I am often told that the Internet, like an elephant, never forgets. This is less a truism than it is a rhetorical attempt at behaviour modification: we should, as people who use and like and defend and want the Internet, act as though the Internet never forgets. Yet this does not adequately capture the whole truth about what, if anything, the Internet can be. If the Internet were a single thing—a very large if, but bear with me—it would not be an elephant with an impressive memory. It would be memory itself.

Like human memory, the capacity for the Internet to retain everything is real, and purely theoretical. In practice, the Internet remembers selectively. Our feeds are generated by algorithms that prioritize words signifying good news; the photos we post are of celebrations and other socially gratifying rituals, like birthdays or brunch; we warn each other about clicking on links written in ways we know will inflame or anger us. In the worst parts of the single Internet hive mind, the reverse is true: forums where votes are based on who is the worst, where the most hateful and destructive behaviour is considered admirable, where the point is to constantly be inflamed or angered or to cause such reactions in some other user. But it is the Internet’s ability to retain everything, in caches and screenshots and other digital traces, and then to recall selectively, that makes it most like a human brain, fumbling as it tries to remember whether the front door got locked that morning, or who posted that funny tweet, or where, exactly, a person of interest is geotagged via an IP address.

“Beautiful Interfaces: The Privacy Paradox,” a group show curated by Helena Acosta and Miyö Van Stenis at Reverse in New York until May 14, is an attempt to create new traces for recall outside the monolithic memory of the Internet. In the space, several brightly coloured and aggressively patterned beanbag chairs wait for people to sit with their iPhones and iPads. There is no art physically present. Visitors must log into Wi-Fi networks named for each artist in order to see their contributions, all of which are concerned not with what the Internet can remember, but what it is incapable of forgetting.

“Beautiful Interfaces” asks participants to consider what we give up every time we log on: in its press release, the curators state that “everyday online social practices could look like harmless actions through a naïve eye, but they contain the potential for unexpected consequences when they are traced and connected to algorithmic surveillance systems.” They cite Facebook’s recent adoption of facial recognition software of one such example of ways a seemingly harmless action—having a Facebook account—could lead to the loss of any separation between public and private.

More than just a simple Wi-Fi network, “Beautiful Interfaces” is run on Occupy.here, which was developed by Dan Phiffer for participants of Occupy Wall Street in 2011. As an open-source project for anonymously sharing messages and files, Occupy.here is billed as “inherently resistant to Internet surveillance.” The infrastructure is described as a web island, or a LAN island, accessible only through routers that are not connected to the Internet itself but to private networks. Once visitors have selected the network of the artist they want to view, any page they open in their device’s web browser will redirect to that artist’s work.

