For more than 30 years now, North Vancouver’s Presentation House Gallery has schooled numerous generations of gallery-goers on the finer points of historical and contemporary lens-based practices. Through a program attentive to local, national and international artists who work in photography, film and video, the gallery also mounts exhibitions of those for whom these mediums are present but not primary. While this last aspect has allowed for intriguing monographic exhibitions about interdisciplinary artists such as Glenn Lewis and Michael Morris, it is the gallery’s current group exhibition, guest-curated by an artist for whom the camera remains central, that has the potential to turn a lesson into a course.

Like many medium-specific Vancouver-based artists (think Mina Totino in painting and Liz Magor in sculpture), “Dream Location” curator Stephen Waddell is well-versed in photography’s social and formal histories—enough to add writing, lecturing and curation to his skill set. However, unlike artist Roy Arden, who conceived and curated the notable “After Photography” exhibition at Monte Clark Gallery in 1999, Waddell is less interested in the medium’s “obligation to address its history and canons” than in “works that exemplify each artist’s particular aesthetic or poetic sensibility and uses their forays into photography to look within the larger context of their art production.”

Taking his cue from Walker Evans‘s 1962 Harper’s Bazaar photo-essay “The Unposed Portrait,” where Evans implores photographers to get out of their studios and mine “dream ‘locations'” such as New York City’s subway system for content, Waddell has extended Evans’s call to include those curious not about the future of the medium as an end in itself, but its material and heuristic means. To demonstrate this, he has brought together an impressive list of practitioners—Evans, Runa Islam, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Elad Lassry, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter—who, apart from Evans and Lassry, are known less for their photography than their paintings, sculptures and films.

Mounted in PHG’s smaller east gallery is Islam’s Emergence (2011), a mesmerizing, 2-minute-54-second 35mm film that has as its subject a degraded glass negative image of dogs noshing on a dead horse in the historically loaded city of Tehran. Central to this work is the method by which the narrative carried in this negative comes and goes through the darkroom process, particularly how this process is captured through another medium: motion-picture film. Indeed, that Waddell chooses not to supply the date of this negative (it’s from the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1905 to 1911) allows the viewer to arrive at the historical question of when this image could have been captured through a poetry analogous to the production of its print—a print that, in this instance, begins with a red monochromatic field supplied by the darkroom light. Apart from, and perhaps as a result of, this work’s ability to draw the viewer into repeated viewings, Emergence functions as an equally re-readable prologue to the larger exhibition, where the relationship between photography and other mediums is less apparent.

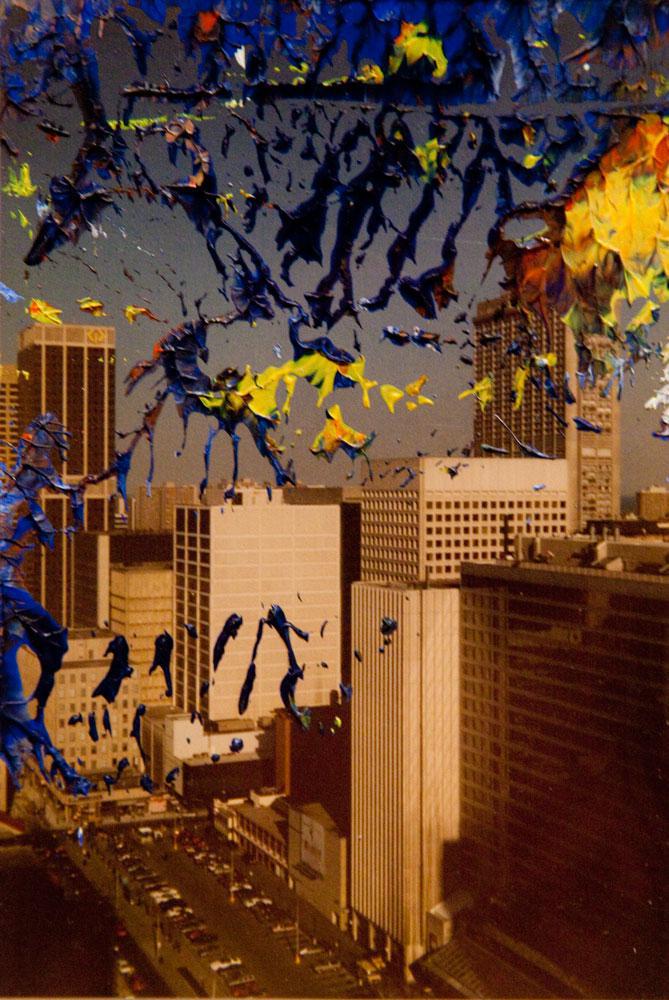

Much of the exhibition resides in PHG’s west gallery. Here, Evans’s 1930s and 40s black-and-white subway portraits of deadpan New Yorkers are interspersed amidst a gently spaced horizontal ring of pictures: images taken by Kirchner of costumed friends and models at his painting and sculpture studio between 1915 and 1921; Lassry’s very recent black-and-white screenprint portraits based on sources that, in their wide-ranging availability (from the documentarian to the commercially staged), paradoxically achieve both a haunting ubiquity and a familiar liminality; Polke’s two-tiered set of 10 Cibachrome prints entitled Untitled (Green) (1992), made through the exposure of uranium slabs to photosensitive film; and, on the inside wall just inside the south gallery entrance, a pair of Richter’s oil-on-photograph pictures, the first of which, Toronto 1988 (1988), reminds us that cities are people too.

Common to all of the pictures in this ring is what we experience in Emergence: transition. From the process of making a photographic print, to the painter’s models posing amongst his sculptures, to models approximating poses that move not from past to present but from staged to unstaged, to one element finding form in another. But is this ground, as it were, enough to support the harder, more melodic proposition around aesthetic sensibilities that Waddell sets up at the beginning of his essay? I am not sure it needs to be. The ring itself is an elegant thing, encrusted with inexplicable recurrences, such as pictures comprised of women in pairs, as seen in works by Kirchner, Evans and, on the wall that greets us as we enter the west gallery, a colour print by Lassry.

But if a heavier case is to be made for the exhibition’s lighter emphasis on transition, it can be found near the north entrance to the gallery proper: a large, appropriately unframed picture by Waddell of a wall in what could be his studio, where pictures of various shapes, locations and themes (some of which might be made in the same spirit as those he has chosen for his exhibition) hang as if in the midst of consideration. What that consideration pertains to is, in all likelihood, the development of a future work by an artist-curator for whom transition is a subject in itself.