There’s a lot to say about the first major survey of iconic late-19th and early-20th-century Haida artist Charles Edenshaw’s work—a show that in its opening week involved not only a five-hour symposium featuring lectures by academics and descendant-artists as well as Haida dancing and drumming, but also a potluck supper in the Vancouver Art Gallery attended by family members.

Indeed, the impressive array of more than 200 pieces assembled from museums, private collectors and family members is not so much an exhibition as a homecoming. While UBC Museum of Anthropology’s 2010 “Signed without Signature: Works by Isabella and Charles Edenshaw,” curated by Bill McLennan, was notable, and the 1967 VAG exhibition “Arts of the Raven” included many of his works (several unfortunately misattributed, as Edenshaw and other artists of his era rarely signed their works), this current show curated by Daina Augaitis and Robin K. Wright of Seattle’s Burke Museum is not only the most comprehensive Edenshaw exhibition to date, but also perhaps the largest solo show of a historical First Nations artist in Canada.

And while the usual arguments about the exhibition’s ethnographic-versus-aesthetic vision can be discussed, “Charles Edenshaw” is much more that the sum of its parts. Just as the man himself straddled the roles of artist and businessman, Anglican convert and Haida chief, keeper of tradition and borrower of new ideas, so does the exhibition blend narrative, visual and anthropological sensibilities.

At times, the gallery itself takes on a sense of sacred space as stories and objects reveal themselves anew in a former courthouse where officials frequently persecuted, rather than celebrated, First Nations people.

Seeing the works up close, rather than in photographs, their aliveness is palpable. Just like the “supernatural beings” Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson (wife of artist and Edenshaw descendant Robert Davidson) showed illustrated on a map of Haida Gwaii in her talk at the symposium, these are not mere objects, but portals into another world.

It was a world gravely challenged, in Edenshaw’s time, by the threat of smallpox, missionaries and other post-contact realities—and yet one that the artist survived by creatively adapting to the new “modernity.”

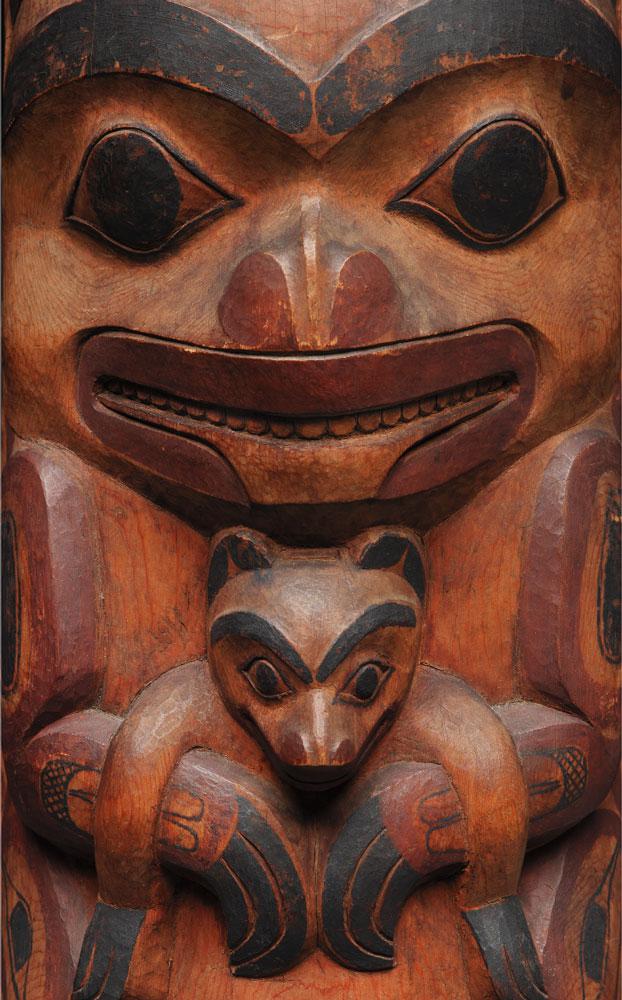

With the potlatches connected to totem-pole raisings and other ceremonies outlawed, Edenshaw produced a series of model and miniature totem poles, houses and canoes for curious anthropologists, which also proved popular with the growing number of tourists. Many of these make up the bulk of the Haida Traditions section that opens the exhibition. The connection between past and present is made explicit via an argillite chest, first displayed at the 1909 Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition in Seattle, whose missing front panel has been remade by Edenshaw descendant and artist Christian White.

Edenshaw was quite literally the “father” of contemporary Haida art—with his descendants including great-nephew Bill Reid, great-grandson Robert Davidson, and great-great grandson Jim Hart—as is made apparent in the Legacies section. But he was also a great innovator and borrower.

As demonstrated in the Narrative section of the exhibition, Edenshaw elevated Haida art to new heights of sophistication. He introduced a perspectival view by layering, thereby increasing the sense of three-dimensionality, and he also developed a more complex narrative sensibility in his work.

This can be seen in a series of argillite platters, rich with stories—like the one about the origin of female sexuality How Raven Gave Females Their Tsaw—notable for its exquisite carving, as well as for its frank subject matter at a time of missionary repression. The stories are augmented by recordings of their recountings by the likes of Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson (who tells the one about the tsaw and notes that it was one of her mother’s favourites).

Other sections—particularly Style, with its collection of spruce-root hats woven by Isabella Edenshaw and painted by her husband Charles, and New Forms—highlight the fusion of European and Haida aesthetics. In her lecture at the symposium, Aldona Jonaitis (director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North) spoke of Chinook art—a term coined by Robert Davidson as the aesthetic equivalent of “Chinook” jargon, the Euro/First Nations trade language that flourished in late 19th century coastal BC.

Details like a four-pointed star on top of a hat, possibly borrowed from the compass of a Boston sailing ship, or the series of canes Edenshaw made with carved handles—de rigeur accessories for the Victorian gentleman, including one that may have been inspired by a London newspaper’s account of Jumbo the elephant—are fascinating and show that 19th-century Haida culture was far from static, an observation that also remains true in the 21st century.

Just as colonial society’s shaming of tattooing and other factors contributed to a new vogue for bracelets bearing family crests, so did Edenshaw’s exposure to European culture result in his very Victorian compotes that manage to communicate powerful Haida iconography even as they read like finely crafted curios. The show includes several terrific examples of crest-based bracelets that were carved by Edenshaw out of melted-down silver dollars, and he also, at anthropologist Franz Boas’s request, created filigree-like drawings on paper depicting tattoos—including a drawing of a dogfish crest tattoo on Isabella’s thigh.

This exhibition rightly shows new Haida art developing as a response to modernity, and it helps situate Charles Edenshaw—some 90 years after his death—not only as a great Haida artisan, but also as a celebrated world artist.