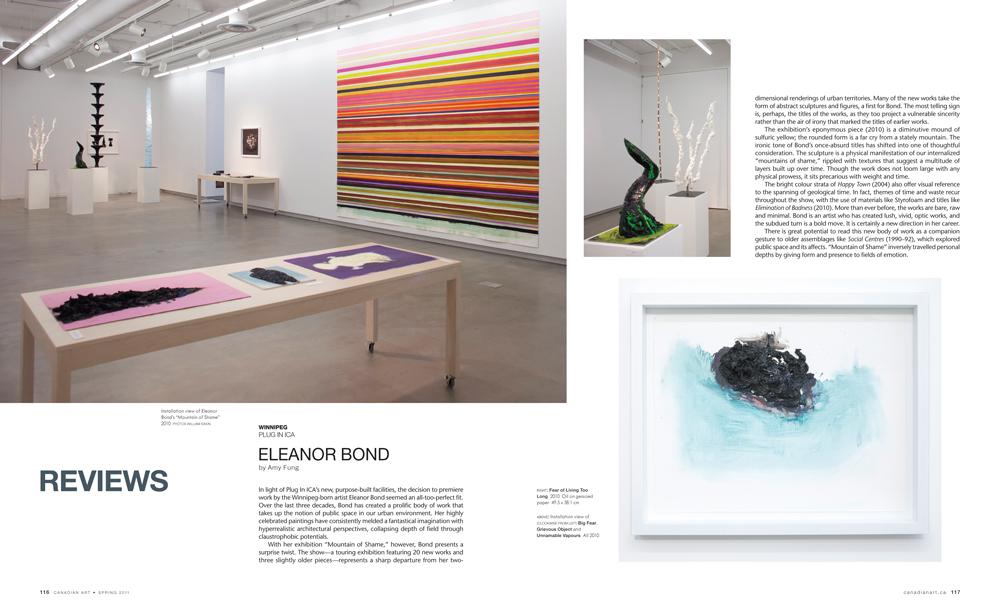

In light of Plug In ICA’s new, purpose-built facilities, the decision to premiere work by the Winnipeg-born artist Eleanor Bond seemed an all-too-perfect fit. Over the last three decades, Bond has created a prolific body of work that takes up the notion of public space in our urban environment. Her highly celebrated paintings have consistently melded a fantastical imagination with hyperrealistic architectural perspectives, collapsing depth of field through claustrophobic potentials.

With her exhibition “Mountain of Shame,” however, Bond presents a surprise twist. The show—a touring exhibition featuring 20 new works and three slightly older pieces—represents a sharp departure from her two-dimensional renderings of urban territories. Many of the new works take the form of abstract sculptures and figures, a first for Bond. The most telling sign is, perhaps, the titles of the works, as they too project a vulnerable sincerity rather than the air of irony that marked the titles of earlier works.

The exhibition’s eponymous piece (2010) is a diminutive mound of sulfuric yellow; the rounded form is a far cry from a stately mountain. The ironic tone of Bond’s once-absurd titles has shifted into one of thoughtful consideration. The sculpture is a physical manifestation of our internalized “mountains of shame,” rippled with textures that suggest a multitude of layers built up over time. Though the work does not loom large with any physical prowess, it sits precarious with weight and time.

The bright colour strata of Happy Town (2004) also offer visual reference to the spanning of geological time. In fact, themes of time and waste recur throughout the show, with the use of materials like Styrofoam and titles like Elimination of Badness (2010). More than ever before, the works are bare, raw and minimal. Bond is an artist who has created lush, vivid, optic works, and the subdued turn is a bold move. It is certainly a new direction in her career.

There is great potential to read this new body of work as a companion gesture to older assemblages like Social Centres (1990–92), which explored public space and its affects. “Mountain of Shame” inversely travelled personal depths by giving form and presence to fields of emotion.

This is an article from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art