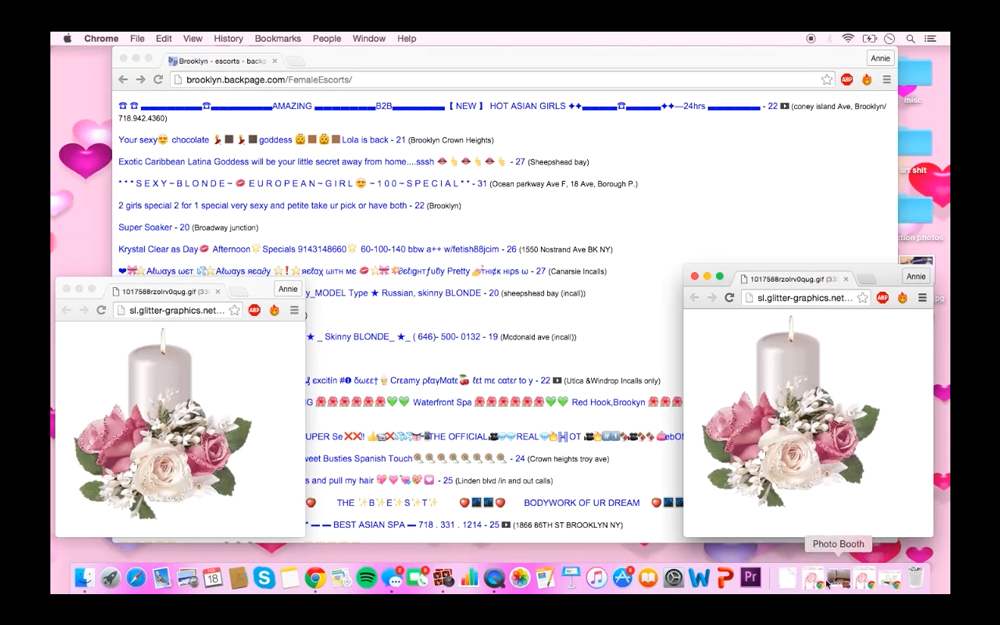

I began with Annie Rose Malamet’s Hooker Meditation Exercise, a video piece that explores her own concerns and experiences with anonymity as a sex worker. Malamet’s digitally modified voiceover begins with shots of New York, snowy sidewalks and speeding trains, as her deepened voice tells us, “Every movie about New York opens with city shots and jazz music. That’s how you know it’s going to be really gritty.” As she scrolls through Backpage ads “New York, New York” begins to play, the exuberant show tune practically bouncing through my headphones. A montage of famous sex workers in film plays: Jane Fonda in Klute, Jodie Foster in Taxi Driver. The meditation exercise itself shows Malamet from the neck down, cross-legged and naked in front of candles, as her voiceover leads us through her thoughts on beauty, weight, fetishes, debt, privacy, anxiety. The ending features the only voices that do not seem to be modified: her former clients, leaving voicemails for her. “Hey beautiful, it’s me,” repeats over and over again, but we do not hear her response.

Carla Gannis’s Electronic Graveyard No.2 shows long rows of cellphone tombstones on a single web page, a video-game figure hovering in front of one such tombstone, as if to remind us that there is no Internet afterlife where good Internet behaviour is rewarded; hell is other, less-secure Internets, perhaps. Heather Dewey-Hagborg, an artist concerned with “biological surveillance,” collects forensic samples abandoned either deliberately or incidentally—strands of hairs, cigarette butts—in order to show what kind of profiles can be made by such everyday ephemera. Here, we review the profile of New York Sample 7, a cigarette butt in her lab which revealed the littering smoker to be a young male, most likely from Central or West Africa, with brown eyes.

From DNA to an equally profitable form of collectible data, I viewed Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc., who calls herself a “data slave” rather than an artist. In 2014, she incorporated her own identity as an “experimental, non-speculative, long-term endeavor,” where she owns all her activity online and as such can bill corporations and other surveillors who would like to use it for their own incorporated goals. Here the curators chose to offer every trace of data Morone generated from their first contact with her about the show until the opening, such as her heart rate (119) and her various text messages (“bread. TEABAGS. Coffee. Chocolate. Red wine. More eggs.”).

Morone is a human made into data; the last artist I viewed, LaTurbo Avedon, is the reverse. In her bio she calls herself a “resident of the Internet,” a digital manifestation of a person that has never existed in our physical world. She is entirely avatar. Her piece, ID, sees her digital form examine her own fingerprints, as a statement on what kind of detection markers her virtual form could provide to the increasingly invasive (and offline) applications of Internet surveillance.

The Internet, by necessity, must be made into a physical thing. To not be able to contain it in some form is like the concept of infinity, or your own faults: the brain can’t face a thought so amorphous and expansive. “Beautiful Interfaces” knows that the Internet would prefer to be made real through physicality, and it is an exhibition that would like to reject that, even if the only solution is to build its own physical alternative through a private network. The paradox here is that, of course, using this alternative leaves its own traces; warnings are sprinkled throughout the final network, a place where visitors can leave their comments and reflections, that any text contributed could be accessible to other visitors as well.

As I watched, and listened, and scrolled, I was already thinking about where I’d be next: how, once I left this Wi-Fi island, would I be able to accurately recall what I had seen? I took notes by hand but ultimately went back through each artist’s networks, taking screenshots, trying to force my feeble human brain to hold on to what it had seen so that when I returned home, to my inland Internet, a trace would be possible.

As a show contained first within the four walls of Reverse and second, in my hand, I did my best to hold on to what I could. I left wondering what I will remember, instead of what I will not be able to forget.

Haley Mlotek is a Canadian writer and editor based in New York. Her work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker and the National Post, among other publications. From 2014 to 2015, she was editor of the Hairpin, and from 2012 to 2014, she was publisher of WORN Fashion Journal.