With spring solo shows in Montreal and Toronto and this touring museum exhibition of recent work titled “The Book” (curated by the Carleton University Art Gallery director Diana Nemiroff), Carol Wainio has been getting a lot of attention these days, but the fundamentally enigmatic nature of her paintings will always make them a more challenging read than most. Endearingly, Wainio leads interpretation into wilful disarray. Solid objects segue nonsensically into sensuous brushstrokes of creamy pigment, space seems incoherent and unstable, past and present jostle uneasily, and narrative strands are left to dangle (although her visual quotations from historical illustration tease us into expecting just the opposite). For the viewer, it’s like standing in quicksand—just the way the artist likes it.

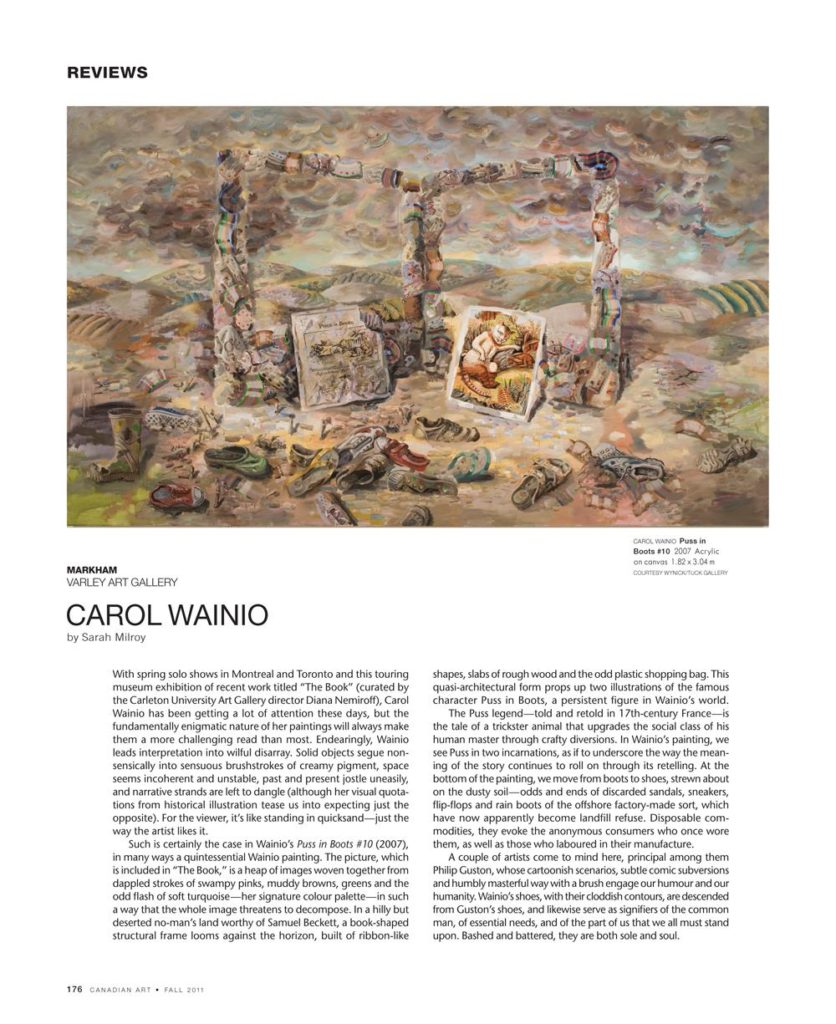

Such is certainly the case in Wainio’s Puss in Boots #10 (2007), in many ways a quintessential Wainio painting. The picture, which is included in “The Book,” is a heap of images woven together from dappled strokes of swampy pinks, muddy browns, greens and the odd fl ash of soft turquoise—her signature colour palette—in such a way that the whole image threatens to decompose. In a hilly but deserted no-man’s land worthy of Samuel Beckett, a book-shaped structural frame looms against the horizon, built of ribbon-like shapes, slabs of rough wood and the odd plastic shopping bag. This quasi-architectural form props up two illustrations of the famous character Puss in Boots, a persistent figure in Wainio’s world.

The Puss legend—told and retold in 17th-century France—is the tale of a trickster animal that upgrades the social class of his human master through crafty diversions. In Wainio’s painting, we see Puss in two incarnations, as if to underscore the way the meaning of the story continues to roll on through its retelling. At the bottom of the painting, we move from boots to shoes, strewn about on the dusty soil—odds and ends of discarded sandals, sneakers, fl ip-fl ops and rain boots of the offshore factory-made sort, which have now apparently become landfill refuse. Disposable commodities, they evoke the anonymous consumers who once wore them, as well as those who laboured in their manufacture.

A couple of artists come to mind here, principal among them Philip Guston, whose cartoonish scenarios, subtle comic subversions and humbly masterful way with a brush engage our humour and our humanity. Wainio’s shoes, with their cloddish contours, are descended from Guston’s shoes, and likewise serve as signifiers of the common man, of essential needs, and of the part of us that we all must stand upon. Bashed and battered, they are both sole and soul.

This is a review from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

A spread from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art

A spread from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art