“I thought it would be exciting to bring together a group of artists of various disciplines, without rules or guidelines, and see what happens. And then bring that ‘something’ on the road.”

Jon Claytor is in love with the idea of a travelling variety show. With the first-ever SappyFest artist residency, the visual artist and co-founder of independent New Brunswick music festival SappyFest has put together something that might come pretty close.

In early May, the residency brought together 10 artists to make work and put on a show in Sackville. In addition to Claytor, other artists participating were fellow SappyFest co-founder Paul Henderson, musicians Shotgun Jimmie, Steven Lambke and Michael Feuerstack, writer Ian Roy and visual artists Amy Siegel, Graeme Patterson, Mitchell Wiebe and Amanda Fauteux. All of the artists bring a history of collaboration, interdisciplinary practice and a history of involvement with SappyFest, be it as a performer, organizer or volunteer.

The show, named after the residency’s theme of “Wish You Were Here,” was held on May 14 at Sackville’s Thunder and Lightning. Now six of the artists are taking to the road, touring to Charlottetown, Fredericton, Halifax and Sydney, effectively stretching “here” a little further.

A drum kit set up at Thunder and Lightning in Sackville alongside wall works by local artists Andrea Mortson and Erik Edson. Photo: Graeme Patterson.

While talking with Claytor via email in the week before the residency, the artist mentions that he’s never done an artist residency himself, as he never wanted to be away from his family for that long. SappyFest, he says, seemed like a good vehicle for creating that experience in a way that he could access it, going on to speculate that perhaps the best way to think of the event is as “a giant residency for the audience.”

It’s a lovely thought, and one that does, in some ways, ring true. The artists Claytor brought in all have strong connections to one another and to SappyFest. Not realizing this at first, while researching the artists involved online, I sometimes felt like I was creeping an entire social circle, as relationships, collaborations and connections became evident.

“The residency has been on my wish list of things to do in Sackville ever since I opened Thunder and Lightning (with Paul Henderson in 2013), ” Claytor explained, “I have this little bar with a bowling alley with six studios above it. It seems like a perfect place for collaboration and chaos.”

***

The show at Thunder and Lightning on May 14 began by giving visitors the opportunity to visit the studios where most of the artists had worked throughout the week, with both finished work and sketches of various sorts on view.

Fauteux, who is also the program manager at Sackville’s artist-run Struts Gallery, traced the outline of every piece of missing paint from the floor of her studio, the flaws documented in light pencil on tracing paper hung in a stack from a clip on the wall. Each chip was then filled in with wood-panelled vinyl, which was in turn covered with flocking that matched the paint on the floor. There was something poetic in the great care, even reverence, Fauteux gave to this modest space. With the room bearing some intriguing circa-1900 architectural features, Fauteux’s work here made me think of Emily Dickinson and her environs—a small Victorian room made somehow monumental by the complexity of the interior world of its occupant.

Amanda Fauteux made subtle interventions into her residency studio space, tracing outlines of every piece of paint missing from the floor. Photo: Amanda Fauteux.

Henderson and Siegel shared a studio space, and in a nod to the theme, each artist’s work drew attention to something that could not be seen. Henderson, a designer, used NOW Magazine pages as the base for a series of collages where the elements of layout and design were foregrounded to the point of swallowing up the noise of the page’s content entirely. Looking at whole pages of yellow, cyan, magenta and white, it is as if the ink revolted. With only the borders and margins remaining, Henderson later told me he thinks of this as “leaving the architecture of the page intact.”

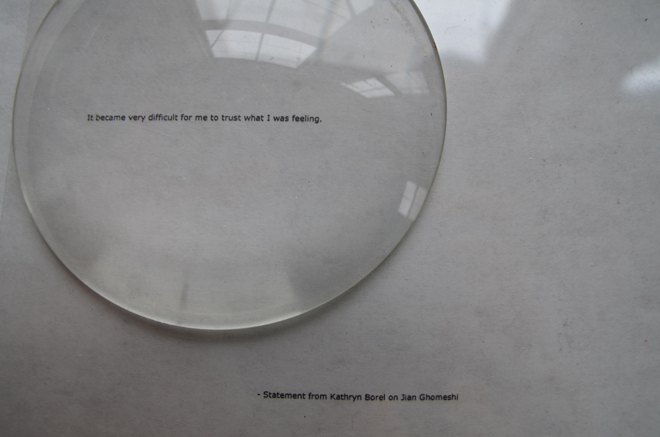

Siegel’s work included a collection of sculpture, video and works on paper. Much of the work included was white, the honeycomb form of a hanging textile visible through soft modulations in light and shadow. A fragment of “The Great Amherst Mystery,” a ghost story, could be read on the wall. Below this, a print on a table showed five small engravings of a girl in bed being preyed upon by a horned devil that grows successively larger in each image. Drawings that appear to be illustrations from self-defence manuals were placed beside a quotation from former CBC employee Kathryn Borel about her experience working with Jian Ghomeshi: “It became very difficult for me to trust what I was feeling.” Given that Siegel’s past work has included collaborations with theatre companies involving projections and shadow puppetry, it’s tempting to imagine how these elements could perhaps form the base of a performance.

Artist Amy Siegel created a work based on Kathryn Borel’s recent statement about Jian Ghomeshi, placing it alongside illustrations from self-defence manuals. Photo: Amy Siegel.

