A recent visit to “Better with Age: Celebrating 35 Years” at Toronto’s Corkin Gallery left me thinking about the act of looking at photographs: how little they often tell us but how much we are capable of taking from them. The exhibition contains roughly 80 images, representing the better part of photography’s lifespan, but excluding both daguerreotypes and digital photographs. Though the exhibition is structured to lead viewers through the historical, geographical and cultural shifts in the medium, it is, for me, really more about the pleasure of looking at and through photographs, both individually and in relation to each other.

Thinking of Corkin’s 35th anniversary—Jane Corkin was the director and founder of the photography department at David Mirvish Gallery before opening her own photo-centred gallery in 1979—immediately brings to mind the seismic shifts in the relationship between photography and art that were occurring in Toronto (and around the world) during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

It was in 1977 that the Art Gallery of Ontario purchased its first photograph: Arnold Newman’s collage portrait of Henry Moore, to accompany Moore’s donation of works to the gallery a few years prior. Photography-focused artist-run centres Gallery TPW and Gallery 44, founded in 1977 and 1979 respectively, were just finding footholds in the local art ecology, and a young generation of photographers including Edward Burtynsky and Robert Burley were just completing their degrees at Ryerson Polytechnic Institute (now Ryerson University, home to the Ryerson Image Centre, a literal glowing beacon for photography in the city). This was also the time in which Suzy Lake moved from Montreal to Toronto, Arnaud Maggs switched his focus from a commercial practice to art, and Ann and Harry Malcolmson went from primarily collecting contemporary painting to primarily collecting historical photography.

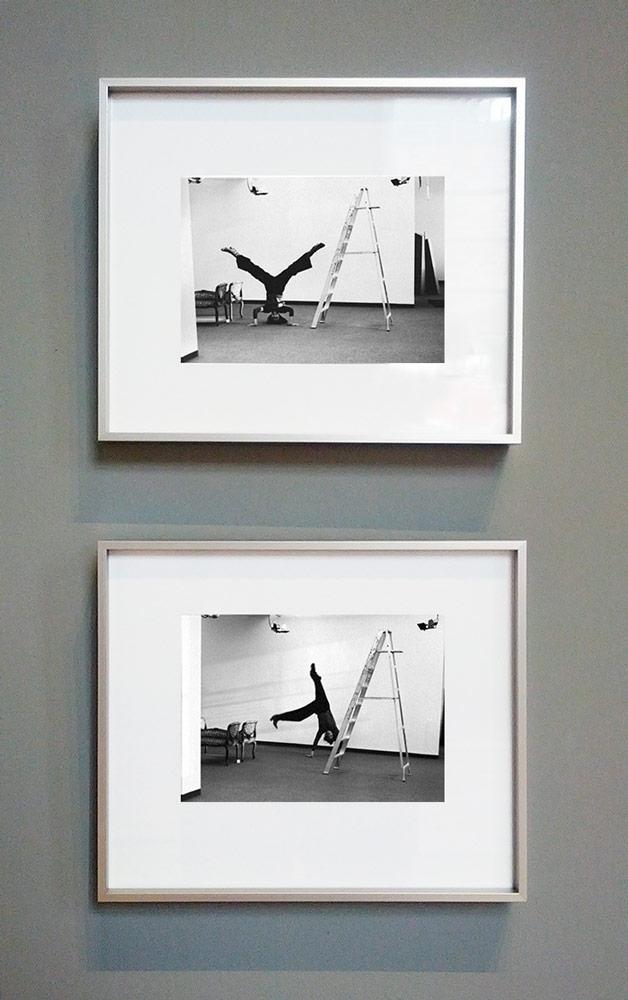

The changing ground around the city surely fostered an atmosphere of new possibilities for engaging with photography and its histories. I would like to think of André Kertész’s candid photographs of Corkin doing cartwheels while installing her first show (two of which are included in “Better with Age”) as a visualization of the anticipation and excitement in the air. It seems that “Better with Age” and a number of other recent exhibitions in Toronto mark a return to and re-evaluation of the energy of and interest in photography as an art object in that time period, which, of course, also marked the publication of then-popular, now-classic studies by Sontag, Barthes and Szarkowski.

