Psychoanalysis and art discourse have had a long and storied relationship. While the meeting of the two is best known to art audiences through the pioneering work of 1970s film theorists Teresa de Lauretis and Laura Mulvey, it was the Surrealists, particularly Salvador Dali, who saw in the unconscious an interior weather system with which to both model and consider portraits, landscapes, actions and texts. Not surprising, then, that Sigmund Freud’s intellectual successor, Jacques Lacan, would find himself conversing with Dali and other artists of that era, at one point becoming Picasso’s personal physician.

Mounted “in conversation” with the Lacan Salon’s Laconference titled “Sixty Years After Lacan: On the Symbolic Order in the Twenty-First Century,” “Crystal Tongue” is organized with an awareness of certain feminist scholars’ dialectical deployment and critique of psychoanalytic methodology, while at the same time offering multifaceted expressions of a female subjectivity resistant to anyone’s “Order”s, let alone the patriarchy’s.

Curated by Amy Kazymerchyk, the exhibition is comprised of five artists—Rebecca Brewer, Vanessa Disler, Tiziana La Melia, Marie-Hélène Tessier and Elizabeth Zvonar—all of whom work in a variety of mediums and, most notably in the case of Disler, are not limited to studio practice. Indeed, it is in the former Exercise gallery that Disler and artist Nicole Ondre opened in December 2011 and closed in January 2013 (adjacent to their studios) that this exhibition, and its related events (weekly artist talks, the launch of an exhibition publication titled DIARY), takes place.

Most apparent upon entering the exhibition is the gallery’s physical transformation. While its structure remains intact (a 400-square-foot storefront with oddly angled walls and the inverted presence of the staircase), Kazymerchyk has painted its white stucco walls a flat black and its floor a dark grey. When considering these preparatory treatments in relation to the gallery’s white ceiling (and dim lighting), what comes to mind, at least for this viewer, are the mediations of structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who, along with the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, were influential in the development of Lacan’s own binary mediations (in the case of Levi-Strauss, for example, black versus white would equal grey).

Another consideration speaks less to the standard white cube/black box division than to the work on display, most of which, apart from Zvonar’s Face (2013), is black and white. Still another consideration is related to Zvonar’s June 22 artist talk, whose title, “godforsaken hole … called … no matter,” brings to mind not only the title’s source (from Samuel Beckett’s 1972 dramatic monologue Not I), but also the writings of a Lacanian scholar known for her positive-space theories of the female genitalia as a system of folds, Luce Irigaray. (It is fitting that this work should appear beneath the inverted presence of the staircase.)

Although the inclusion of colour in Zvonar’s collage-assemblage is eye-catching (bronzed stiletto-heeled pumps, each sprouting a raised single finger, support a John Stezaker–esque photo-collage of a redacted portrait, with an image of the planet Venus at its centre), pride of place is given to Tessier’s This Needs Something More; ’Cause It Ain’t Killing Painting—No It’s Just About Remembering Something Forever About La Sonate de Vinteuil (2007), a 48-by-72-inch black panel dense with the artist’s handwritten French text. How this text forms a narrative is secondary to its registration as unfolding matter, an accretion that, like the unconscious itself, is the result of time, drawing the surrounding work into its vortex but also, in some ways, giving birth to those works, as a universe would a star.

