“Dreamland: Textiles and the Canadian Landscape,” the lyrical summer exhibition at the Textile Museum of Canada, is aptly titled after the first book of poetry published in post-Confederation Canada (Charles Mair’sDreamland of 1868). Through a series of poetic juxtapositions, exhibition curators Shauna McCabe, Natalia Nekrassova, Sarah Quinton and Roxane Shaughnessy help to draw vintage Canadiana from the museum’s permanent collection into dialogue with works of contemporary art. They suggest that art and craft can work in similar ways to open up opportunities for contemplation, storytelling and reverie.

Although a “waste not, want not” imperative often informed the making of the quilts, mats, carpets and toys on display in this exhibition, the results are far from prosaic. Confronted with threadbare scraps of cloth, the weavers of Quebec’s famed catalogne carpets saw not dishrags, but potential for metamorphosis.

In “Dreamland,” a richly variegated cluster of these runners hangs opposite Montreal artist Jérôme Fortin’s Self Portrait no. 4 (2012). Fortin salvages sheets of paper from such throwaway sources as tourist maps, comic strips, musical scores and phone books; often these have some kind of personal association. Here, he folds the paper in a manner that evokes origami, creating long, graceful ribbons that drape like a Japanese kimono from a bamboo support.

The same urge to transform the banal into the beautiful is evident inStag (2012) a spectacular wall hanging made from thousands of small squares of fabric joined together by delicate threads. According to its maker, Grant Heaps, the original materials are as varied as a green-and-white checked shirt belonging to an ex-lover and a golden costume that had once been worn in the ballet The Nutcracker. (The artist’s day job is assistant wardrobe co-ordinator at the National Ballet of Canada.) Suspended in a web so light it is barely there, the shimmering bits of cotton, wool, linen, nylon, polyester and silk appear almost to float on the wall. Heaps took the image of the stag from a standard needlepoint design; the wonder is the way in which he has invested a corny stereotype of Canadiana with an everything-old-is-new-again spirit of optimism and romance.

Journeys are a recurrent theme in “Dreamland.” London, Ontario–based artist Jason McLean’s mixed-media work America in the Fall(2011) is a visual scrapbook of old bus tickets and road memorabilia collaged onto a crumpled map of North America, its rips and fissures stitched together with pink thread.

The utilitarian and the fantastic merge in a hooked rug from the Grenfell Mission (circa 1936–39) that shows the god of wind blowing on a blue ocean full of ships and whales around the island of Newfoundland. Set foot on this carpet, imaginatively speaking, and one is transported to a mythic realm.

A 1920s quilt tells the story of the immigration to Canada of the quilter’s Scottish ancestors a century earlier. The lively border of appliquéd fruits and leaves surrounding the central images of rigged ships and playful figures suggests the descendant’s view that the outcome of the voyage was a happy one. To sleep beneath it, one imagines, would be a nightly affirmation of continuity with the past.

