The relationship between body and self is often expressed in terms more appropriate to the battlefield: “fighting a cold” or “battling cancer.” In “FLUX: Responding to Head and Neck Cancer,” a recent Edmonton exhibition, six artists delivered a powerful, emotional challenge to this way of thinking about both our bodies and the bodies of others. Instead of positioning the body as something separate from the self—something that betrays us—the artists propose new ways of seeing, experiencing and understanding the body in a state of change.

The artists’ work is the result of intimate collaboration with a special group of head- and neck-cancer patients. The artists met these patients through an ambitious interdisciplinary research project called see me, hear me, heal me, an initiative that unites head- and neck-cancer patients, clinicians, researchers and artists to deepen the understanding of head and neck cancer, and ultimately improve the lives of those living with these illnesses.

The interdisciplinary team behind the project includes University of Alberta researchers in departments from surgery to reconstructive sciences to anthropology to visual culture. The artistic team is similarly interdisciplinary, with intermedia artist Kyle Terrance; visual artists Jill Ho-You and Heather Huston; sculptor Jude Griebel; printmaker and professor Sean Caulfield; multimedia artist Ingrid Bachmann; and artist, curator and psychiatry PhD student Brad Necyk. Together, this group and the patients worked to uncover the experience, and express it in ways that would reach beyond the confines of the clinic—offering ways of understanding the body that are not just academic, mechanical, surgical or post-mortem.

“FLUX,” curated by Lianne McTavish and on view at dc3 Art Projects in Edmonton this January, was the first exhibition to result from see me, hear me, heal me. Plans are in the works to travel versions of the show to Seoul and other international locations, and different work stemming from the process behind “FLUX” will open at the McMullen Gallery in Edmonton in late June 2017.

Jude Griebel, Obstructed, 2016. Resin, wood, foam, oil. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Jude Griebel, Obstructed, 2016. Resin, wood, foam, oil. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

At dc3 Art Projects, Jude Griebel’s mixed-media sculpture Obstructed transformed the smaller gallery into a hospital room. A grotesque figure, part man, part mountain, sits on an old-fashioned hospital bed. His skinny arm hangs loosely over his knee as his gaze falls mid-ground. Somewhere around the figure’s throat, a slide of rubble restricts speech, breathing, swallowing. Griebel gives his mountain mobility with traffic that flows across narrow highways, which transect the otherwise stationary mass. The sculpture contains blockage, as its title suggests, but there is also movement and levity.

