In Eastern Canada, fall is the time when our everyday awareness of colour in nature hits a yearly high, with searing blue skies, flaming reds and oranges and wet, black tree trunks delivering a triumphant last blast of optical pleasure before the long greys and muddy browns of winter. For Montreal artist Francine Savard, however, the near- devotional contemplation of colour is a year-round thing, something she has formalized in a recent series of works currently on show at Diaz Contemporary in Toronto. Savard is known for her conceptual painting practice in which content is reconfigured as schema, and the links between the suggestibility of colour and language are explored. Never better, perhaps, than here.

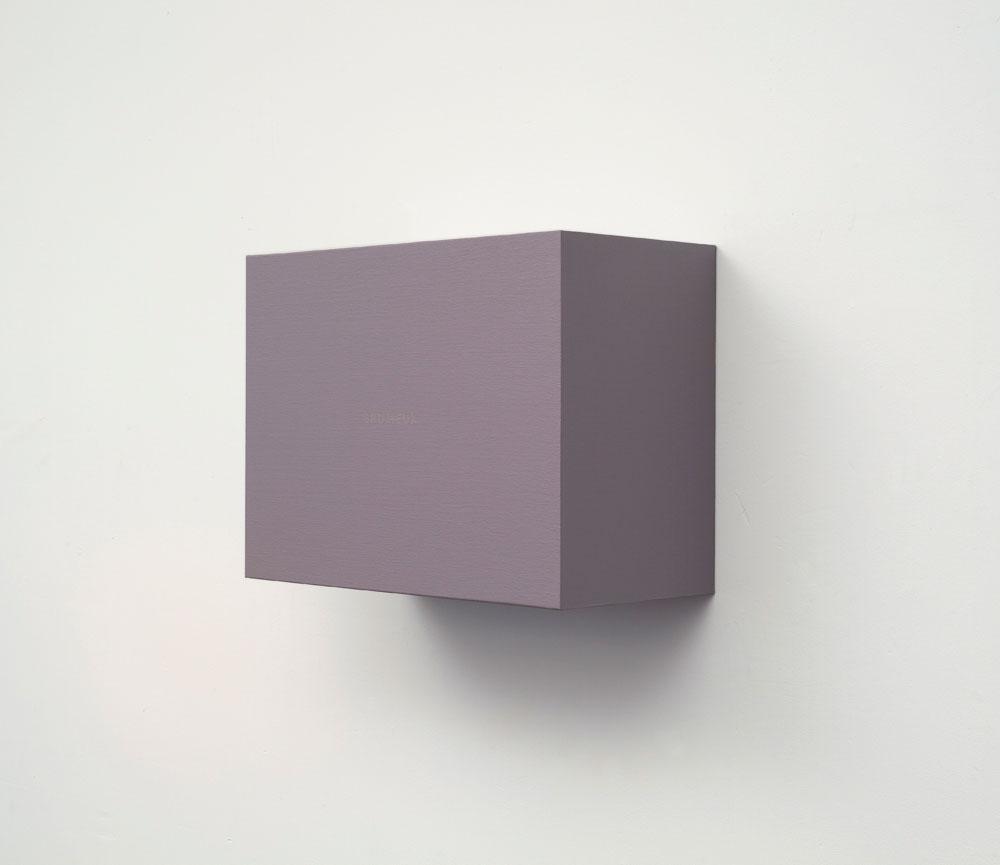

Taking as her starting point the short-form weather forecasts collected from the front page of her Montreal newspaper over a period of nearly a year (think words and phrases like “sunny,” “cloudy,” and “snow flurries”), she then analyzed her findings, making note of the frequency with which certain terms repeated. Next, she calculated volumes based on these frequencies to produce a suite of objects of variable size—canvas stretched over rectangular frames and painted front and side—each of which bears the word or phrase in question and the colour that Savard associated with that word. At the centre of each canvas, the term itself is rendered in small text, subtly embedded in the monochrome field like a language mirage.

Taken as a suite, the work is a portrait of the city Savard loves, with Ensoleillé (a fresh yellow) and Nuageux (pigeon grey) appearing the largest, side by side. Others in the series are more impressionistic in their colour/text associations, like Brumeux—foggy—which appears as a deep ashen purple the colour of a plum, or Venteux—windy—in which grey text dissolves into a creamy pumpkin field. (Could her association have been the autumn leaves that fly, making wind visible?) The object bearing the word Éclaircies—clearing—is a rather surprising Easter-day violet, embodying (to my eye, at least) the buoyancy of spring and the general sense of things looking up.

While some of Savard’s objects have the shallow rectangular form of conventional paintings, others are more sculptural, like Pluie intermittente, a chubby green box whose shape express a kind of fecundity and force, evoking the surging growth of grass on a hot, wet afternoon, or Neige fondante, a silvery, chest-like object that emits the mystic hush of a snowbound day. In a trick of colour mixing, light bounces off the work as if it was radiating from within.

Other works in the show continue Savard’s investigations into weather data, quantification and colour, some of them presenting abstracted schema to embody percentages of wind versus rain, snow or cloud. In whatever form her explorations take, though, Savard represents an unusual marriage between conceptual rigour (she seems pleasurably bound by her underlying systems) and a kind of pure visual poetry, her work recalling some of Quebec painting’s highest moments: the plangent greys of Yves Gaucher, the subtle monochromes of Claude Tousignant, and the contemporary experiments of Chris Kline, whose colours can bloom as delicate as hoarfrost, or lie rich and sweet as Spanish caramel on the picture plane.

In the end, Savard’s show stands as a kindred testament to Minimal and Conceptual art’s capacity to embody realms of feeling without gestural displays of brushwork and painterly heavy breathing. Rather, a disciplined set of decisions delivers us to the doorstep of the sublime.