This is an article from the Spring 2015 issue of Canadian Art.

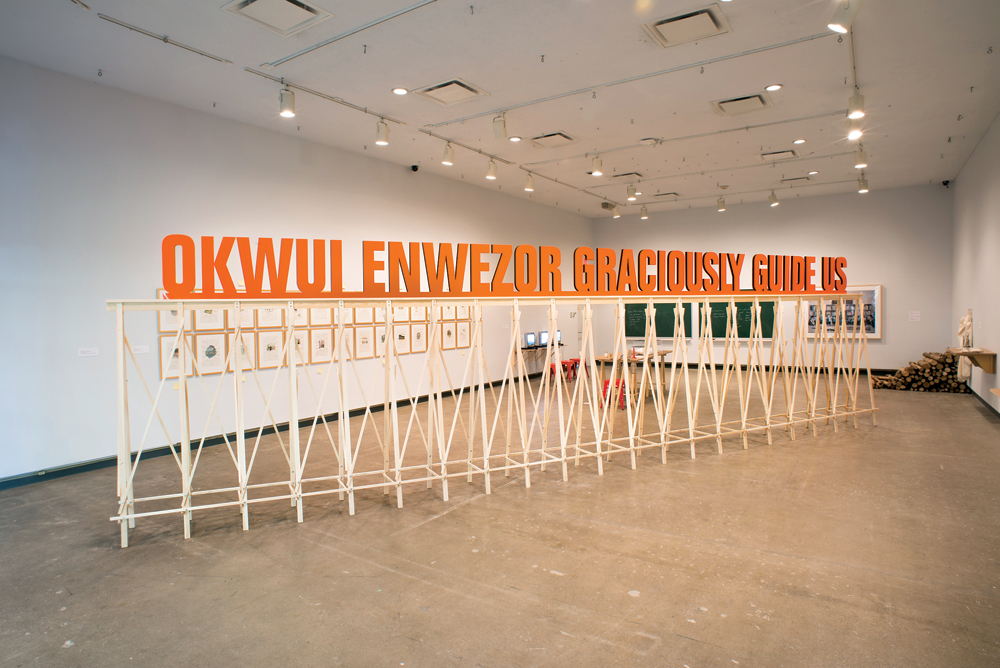

A pine frame inside the Dunlop Art Gallery raised a set of giant orange letters, which read, “OKWUI ENWEZOR GRACIOUSLY GUIDE US.” It’s a life-sized iteration of the type of sign that characterizes Burns’s plastic-domed dioramas of major international art galleries, with outward-facing entreaties to power curators erected on their roofs. Unlike the gallery signage Burns has previously presented in these miniature pleas, or in his photographic projects, Art World Celebrity Signs (2013–14) and Miami Beach Air Banners (2013), which were also on offer at the Dunlop, the Enwezor sign was specifically created for the context of this small gallery lodged inside Regina’s main library. Many of the other works had been previously shown in various iterations, including at Toronto’s MKG127. Here, however, curators Jennifer Matotek and Stuart Reid reframed Burns’s work as being “about longing”: for success, for recognition and for entry into the hallowed halls of the art world (even as he mocks its machinations).

Enticing playful viewers in from the large front window of the gallery, Burns’s curator bobbleheads made an appearance. So did a set of chalkboards that chronicle the art-world figures that have helped and wronged the artist, and those for whom there is still hope. Three video works feature short clips of airport and train-station announcements, calling Burns, Jeff Wall, Catherine David and Beatrix Ruf, and an orderly pile of logs, carved with names of top art-worlders taken from the 2011–13 Art Review Power 100 list, also gesture to the same jet-setting, inexhaustible activities of art’s elite. Together, this recitation of names reads as a set of should-knows: figures that embody the art world’s specialized, insider knowledge. The work first appears to scoff at the ignorance of those for whom these figures are unknown.

But the in-jokes and biting criticism of specialization in Burns’s project go both ways: a series of watercolour illustrations from an in-progress work cataloguing Burns’s interactions with curators, critics, collectors and animals applies strategies of rural, naturalist observation to the behaviours of these artistic celebrities. He recognizes the body language of a kunsthalle director, remarks on a general curatorial fondness for ungulates. In another installation paired with his chalkboards, he chronicles the rituals that have led to him becoming an artist. They are bizarre, incalculable, almost alchemical. They involve milk and honey, and sticks engraved with curators’ names apparently left under the artist’s pillow as he sleeps—a prayer for recognition.

This is the cleverness of reframing Burns’s work as being about longing. Though his art-world references may elude or alienate some viewers, the exhibition is also a play on the nature of exclusive and specialized knowledge. Rather than assuming that Regina viewers will not understand his anxiously specific appeals to characters far outside this Saskatchewan city, Burns performs the simple yet powerful act of enfolding them in his ambitions and, by extension, in a global artistic community.