Douglas Coupland’s exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery took up the museum’s first floor. If you entered and went to the right, you were in a room stuffed with Canadian kitsch: old beer bottles, hockey masks and furniture that referenced the FLQ crisis and the suburban “905” area around Toronto. If you went to the left, you were in, apparently, Coupland’s brain: fabricated highway signs from West Germany (where he was born, on a Royal Canadian Air Force base, in 1961), a stump from Gordon Smith’s patio and other bric-a-brac. So Coupland is a hoarder (as he admitted at an event titled “The Future of the Future” in early June). But if you made your way past these unpromising entryways, you could find some art.

The best art in this show turned out, surprisingly, to be paintings. There were, in a room called “Secret Handshake,” what appeared to be large-scale Cubist versions of Group of Seven and Emily Carr paintings. The premise of these works is that iconic paintings (Carr’s Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky [1935], a Tom Thomson sunset, a Lawren Harris island) have, via their digital degeneration, been updated (or “refreshed,” as computer-speak has it) into blocky, sharpened and brilliant acrylic versions of themselves. The paintings work and do not work at the same time. The premise is great—like Coupland’s public sculpture Digital Orca (2010), these works comment on how we typically see art now: not in a museum or gallery, not in an art magazine or textbook, but online. But then the subject matter is less promising: the Group of Seven, again, really? Emily Carr, again, really?

The same yes/no reading (or “epic fail,” to quote the Internet vernacular that Coupland cites) applied for the room he titled “The Pop Explosion,” which held Roy Lichtenstein and Piet Mondrian works reimagined via QR codes and other machine-readable graphics. So Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942–43) is now a colourful version of those scannable images that real-estate agents and supermarket flyers favour. Or a Post-it Note is imaged via Ben-Day dots. Again, great premises. Painting today has to vie with commercial imagery. But this last strategy—the gesture towards Lichtenstein’s appropriation of cartoon technology, the Ben-Day dots process by which comics were printed in the mid-20th century—has itself been overtaken by history, by the technology that Coupland loves (or loves to hate, or hates to love…) so much. Surely part of Lichtenstein’s impact had to do with how he made what was previously unseeable, or overlooked—the tiny dots on the Sunday newspaper comics—big, part of the artwork. Pop was a comment on the “mechanical reproduction,” as Walter Benjamin put it, of commercial culture. The ubiquity of QR codes or luggage tags means that Coupland will have to come up with something better.

And that is what, I would argue, he does in the works he offered as “The 21st Century Condition,” and especially the series of paintings that treat the World Trade Center attacks and Osama bin Laden. These paintings, roughly five-by-five feet in size, are designed to be seen through a smartphone lens, where their obscured images are slightly clarified. That is, each work shows a picture that is newspaper-ish in quality and grain, and which has been further degraded through scopic or digital ways. The scale effect in the room worked so that the images were the size of a newspaper photograph from across the breakfast table: middle-class media consumption of the recent past. What to the naked eye is a blur of lines resolves itself into an image of a jumper—or perhaps two—falling in front of the World Trade Center. This is a digital update of Hans Holbein’s anamorphic skull—the smear at the bottom of The Ambassadors (1533) that you can only see from the edge of the work, rather than from looking at it head-on. A cryptic code that once required you to move your body in space, in the gallery or room, to see it, has been reset for a visual puzzle resolved via handheld technology.

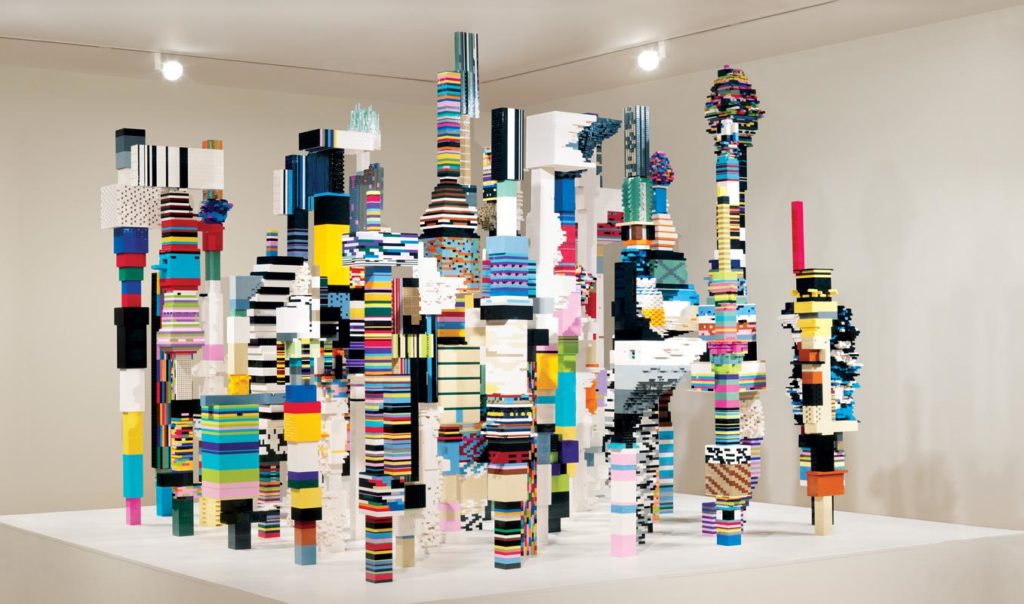

So I think these are important artworks—whether they work, as I argue Coupland’s paintings about political violence do; or do not, as in his Pop and Group of Seven/Carr works. They reflect on the technological mediation of iconic imagery. But I’m not sure that much of the rest of the show belongs in an art museum. Given Coupland’s infantile material—he has a room of Lego—I revisited the exhibition with my 13-year-old son, to see if perhaps I am just not Coupland’s intended audience. He has said, for instance, that his Gum Head (2014) public sculpture outside the gallery is designed to lure in those who would not normally enter an art gallery, which is, of course, the purpose of summer shows in a tourist-destination city like Vancouver. My son liked the Lego art a lot. And walking through the room of Canadian kitsch again, I saw a blot or a stain, a leak under an ice machine. Douglas Coupland’s brain is leaking, and it was there on display at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

This is an article from the Fall 2014 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents.

This article was corrected on December 16, 2014. The original post contained the fragment of an HTML tag which may have confused some readers.