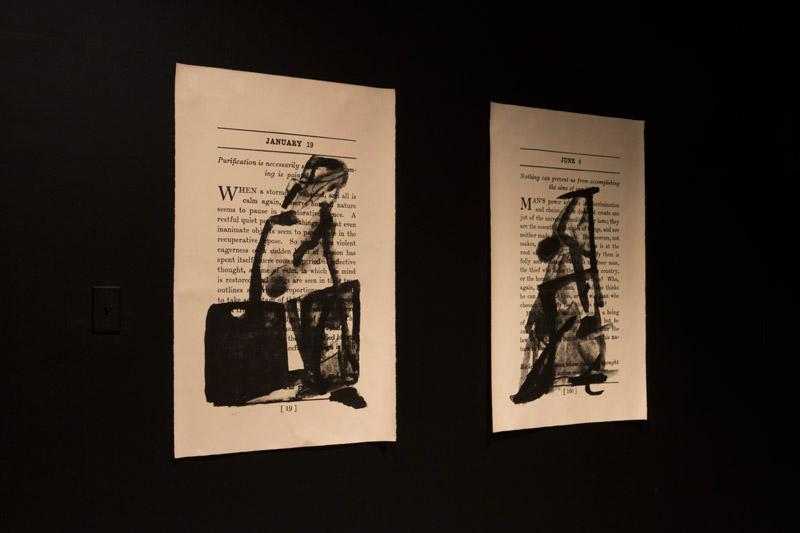

Time is also operative in two excerpts from a recent Rebecca Brewer print series, The Body is the Image of the Mind (I and II) (2013). For this series, the artist has taken a 100-year-old inspirational “book of days” and, on those days that spoke to her, painted over top of them a series of forms and figures. From there, she scanned the pages and desaturated the colour, then blew the pages up to movie-poster proportions. Unlike Zvonar’s redaction of the features that define the face, Brewer’s painted interventions shade her texts, adding a qualitatively different dimension. This appears in contrast to Tessier’s text, which is not applied over a white field, but is scratched out of black acrylic applied to a white surface.

The remaining two works in the exhibition appear in the corner opposite Face—a gridded system of abstract mono prints on the north wall and a painted silk drapery in the gallery’s east-facing window.

Most notable about Disler’s Dream Journal (2012) is the alteration of certain applications that generated its mono prints towards the inclusion of that alteration elsewhere in the grid. Although this is not readily available to the viewer, the grid form itself, unlike Tessier’s handwritten textual massing, initiates the narrative, one that operates beyond the horizontal to include the vertical and diagonal as well. But more so the overall effect is of the schemata we live in, like those static structures Lacan so readily uses to animate his writings.

In Silk Clock (2013), La Melia employs a different system, one that, like Brewer’s shadings, carries its forms and figures within a system of folds—from those suggested by some of its marks to the material presence of the drapes themselves, which fold vertically, as drapes do, but also horizontally on the floor, where the excess material lies bunched. Also worth noting is that the visual occlusions that occur naturally, and perhaps unexpectedly, amidst these folds are mirrored in the artist’s intentional (and supplementary) use of acrylic resist, a “mark” that allows more visible marks to appear fuzzy or out-of-focus, a suggestion not of confusion but of depth.

The first part of the Laconference title refers to the 1953 Rome Discourse, where Lacan (in the words of the conference’s call for papers) “proposed a return to the primacy of speech and language as the fundamental and irreducible concern of psychoanalysis,” something the clinicians and scholars behind Laconference hoped to extend to the visual-art community through talks such as “Desire: Lacan for Artists” by Vancouver Lacan Salon co-founder Clint Burnham. As a further inducement, they invited Lacanian scholar Paul Verhaeghe to speak on the largely unpublished diaries of the late artist Louise Bourgeois, who herself underwent years of psychoanalysis and, upon her death, invited Verhaeghe to study her psychoanalytically self-conscious writings.

While Bourgeois’s life and work would appeal to those who see in “Crystal Tongue” a response to any imposed “Order” (through redactions, scratched-out figure-ground expressions, translucent overlays, time-worn grids, folds and resistances), the unreflexive application of psychoanalytical methodologies to a text is, at least for this viewer, evocative of Freud’s case study of Bertha “Anna O.” Pappenheim (hysteria) and of Lacan’s Marguerite “Aimée” Anzieu (self-punishing paranoia), potentially reducing any subjects (and, in the case of Anzieu, her own fictional writings) to content providers in service of a timeless—and “irreducible”—structure.

This article was clarified on June 14, 2013, with the words “medical subjects” in the final sentence changed to “any subjects.”