Many of these changing attitudes towards the photographic medium are coming full circle. The AGO is currently showing recently donated works from the Malcolmson Collection, one featured more extensively in a 2012 show, “Photography Collected Us,” at the University of Toronto Art Centre. In 2013, the AGO hosted “Light My Fire,” a year-long, two-part exploration of photographs from their permanent collection curated by Sophie Hackett. Yet another categorically similar exhibition was “Curious Anarchy” at the Ryerson Image Centre, curated from Maia Sutnik’s personal collection. (Sutnik herself is largely responsible for the AGO’s photography collection and is the institution’s first curator of photography.)

What all these exhibitions have in common and, for me, what makes all of them interesting, are the ways in which they become portraits of the delightful subjectivities of curators and collectors, in turn becoming a portrait of the viewer in the act of spectatorship. None of the shows is overly prescriptive. Though each has thematic organization, all become about specific people’s relationships to images, images’ relationships to each other and all of their relationships to the viewer.

In this form of photo exhibition there is a unification of photography as a kind of intentional but uncertain cultural artifact. We know each image is likely to exist for a specific reason; at the same time, these images become interesting regardless of their intention or function within the exhibition. The historical works in these shows become contemporary when viewed through contemporary eyes, in contemporary hangings and alongside contemporary works.

For me, “Light My Fire” was an ideal celebratory photography show. Hackett’s engaged exploration of portraiture through the AGO’s collection provided seemingly contradictory messages, overtly asking questions rather than offering answers about the nature of the medium. The show embraced the pleasure of looking while elegantly making viewers aware of the uncomfortable and ethical implications of spectatorship, and of the complexities of representing each other and ourselves. As an exhibition it paralleled the cultural plurality of the photographic medium, employing elements of free association and formal play to allow the photographs to act as catalysts, but also stay grounded in their propositional configurations.

“Better with Age” is a more traditional exhibition. However, its textbook logic, with images sequenced and grouped, is punctuated by subtleties that create an alternate logic.

Unexpected dialogues emerge. Despite being years apart, and across the room from each other, Dora Maar’s Grotesque (ca. 1935) seems to hover over and mock Irving Penn’s Nude 112 (1949–50). Ansel Adams’s Mt. Williamson, Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California (1944), a conventionally beautiful landscape with humanist and environmentalist intent, is implicated in a dirty industrialized vision of manifest destiny through its proximity to four of Margaret Bourke-White’s aluminum-plant photos, and to Penn’s photograph of a deep-sea diver.

These visual cadences and proximate tensions play out in many forms through the exhibition. The silent power of photographs and the subtleties of their arrangement create a temporal flattening. Photographs made throughout the medium’s 175-year history intertwine, speaking to and informing each other, and becoming contemporaries. The slight movements of Corkin’s nearly invisible hand allow form and content to switch places. Surrounded by Bauhaus images, a Horst P. Horst portrait of Salvador Dalí becomes a symbol of European artists fleeing to America during the Second World War rather than a representation of Horst’s innovations in fashion and portrait photography. Margaret Watkins and Constantin Brâncuși seem in close dialogue, while Brassaï and Bill Brandt seem to share the same erotic visions.

There is also the material seduction of historical distance that plays out on the surfaces of many of the images. The most obvious examples come in photographs showing wear, creases and folded corners. I found myself mesmerized by a somewhat dissolved collodion negative by Jean-Baptiste Frenet, mounted on paper beside its salted-paper positive. For me, these excesses of materiality lend an almost pornographic quality to the exhibition’s early photographs.

A striking example of image-as-object is Walker Evans’s Study of African Art 320 (ca 1935). It is a curious image for Evans, part of an (until recently) overlooked series of studies he created when the first African Art exhibitions were being mounted in major American museums. It seems a relatively boring photograph except that it is framed and matted so that viewers can see that it was printed crookedly and full-frame, and bares the marks of the camera’s negative carrier. The inclusion of these small details, regardless of whether or not Evans ever intended for them to be shown, creates a scenario in which the image is wholly interrupted by its own objectness.

As a whole, “Better with Age” and many of the other recent celebratory photography exhibitions create spaces for lateral thinking. Images from a wide variety of sources—art, documentary, fashion, science, advertising, etc.—are brought together on an equal playing field. The canonical and the vernacular merge to speak to the innumerable links between photography and contemporary culture, to how we know ourselves and our histories through images. In many ways this is a daunting (or even undermining) gambit for a dealer, curator, or institution, for it creates a situation in which images lose their autonomy, existing primarily in relationship to each other. It is also a generous one, the strange yet familiar magic and seduction of photography illuminating our many intimacies with images, and their many intimacies with us.