival image. In some cases, the damage is so extreme that when the image is “corrected” it is difficult to tell which way is up. Again, what I experienced was a sense of both wonder and foreboding around extreme weather and its impacts, as well as our self-perceived ability to “adapt” and “recover” from such events. Perhaps, as the framing of these images suggests, that recovery can be quite artificial.

Christina Battle takes a different approach, exploring the singularly compelling real-life story of Dearfield, Colorado. As Battle’s photograph of a Colorado monument indicates, Dearfield was founded in May 1910 by O.T. Jackson as an “African American agricultural colony.” By 1920, the town had more than 200 residents as well as two churches, a school, a restaurant, and plans to build a canning factory and a college. All that changed with the advent of the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. By 1946, the town had a population of one.

From this photo-summary of Dearfield’s tale, the viewer enters Battle’s video installation, which shows some of the present-day ruins of the town. Yellow wildflowers wave in the breeze around structures of rotting wood and peeling paint. Birdsong is audible, as are some crackling sferics—electromagnetic impulses that result from lightning—that Battle recorded at a very low frequency. Text culled from Depression-era memoirs appears occasionally beneath Battle’s sunny scenes—one recounts dust filling the air to the height of three miles, while another describes “fields sizzling under a metallic sky” and a sense that everything made of metal was “charged with electricity.”

The reference to electricity in Battle’s video and the crackling sound of the sferics heighten a mood of danger, as shiny metallic aluminum panels also line the walls and floor around the video projection. The idea that lightning—or more massive atmospheric extremities such as the Dust Bowl—can indeed strike twice seems to be underlined. What also comes across (more strongly than in MacDonald’s piece) are the very real impacts extreme weather can have on individual communities—and also, perhaps, on utopian cultural dreams.

Though both artists in this show take a less-is-more approach, and I sometimes wished for a little more material, I was left with much to think about.