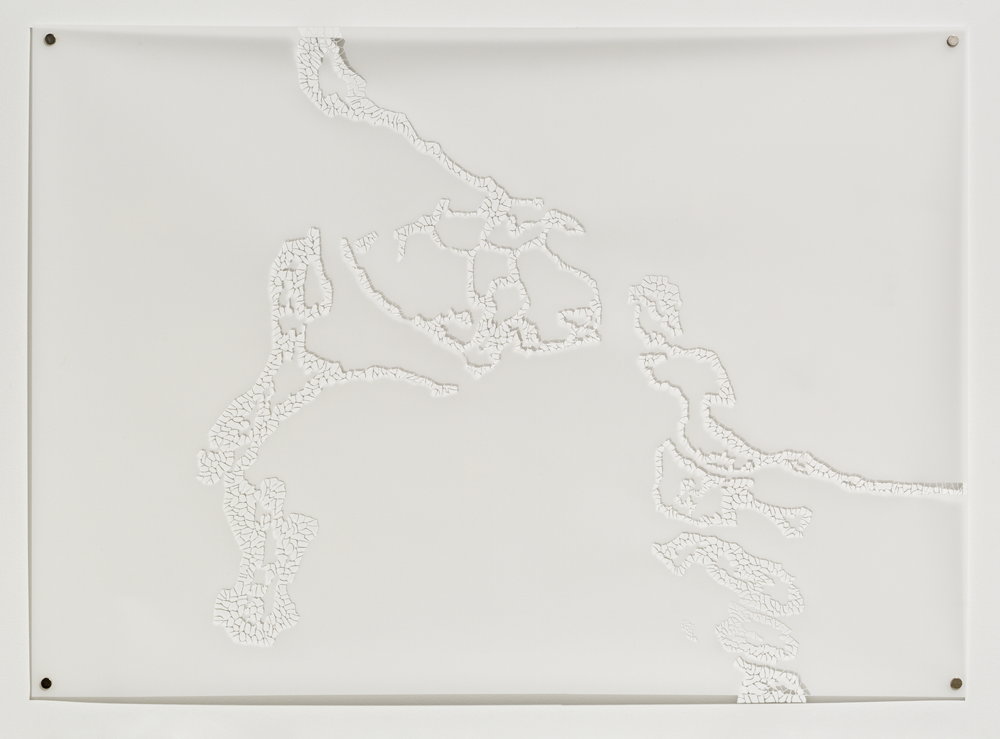

Jill Ho-You, Veils (detail), 2016. Hand-cut mylar panels. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Jill Ho-You, Veils (detail), 2016. Hand-cut mylar panels. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

The view from the bed, should the mountain care to look, is of Jill Ho-You’s Veils. Cut with excruciating precision from sheets of translucent mylar, Ho-You’s Veils depict porous, airy images recovered from patient CT scans. They recall satellite imagery of deltas and fens of fertile landscapes, but their lacy beauty gives way to a sense of unease as the irregular shapes belie their organic, raw origins. An array of dozens of used X-Acto blades line up like tired soldiers on a plinth beneath the Veils. Ho-You found the physical work exhausting, her wrists strained from cutting curvilinear shapes in the stiff mylar. The ferocity of the blades against the fragility of the mylar suggests the sharpness of the pain of a clean cut, but there is strength here, as well.

Ingrid Bachmann, Untitled and Heads (installation view), both 2016. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Ingrid Bachmann, Untitled and Heads (installation view), both 2016. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Ingrid Bachmann’s gouache paintings, clay figures and sound work create a story that takes us from delicacy (her spring flowers trailing from throats opened by laryngectomies) to discomfiture (a red balloon emerges quivering with fluid from an open throat) and then to a hard truth: one large, round, smooth shape and a nearby arrangement of smaller throat-sized shapes form I have something to tell you. The piece emits a staccato, hysterical laugh that morphs into anguished weeping. While the ovoid invites touch, the smaller irregular sculptures suggest another less promising reality: a lump, a growth, a plug.

Brad Necyk, Waiting Room (installation view), 2016. Video installation. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Brad Necyk, Waiting Room (installation view), 2016. Video installation. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Brad Necyk has also included sound in his installation, Waiting Room. Recordings from radiation machines are blended with patient vocalizations delivering a background hum of activity. The sound swells and retreats around Necyk’s groupings of X-ray viewing boxes and monitors. Torn fragments of a patient’s face appear and disappear, keeping the identity of the subject beyond our visual reach. The snippets of faces refuse to form a complete image, creating tension for the viewer, and then forcing acceptance that this is a new kind of identity: something beyond the face-as-we-expect-it.

Heather Huston, I am Wearing Clothes but I am Naked, 2016. Digital print on paper, pencil on vellum, decals on ceramic plates, wooden tree branches. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Heather Huston, I am Wearing Clothes but I am Naked, 2016. Digital print on paper, pencil on vellum, decals on ceramic plates, wooden tree branches. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Heather Huston’s startling images blur her subjects into the background, submerging the face under hand-drawn marks made in a deep blood-red. Arrows trace a path towards the subject’s throat and downward, away from her eyes and mouth. White, clean tables in front of the portraits each feature an incongruous tree branch for a leg. Something is wrong here. Huston positions us in a state of flux, between the expected and the altered.

