Eli Bornowsky is an intelligent younger artist based in Vancouver whose work has been seen in Toronto more than once in RBC Canadian Painting Competition exhibitions. His current show at G Gallery is light and even comical in a very contemporary way—the work is partly formalist and partly conceptualist.

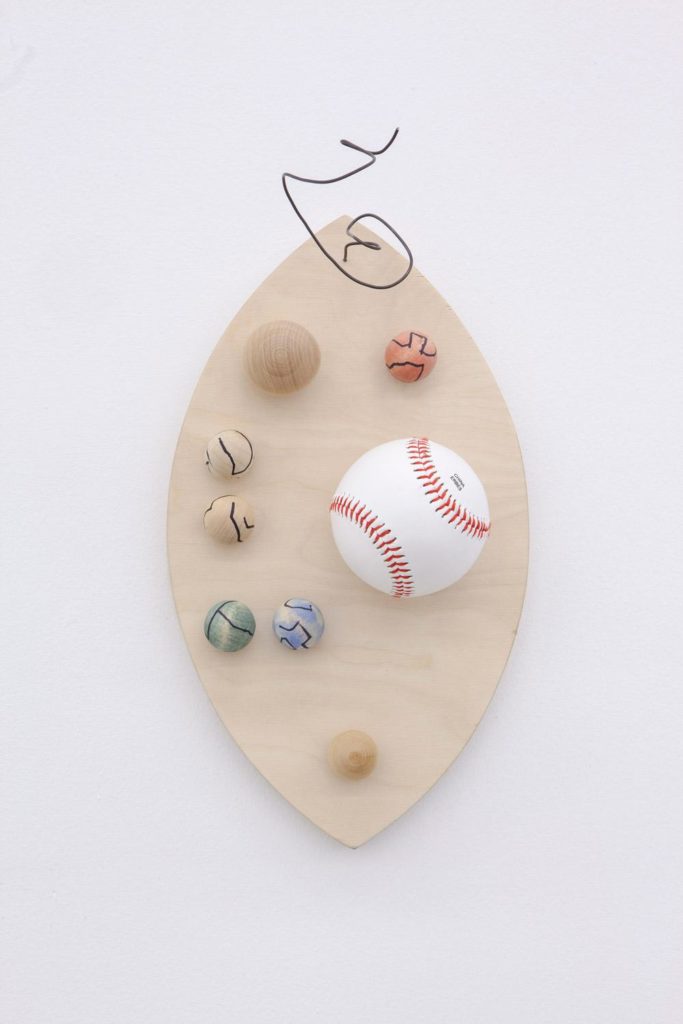

The show alternates two repeating forms. There are a number of small panels variously shaped and painted and stuck over with wooden balls, themselves sometimes covered with drawn lines, mostly from felt markers. Between each pair of panels is a painted wooden pole hanging from a hook, and each pole has a paint-smeared rag dangling from its bottom end.

The former elements (the panels) are, presumably, the art, while the latter are the implements that made it—because the poles with rags do look like ineffectual paintbrushes or mops. In fact, mops have been used as art implements, notably by de Kooning. Bornowsky’s particular “brushes” or mops couldn’t have had much to do with the paintings on display, because those are quite fastidious and tidy, but the conceptual joke is that Modernist painting is supposed to reveal its own procedures, the more so as those procedures are evidently impossible or bound for failure anyway.

There is something clownish about the paint sticks, particularly as they direct us downwards to contemplation of the abject bits of cloth, perhaps retrieved from a studio floor. Bornowsky here seems to have caught the spirit and feel of head-banging, embarrassing, self-abusing, elite gallery art—think the clowns of Bruce Nauman or Paul McCarthy.

And why shouldn’t Bornowsky be clownish? But this is nothing new; it’s 30 years old, at least. Some of us remember Werner Büttner, Martin Kippenberger, Jiri Dokoupil and Walter Dahn, to mention a few painterly humorists who understood that painting can live and thrive through humour particularly if the joke is on itself—only if the joke is on itself. So this is a good occasion to also notice and remember that whatever is conceptual is today passé. I’m sure that Bornowsky would agree with that, at least, because like most painters of his generation, he is very serious about his medium. He’s not trying to kick over the traces.

The formalist interest of this exhibition lies in the small wooden balls attached to the differently shaped panels between the paint sticks. This component has the feel of earnest formal experiment, though again rather lightly undertaken. Personally, I think that spheres bearing interwoven patterns of drawn lines are very interesting things indeed. But Bornowsky does not take that idea to the limit. Instead, by working small and providing a painted surface for the balls to lie against—a plane, in other words—he keeps it as an image. These same balls sized three feet across and hanging in the gallery would be a challenge. As it is, the most interesting painting gesture in the show is attenuated by its own conceptuality. It’s too much of an idea, and not enough of an experience.

Make no mistake, lightness and humour are good qualities in art, and formal experimentation is a very worthwhile element. Bornowsky’s show could be seen as a sketch, essay or meditation on the contrasting—but maybe also interrelated—elements of concept and form in painting.

In the Toronto context, I find the show distinguished; it’s better than most of what I see. It has a kind of compression. We can feel the presence of a mind, and that’s rare enough, but the seriousness and commitment are dressed up as playful and funky decor. In itself this is not a bad thing—in a way, it is very smart.

Where I have trouble is with the cleanness and crispness of the work, with the fact that it is so well made. And yet, I don’t hold that against Bornowsky. It’s not his fault that good taste has caught up with everything an artist might imagine to do. In fact, it’s hard to see how the issue would even arrive for him; he buys the wooden balls, and they just are as they are, there is no reason to make them look differently; the poles have to be painted, and they might as well be painted evenly; we couldn’t even imagine that the degree of messiness against which a paint rag needs to be measured.

The ability to make something is a prerequisite for the status of artist, but every artist knows that facility can be a trap. Yet facility or the lack of it is not even at issue. The problem is the newness and cleanness of the commodity—but what is an artist to do if dirtiness and awkward construction no longer necessarily have expressive value or meaning? Drips, splatters and messes of all kinds are completely conventional and are easily assimilated to the minimalist decor of any Toronto condo—as long as they fit in a frame.

Today, great art should transcend the distinction between well and badly made, but there is no formula that will enable that. I recently saw some examples of Frank Stella’s Moby Dick series, which manage the trick, and it feels very good to see it done because it takes us entirely out of the aforementioned dilemmas. Feeling prevails over both doubts and convictions.

I wish that our younger artists would address themselves to this problem, because both wit and intelligence are weakened by a too-competent and tidy execution. The whole issue of technical skill is an open question, and an encounter with that would make a good beginning for both painting and sculpture today.