Some of the most thought-provoking exhibitions are the result of an exquisite balance of aesthetic and political concerns. Frank Shebageget’s solo exhibition “Light Industry” at Ottawa’s Carleton University Art Gallery was one of them.

Shebageget is known for iconographic works rooted in personal history, a critique of colonialist assumptions, and a nuanced understanding of modernism. Focusing on symbols with both Aboriginal and general Canadian significance—such as family dwellings, beaver lodges and bush planes—his work explores the tension between grand narratives of socio-economic development and more marginal narratives of personal livelihood and sacrifice.

Based in Ottawa, Shebageget is originally from Upsala, Ontario, and lived on the Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation (Ojibwa) reserve. His practice is deeply concerned with what curator Ryan Rice once called “colonial influence disguised as progress,” and Shebageget is skilled at exposing such masquerades through a combination of historical and aesthetic references. Lodge (2008), one of the central pieces in the show, is part of an ongoing body of work devoted to the de Havilland Beaver, an iconic wilderness floatplane linked to economic and cultural shifts in remote Northern communities.

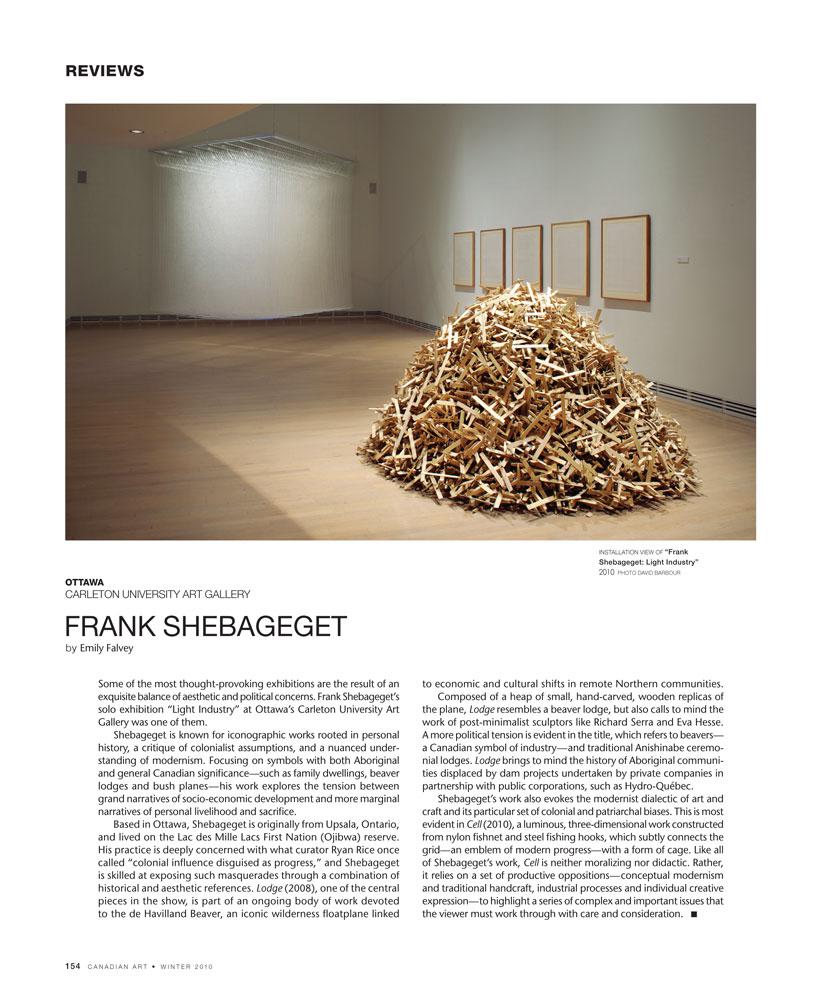

Composed of a heap of small, hand-carved, wooden replicas of the plane, Lodge resembles a beaver lodge, but also calls to mind the work of post-minimalist sculptors like Richard Serra and Eva Hesse. A more political tension is evident in the title, which refers to beavers— a Canadian symbol of industry—and traditional Anishinabe ceremonial lodges. Lodge brings to mind the history of Aboriginal communities displaced by dam projects undertaken by private companies in partnership with public corporations, such as Hydro-Québec.

Shebageget’s work also evokes the modernist dialectic of art and craft and its particular set of colonial and patriarchal biases. This is most evident in Cell (2010), a luminous, three-dimensional work constructed from nylon fishnet and steel fishing hooks, which subtly connects the grid—an emblem of modern progress —with a form of cage. Like all of Shebageget’s work, Cell is neither moralizing nor didactic. Rather, it relies on a set of productive oppositions—conceptual modernism and traditional handcraft, industrial processes and individual creative expression—to highlight a series of complex and important issues that the viewer must work through with care and consideration.

This is an article from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Frank Shebageget, spread from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art

Frank Shebageget, spread from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art