In addition to organizing the event, Claytor had a standout video in a cupboard at the end of the hall. Visible only through the partially opened door, the video presents the strange and disjointed narrative of a trip to a mysterious island where, seemingly, dangers lurk. The video’s aesthetic is evocative of ’60s and ’70s-era nature films, à la Hinterland Who’s Who, or Leonard Nimoy’s In Search of…—all grainy pictures and glimmering, sun-drenched water with dark patches of shadow, and the odd bit of fur and claw thrown in. The entire piece is in fact an iPhone film of Claytor’s own Instagram account.

Musicians Jimmie and Lambke and writer Roy each opened up their respective studio in addition to performing in the “Wish You Were Here” tour. Lambke’s studio offered some pieces of writing complete with his handwritten notes and strikethroughs—the kind of material that provides an interesting insight into a writer’s process, but that feels somehow rude to pore over too closely. Jimmie hung a series of “spin paintings” that were made for use in his music video for “Field of Trampolines”; the works most overtly reference psychedelia, but they’re also evocative of the cross-section of a fir tree, the branches and needles spinning out from the centre.

Before closing up the studios in anticipation of the performance downstairs, Roy gathered those in attendance to the kitchen to read a story about a boy who could fly. As I looked around at more than 30 people crowded into a small kitchen up against white goods and tile, I was reminded of the saying that all parties in the Maritimes end up in the kitchen. Roy’s delivery was concise and direct as he recounted a fanciful yet somehow cautionary tale, with ambient spaceship sounds provided by Jimmie through a set-up mounted on the stove.

Writer Ian Roy explored some musical riffs during his SappyFest residency studio time.

Downstairs, in the bowling alley accessed through the back of the pub, Patterson designed a strange grotto with swags of rose-coloured fabric hung like great baroque clamshells, lamé on the ceiling and white shag carpet on the floor. This was the stage for performances by Feuerstack, Roy, Lambke, Jimmie and G.L.A.M. Bats (a cabaret duo of Patterson and Wiebe).

The first to take the stage, Feuerstack played songs that felt quiet even when they were loud. They’re full of asides and subtle humour that come from Feuerstack’s matter-of-fact delivery. It occurred to me that all of the things that make Feuerstack a rewarding performer would probably also make him an infuriating person to argue with.

Roy hosted the evening, and read a piece about a man who comes to understand himself better through the process of buying a suit. The piece has a self-effacing quality and a light humour that suited the tone of the evening well.

Next Lambke performed, and I was struck by the engaging tension in his voice as he sang; it seemed to hold a sense of urgency—even forcefulness—that belied his low, gentle tone. This music is powerful in the way that wind can be powerful, slowly shaping rock, or water stone through repetition and insistence. Against the backdrop of Patterson’s sparkly grotto, it was a bit like attending a performance inside a snow globe.

Jimmie brought the kind of guileless enthusiasm for playing music that put the crowd in the palm of his hand. Name-checking local venues and bringing his fellow musicians up to play with him, Jimmie played his heart out and sang the kind of scrappy rock ’n’ roll that Atlantic Canada so likes.

As the G.L.A.M. Bats took to the grotto-cum-stage, Wiebe and Patterson appeared as virtual set pieces come to life. G.L.A.M. Bats dressed for the occasion, wearing costumes made for them by Halifax designer Sherry Lynn Jollymore including suits, capelets, wigs and animal face paint. As Wiebe’s daft banter segued into numbers like “Lampshade Eyes,” Patterson occasionally lent a well-timed grunt or shrill falsetto backup to round out Wiebe’s smooth croon. The overall effect was something akin to Wayne Newton getting a makeover from the Hilarious House of Frightenstein, as scored by Duran Duran.

The G.L.A.M. Bats (comprised of artists Graeme Patterson and Mitchell Wiebe) perform in the modified bowling-alley-grotto-cum-stage at Thunder and Lightning. Photo: Elizabeth Grant.

***

When asked how he thinks that the visual-arts community in Sackville has shaped the kind of event SappyFest has become, Claytor tells me that SappyFest and Sackville’s visual-arts community are one and the same.

“It is a festival created and run by artists and was born out of Sackville’s artist-run centre Struts, where like minds gathered and dreamed a dream. In Sackville everything and everyone is connected.”

One of the strongest impressions left on me by “Wish You Were Here” was the respect the participating artists feel for each other, and for the community that has, in different ways, brought them together.

In a zine made by Henderson to document the residency, Siegel shared some thoughts on the theme:

“Here, we were offered a gift. To take some days to conjure something new: a word, a melody, a structure, an image, a nothing. Jon Claytor is a wizard who practices deep swamp magic; to be working at 23 Bridge Street is to hold hands with the magi he’s gathered and plunge into the portal.”

Currently based in Saint John, New Brunswick, Elizabeth Grant is a freelance writer and painter with a Masters of Letters in Fine Art Practice from the Glasgow School of Art. In September 2016, Grant will begin the MA in Art Business at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art in New York. Follow her on Twitter @LitszenGrant.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

The first-ever SappyFest artist residency brought 10 artists and musicians together to collaborate in studio spaces above Sackville's Thunder and Lightning. Photo: Graeme Patterson.

The first-ever SappyFest artist residency brought 10 artists and musicians together to collaborate in studio spaces above Sackville's Thunder and Lightning. Photo: Graeme Patterson.