Collage was one of most fruitful developments in 20th-century art. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque honed it in their cubist phase, when they were exploring notions of mimesis and reality, and playing with trompe l’oeil. The technique then spread like wildfire. Now, more than a century later, collage is still popular, and there is something enduringly pleasurable about it.

In 2009, the Toronto artist Barbara Astman decided to make a collage every day from the morning newspaper. The practice was appealing: choosing, isolating, cutting out by hand, glueing; the negative shapes in the edges trimmed away; the surprising juxtapositions of the bits tossed aside; and then the letting go and moving on with the rest of the day, with the energies of the collage left to waft like sparks from a fire.

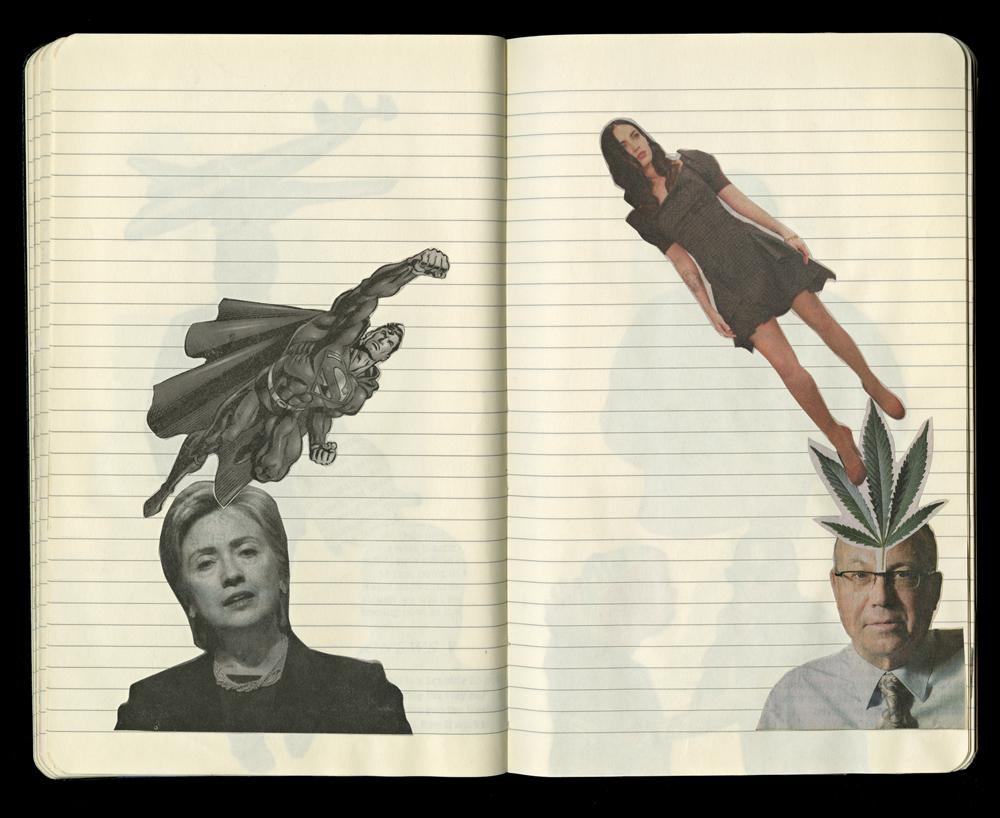

Astman chose to work with double-spreads of a ruled Moleskine notebook, the repeated lines forming a satisfying background, a kind of rhythmic counterpoint to the random, varied grainy newspaper imagery. Taking care to lay down the cropped, flat ends of each image onto one of the four edges of the page, she has imbued the project with a sense of order, as though the rest of each figure or object continues into a space we cannot see; these are tidy collages, not messy compilations. At the same time, the artist did not intend any specific meaning; the works are just fanciful, fun, imaginative combinations: a hat from an upturned martini glass, a leg coming out of a purse, and sudden switches in scale, so that a high heel gives rise to thought bubbles that are diminutive human heads.

Daily Collage (2011) is not without context for Astman, who has always worked with photo-based imagery, and has often drawn from the random particulars of her own life. The quotidian becomes writ large, sometimes literally, as with her 1979–80 Untitled, I was thinking about you…Series, for which she blew up small, square Polaroid portraits to 1.2-by-1.5-metre Ektacolor prints. In the case of Daily Collage, the handheld notebook pages became 90-by-110-centimetre ink-jet prints glazed, framed and hung on the wall. Astman co-opts the viewer to become a kind of voyeur of something that is spontaneous and casual—though created in the face of global catastrophes, as reported in the newspaper.

This is a review from the Spring 2012 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Barbara Astman Collage #3 (from the series Daily Collage) 2011 © Barbara Astman

Barbara Astman Collage #3 (from the series Daily Collage) 2011 © Barbara Astman