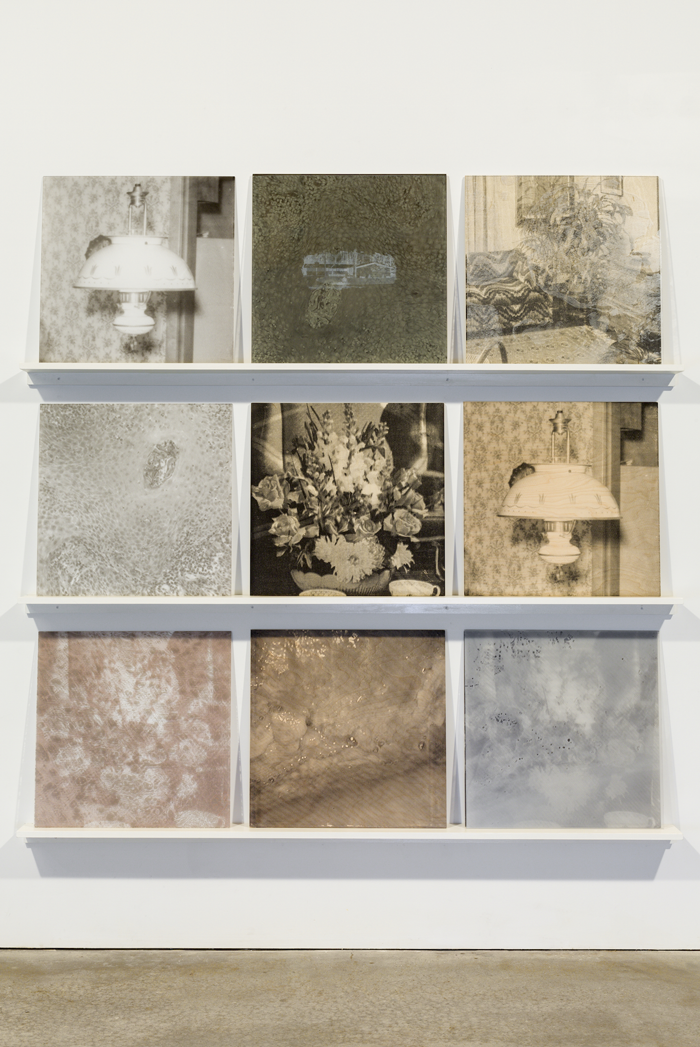

Sean Caulfield, Familiar, 2016. Silkscreen on wood and Plexiglas, with wooden shelves. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Sean Caulfield, Familiar, 2016. Silkscreen on wood and Plexiglas, with wooden shelves. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

A recurrent strategy in the show is the interrupted or filtered view: Ho-You titles her work Veils, Necyk literally breaks up the screen and Huston marks over her subjects. Sean Caulfield’s Familiar is a collection of layered silkscreen prints on wood and Plexiglas. Objects in the images repeat: a wall lamp, flowers arranged in bowl, a cancer cell, a tissue sample. The work has the look and feel of another era, when home was a more predictable space. Caulfield’s mother, Ruth Caulfield, was diagnosed with head and neck cancer when he was entering his second year of university. His work draws on his memory of that time, spent as both observer and participant in the evolution of his mother’s illness and eventual death. Familiar is profoundly moving; even without knowing the personal history involved, I recognized in it an ode to something beautiful, hidden, altered and lost.

Together, these pieces allow us to confront some of the extraordinary aspects of life with head and neck cancer. Patients feel disrupted, frustrated by the breakdown of the normal. But, within these moments, there is strength and resilience—the artists in “FLUX” have realized this, and created something that feels true to another’s experience. Visitors emerge reassured that ways of being in and with the body are as diverse we are. As our bodies change, we change. We are all fluid, all in flux. Perhaps we are not locked in battle with our bodies, but wrapped in a dance, responding to changing tempos and covering shifting terrain.

“FLUX: Responding to Head and Neck Cancer” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

“FLUX: Responding to Head and Neck Cancer” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy dc3 Art Projects. Photo: Blaine Campbell.