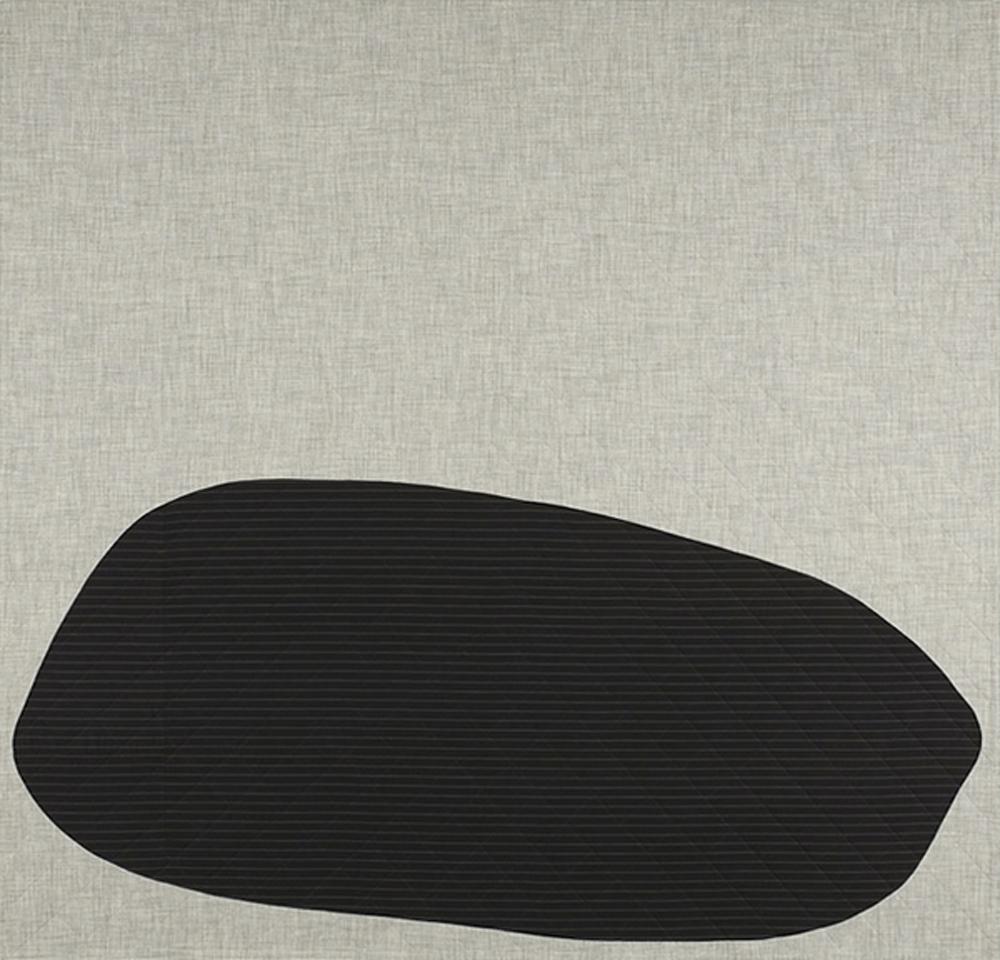

A shared preoccupation with memory links Barbara Todd’s elegant, minimalist quilts to their folksy, pictorial predecessors. The enigmatic, stone-like shape that nudges uneasily against the edges of the square frame in …all your troubles fall away (2008) could be a free-floating metaphor for anxiety. (The quilt’s title comes from a quote by Canadian painter Agnes Martin: “If you can imagine that you’re a rock / all your troubles fall away.”) Yet it also references actual beach pebbles gathered at a site on Lake Huron central to her family’s history. In a ritualistic 2005 diary project (displayed in a nearby case), the artist made daily arrangements of the pebbles and combined them with personally relevant texts.

Sensitivity to the revelatory possibilities of everyday materials and occurrences characterizes much of the best work in the exhibition. Nowhere is that heightened awareness better demonstrated than in Michael Snow’s Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids) (2002). Hard to believe, perhaps, but the hour-long film of curtains flapping sensuously and rhythmically in the wind against the open window of his summer cabin in Newfoundland makes for ecstatic viewing. As Snow remarked on the occasion of the work’s exhibition in New York several years ago: “While on one level, Solar Breath is merely a fixed-camera documentary recording, it is also the result of years of attention…. Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids) is 62 minutes of the most beautiful, eloquent movements and pliages that the sun, wind, windows and curtain have yet composed. Chance and choice co-exist.”

That the curators chose to include Snow’s masterpiece in a show about textiles demonstrates their ability to think outside the box. Defined by a restricted mandate, operating on a parsimonious budget and housed in an unglamorous, easy-to-miss building, the Textile Museum nonetheless presents some of the most thoughtful and original curatorial programming in Toronto. In doing so, it illustrates one of the underlying arguments of “Dreamland”—that imagination is the best antidote to life’s limitations.