“Once Upon a Time in the East,” David Askevold’s retrospective at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, provided a remarkable overview that highlighted the artist’s multidisciplinary practice. Initiated in 2005 by Askevold and Ray Cronin, then chief curator at the AGNS, the exhibition has been mostly developed posthumously by AGNS curator David Diviney since Askevold’s death in 2008.

The first piece encountered by visitors established Askevold’s rudimentary conceptual approach. An early piece titled 3 Spot Game (1968), consisting of a tangle of steel cables and square Plexiglas plates, employed the rules of a pencil-and-paper game called “Sprouts” to bring the sculpture into its final state. The materials Askevold used for 3 Spot Game became uncommon for him afterward, and the rest of the exhibition featured his more familiar use of film, video, photography and computer-generated imagery, but the “game theory” idea was something that resurfaced in many other works employing different processes involving random chance and unconscious decision-making.

Askevold’s works often refuse to make sense upon initial observation. Viewers are impelled to work hard to discover hidden meanings. For instance, his photo/text works are written in a poetic stream-of-consciousness style but sound like instructional riddles, as in this excerpt from Four Notes through a Wall and into the Grass (1974): “Four notes through the wall and into the grass / The notes go through the wall and the grass comes back in / It moves during the day we look at it at night / It focuses at five feet we see at five feet.”

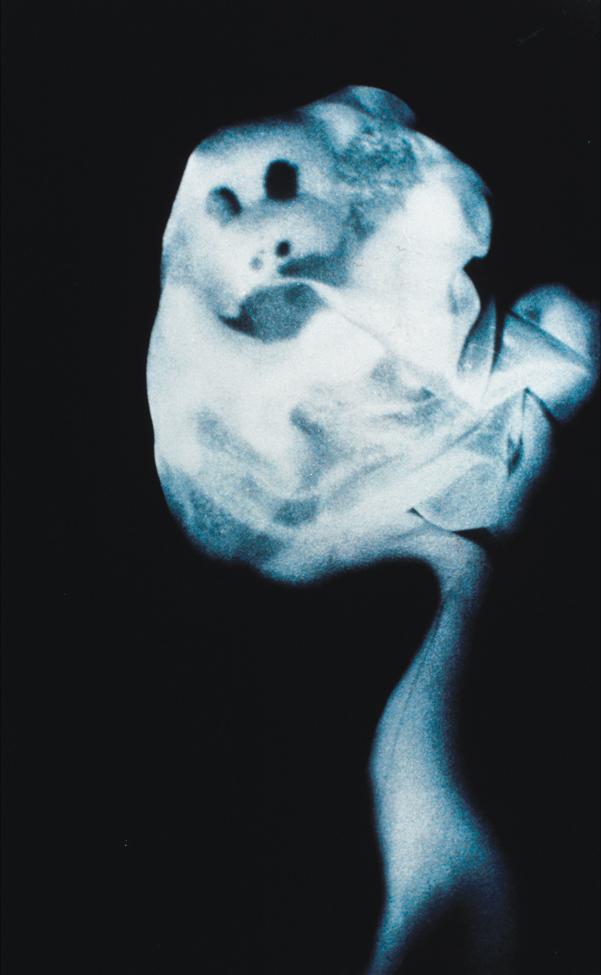

Also included in the survey were two collaborative projects, The Poltergeist (1974–79), with Mike Kelley, and Two Beasts (completed posthumously in 2010), with Tony Oursler. Both Kelley and Oursler were students of Askevold’s during his days teaching at the California Institute of the Arts during the late 1970s, and they maintained a close relationship with him.

The breadth of the show made one want to plan several visits, especially to devote a couple of hours to the video work—which is itself a challenge. Glenn Phillips, who curated “California Video” at the Getty Research Institute, summarized the challenging characteristic of Askevold’s work well in 2012: “If you claim to understand his work you’re probably lying,” he wrote. “His work is not about understanding, it is about not understanding.”

This is a review from the Fall 2013 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents, or buy a copy on newsstands or the App Store until December 14, 2013.