In his fourth solo exhibition at Galerie René Blouin, the Montreal painter Chris Kline explored the ever-changing effects of visible (and invisible) phenomena, with an astute eye for detail and a generous embrace of the ineffable. The two new series on view sensuously occupied an unnameable space replete with grace, thoughtfulness and splendour.

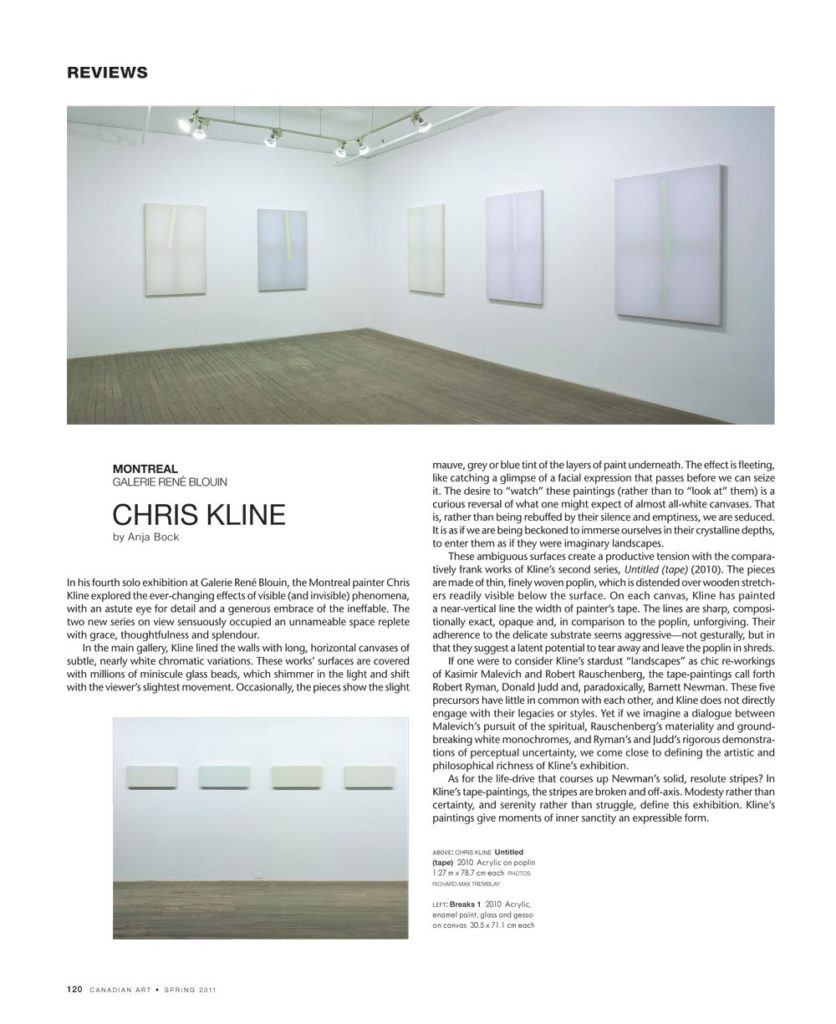

In the main gallery, Kline lined the walls with long, horizontal canvases of subtle, nearly white chromatic variations. These works’ surfaces are covered with millions of miniscule glass beads, which shimmer in the light and shift with the viewer’s slightest movement. Occasionally, the pieces show the slight mauve, grey or blue tint of the layers of paint underneath. The effect is fleeting, like catching a glimpse of a facial expression that passes before we can seize it. The desire to “watch” these paintings (rather than to “look at” them) is a curious reversal of what one might expect of almost all-white canvases. That is, rather than being rebuffed by their silence and emptiness, we are seduced. It is as if we are being beckoned to immerse ourselves in their crystalline depths, to enter them as if they were imaginary landscapes.

These ambiguous surfaces create a productive tension with the comparatively frank works of Kline’s second series, Untitled (tape) (2010). The pieces are made of thin, finely woven poplin, which is distended over wooden stretchers readily visible below the surface. On each canvas, Kline has painted a near-vertical line the width of painter’s tape. The lines are sharp, compositionally exact, opaque and, in comparison to the poplin, unforgiving. Their adherence to the delicate substrate seems aggressive—not gesturally, but in that they suggest a latent potential to tear away and leave the poplin in shreds.

If one were to consider Kline’s stardust “landscapes” as chic re-workings of Kasimir Malevich and Robert Rauschenberg, the tape-paintings call forth Robert Ryman, Donald Judd and, paradoxically, Barnett Newman. These five precursors have little in common with each other, and Kline does not directly engage with their legacies or styles. Yet if we imagine a dialogue between Malevich’s pursuit of the spiritual, Rauschenberg’s materiality and groundbreaking white monochromes, and Ryman’s and Judd’s rigorous demonstrations of perceptual uncertainty, we come close to defining the artistic and philosophical richness of Kline’s exhibition.

As for the life-drive that courses up Newman’s solid, resolute stripes? In Kline’s tape-paintings, the stripes are broken and off-axis. Modesty rather than certainty, and serenity rather than struggle, define this exhibition. Kline’s paintings give moments of inner sanctity an expressible form.

This is an article from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.