1. Women in Pieces

There’s a small window between waking and sleeping wherein I often find myself momentarily cast into confusion. Suddenly my bed, body and surroundings feel foreign, as if I’d been mistakenly transplanted into a life that’s beginning to come undone. It’s the nearest comparison I can make to looking at Valérie Blass’s sculptures, which showed at Daniel Faria Gallery early this year. Her works are all odd parts and off angles that confound any notion of figurative sculpture as whole or contained.

Each one offers a tableau (little surprise that Blass has worked in film-set design): a curtain of hair, arm, leg and pair of underwear perfectly sum up the sweeping move of dressing, and while the act is frozen and foreign-looking, it’s still entirely recognizable. There was something about Blass’s figuration that, while subtly disarming, mimicked the way I most often see and think of myself—reflected back in snippets and stolen glances, online and in the flesh.

2. Women on Film

I was endlessly watching women on film this year. Krista Belle Stewart’s Seraphine, Seraphine benefits from an odd contrivance of history: Stewart’s mother starred in a 1967 docu-drama about her life as a public-health nurse in Victoria, which the artist merges with footage of her speaking, some decades later, at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It’s enough to make the work, which offers a necessary exercise in the inability of any image to account for a life, feel a little bit like fate. Joyce Wieland appeared, unannounced, in a film snippet during Michael Snow’s talk at University of Guelph, in perfect keeping with the way her influence routinely creeps up on me. Barbara Loden’s Wanda showed at Images Festival and offered the Platonic ideal of films where bad situations only get worse. The grandes dames of film proper, Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe, held court at TIFF Bell Lightbox in November, finding depth in even the most fallow of fields.

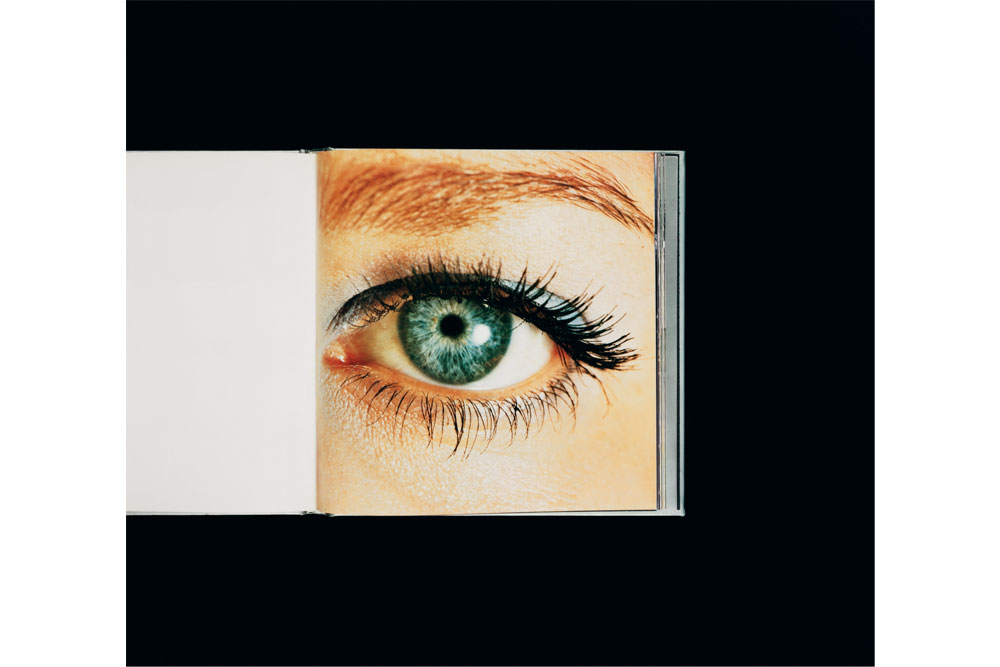

Anne Collier managed to weave many of these impulses together at the Art Gallery of Ontario in her glossy, large-format photographs that chart other images, from celebrity headshots to found pages of self-help workbooks. Her works are all analogue, but they work in a way that feels entirely indebted to the Internet—severed from their original context, they end up free-floating and malleable. This she shares with Blass—it’s a fragmentation that isn’t directly of the digital, but instead feels endemic to it.

3. Women on Reading and Writing About Women

2015 was also a year of reading for me, but of entirely the wrong sort. On the heels of my appointment at Canadian Art I dove back into canonical criticism after a few years devoted to Chris Kraus, Maggie Nelson and Kate Zambreno. I literally carried around a hardcover, 500-page anthology of Martin Amis’s book reviews to page through on lunch hours and coffee breaks.

And then, 11 months or so into the year, I read Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “80 Books No Woman Should Read,” and began reconsidering the company I was keeping. “I believe everyone should read anything they want,” writes Solnit, “I just think some books are instructions on why women are dirt or hardly exist at all except as accessories or are inherently evil and empty.” And while I’d generally gravitated toward fiction books by women writers, this bent had partly slipped by me in non-fiction reading, and in the standards I apply to my own writing.

This was made even more evident reading Claire Vaye Watkins’s “On Pandering.” “I have been writing to impress old white men,” says Vaye Watkins. “The stunning truth is that I am asking, deep down, as I write, What would Philip Roth think of this? What would Jonathan Franzen think of this? When the answer is probably: nothing.” And while I haven’t made peace with, or even fully acknowledged, a similar tendency in my own writing, I haven’t flipped through the Amis anthology since (or my collection of Peter Schjeldahl’s criticism, or Robert Hughes, or, or).

Anne Collier, Eye (Enlargement of Color Negative), 2007. Collection of Randy Slifka, New York. Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York; Corvi-Mora, London; Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles.

Anne Collier, Eye (Enlargement of Color Negative), 2007. Collection of Randy Slifka, New York. Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York; Corvi-Mora, London; Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles.