It is difficult to make an adequate political statement through the medium of art, and more so if it first passes through the lens of deconstruction. David Khang’s videos, installation and performance at A Space issue a challenge to viewers, risking dismissal as absurd while offering a sophisticated reflection on our state of being.

“Wrong Places,” the name of the exhibition, is borrowed from Khang’s performance series Wrong Places / Mauvais Endroits / Lugar Incorrecto / 틀린 장소, which relate to traumatic historical events in several countries.

At A Space, Khang—who is based in Vancouver—presents video documentation from three works in the Wrong Places series. I Have (Had) A Dream, which took place in 2008 in Edmonton, commemorates Martin Luther King’s most famous speech and later assassination—drawing parallels with Barack Obama’s oratory skills, as well as the death threats he received during his 2008 campaign. Once de Septiembre (el otro 9.11 con el tankecito), which was performed in 2008 in Santiago de Chile, commemorates the death of President Allende in the 1973 military coup that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power, aided by the CIA and the Chicago school of economics. And A Measure of War (je me souviens), which Khang created in 2010 in Montreal, addresses Pierre Trudeau’s invocation of the War Measures Act in 1970 in response to the October Crisis.

Khang’s three performance-based videos are projected adjacent to one another, inviting confusion. Headphones are used to access two of the videos.

In the next room, Khang displays one of his main performance props—a “tank” created out of a green plastic tarpaulin draped over a bicycle. (Currently, the tank is adorned with two Quebec fleur-de-lis license plates, one in Korean and one in French. I learnt that this license-plate number belonged to FLQ victim Pierre Laporte.) Also on view is a military uniform—a form of apparel that Khang dons in all of his Wrong Places videos, albeit in different colours.

The performance videos are comical, and also confusing. Throughout, Khang is dressed in military fatigues painted various symbolic colours—like United Nations blue in the Edmonton video—while he conveys classic speeches in unexpected languages.

For instance, in Santiago, Khang struggles to “drive” his tank along the roads to Chile’s presidential palace, surrounded by participatory cyclists and colourful cheerleaders. On arrival, military guards display a mild interest at the “threat.” He begins reading aloud Salvador Allende’s final presidential speech before his death, expressing it in Spanish and Korean. Later, Khang paints his pink uniform copper to symbolize that important Chilean resource.

In Edmonton, portraits of Martin Luther King and Barack Obama are displayed alongside the flags of North Korea, South Korea, Canada and the United States. As Khang recites King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in a public square in Korean, gunmen fire paintballs at him and the portraits. Afterwards, Khang repaints his uniform pink—his website says to reference the term “pinkos.”

In Montreal, on the 40th anniversary of Trudeau’s October Crisis speech to the nation, Khang drove his “tank” to City Hall while clad in a fleur-de-lis helmet and blue uniform reminiscent of the Quebec flag. There, he recited excerpts from October Crisis speeches in French, English and Korean. Later, holding a portrait of FLQ victim Pierre Laporte, he was subjected to more paintball attacks.

The confusion generated by Khang’s works is intentional, and it is linked to Jacques Derrida’s philosophical idea that our experience comprises both “of the moment” experience and “repeatability”—a habitual way of understanding experience. “Wrong Places” contrasts different, almost exclusionary, experiences to allow fresh perception. Derrida discussed democracy and sovereignty, asserting that democratic freedom is really illusory, with sovereignty embedded into the system. The implication is that even democratic countries like Canada and the US have the potential and will to be “rogue.”

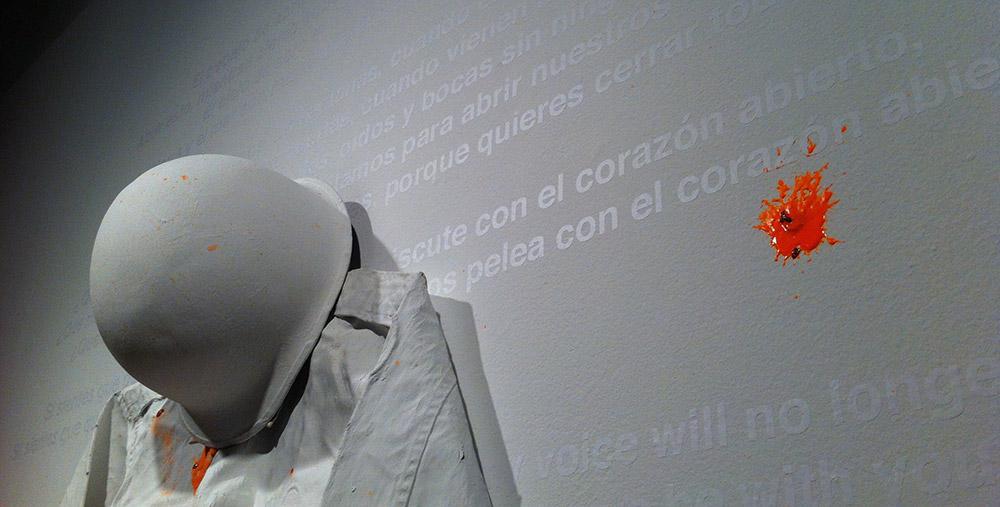

At his opening-night performance at A Space on May 16, Khang marched in white military fatigues. He had a book of Korean poetry and perambulated (not marching) around the room, making eye contact with individuals and reading to them before moving on to take a position against the wall. At that point, viewers were invited to fire paintballs at him. Theatrically, someone in a negligee fired repeatedly at Khang’s groin. (Paintballs hurt.) Later I learned that it was Catherine Chun Hua Dong, a performance artist invited by Khang to participate. Another person took up the gun only to drop it and lapse into sobbing. Khang removed his mask to comfort her, ending the performance.

My overriding impression is that Khang has enormous empathy and is a powerful voice for political art. The “repeatability” demonstrated by the participants also lent credibility to Derrida’s concept.

This post was corrected on June 13, 2014. The original post listed the Korean component of the series title as 틀린 장. In fact, it is 틀린 장소.