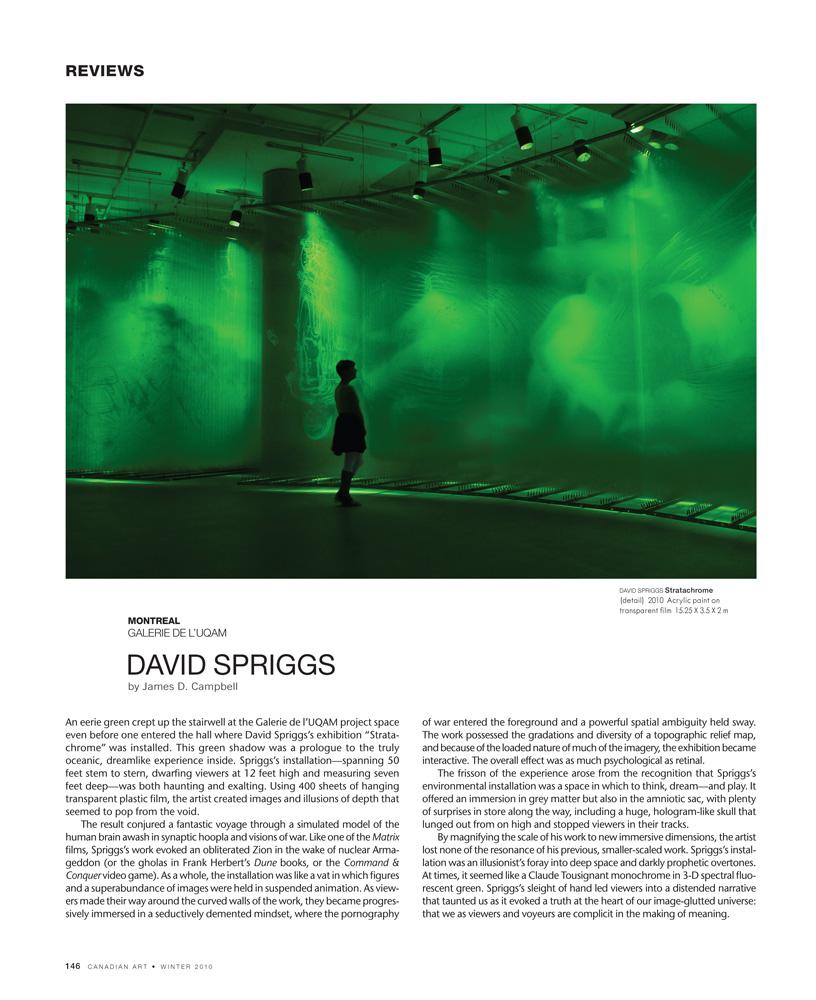

An eerie green crept up the stairwell at the Galerie de l’UQAM project space even before one entered the hall where David Spriggs’s exhibition “Stratachrome” was installed. This green shadow was a prologue to the truly oceanic, dreamlike experience inside. Spriggs’s installation—spanning 50 feet stem to stern, dwarfing viewers at 12 feet high and measuring seven feet deep—was both haunting and exalting. Using 400 sheets of hanging transparent plastic film, the artist created images and illusions of depth that seemed to pop from the void.

The result conjured a fantastic voyage through a simulated model of the human brain awash in synaptic hoopla and visions of war. Like one of the Matrix films, Spriggs’s work evoked an obliterated Zion in the wake of nuclear Armageddon (or the gholas in Frank Herbert’s Dune books, or the Command & Conquer video game). As a whole, the installation was like a vat in which figures and a superabundance of images were held in suspended animation. As viewers made their way around the curved walls of the work, they became progressively immersed in a seductively demented mindset, where the pornography of war entered the foreground and a powerful spatial ambiguity held sway. The work possessed the gradations and diversity of a topographic relief map, and because of the loaded nature of much of the imagery, the exhibition became

interactive. The overall effect was as much psychological as retinal.

The frisson of the experience arose from the recognition that Spriggs’s environmental installation was a space in which to think, dream—and play. It offered an immersion in grey matter but also in the amniotic sac, with plenty of surprises in store along the way, including a huge, hologram-like skull that lunged out from on high and stopped viewers in their tracks.

By magnifying the scale of his work to new immersive dimensions, the artist lost none of the resonance of his previous, smaller-scaled work. Spriggs’s installation was an illusionist’s foray into deep space and darkly prophetic overtones. At times, it seemed like a Claude Tousignant monochrome in 3-D spectral fluorescent green. Spriggs’s sleight of hand led viewers into a distended narrative that taunted us as it evoked a truth at the heart of our image-glutted universe: that we as viewers and voyeurs are complicit in the making of meaning.

This is an article from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art