Maggie Nelson speculates on a peculiar ache (and the ability to inflict it) in Bluets, her lyrical book documenting a personal relationship with the colour blue. In it, she quotes Goethe: “Every decided colour does a certain violence to the eye, and forces the organ to opposition.” Nelson recounts the days she would work tirelessly at a restaurant where the interiors were “incredibly orange,” only to then return home, fatigued, to dream of her room “in pale blue”—a Goetheian response to orange, “blue’s spectral opposite.”

She writes later, awed, “the eye is simply a recorder, with or without will.” That is: The eye is weak, and its terms of looking are inherently violent. If looking at a colour, constantly, enacts a “violence” on the eye, when a writer sights, registers and describes it by way of language, the aesthetic damage is rebirthed. Ideologically, the act of looking seems akin to an alluring, tiresome confrontation.

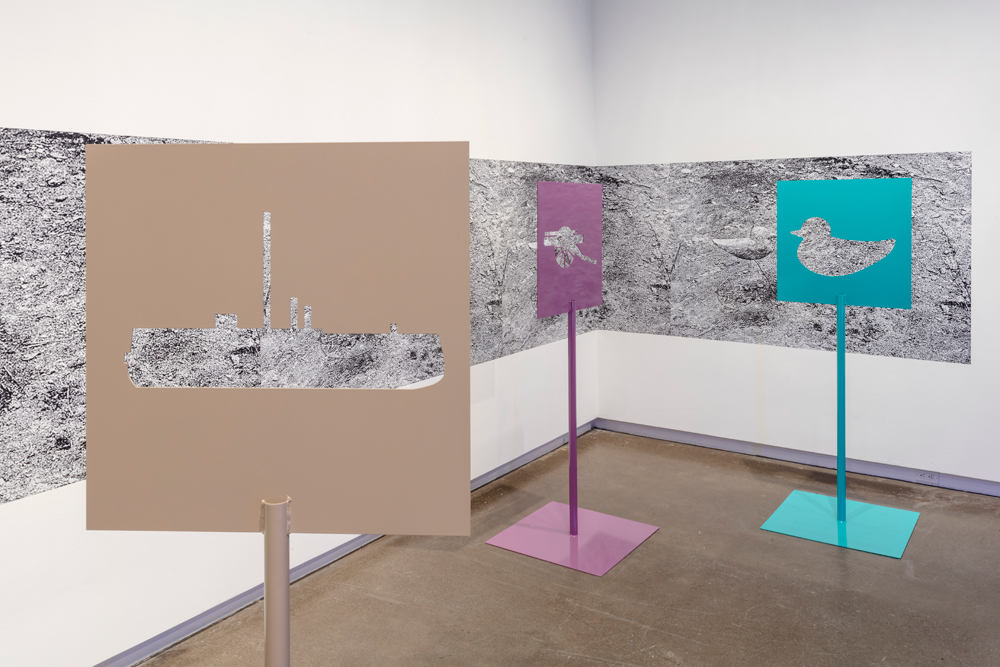

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

But sighting colour is also a crime committed by senses that don’t see—or rather, those that smell, taste, hear and touch (distinctly, slyly). “Prior to the nineteenth century, vision was often attached to touch, taste and sound,” announces the stern voice of Purple, one of the characters and narrators of Bambitchell’s Special Works School—a film that is currently part of their first major solo exhibition at Gallery TPW in Toronto, and is soon to go on view at the Berlinale.

The Gallery TPW show, also titled “Special Works School,” borrows its name from a secret unit of artists created by the British military to conceive and build camouflage technologies during the First World War. This most recent show finds Bambitchell, a collaboration between artists Sharlene Bamboat and Alexis Mitchell, curiously studying the aesthete’s capacity for violence—which is to say, the state’s preoccupation with aesthetics to facilitate surveillance.

Bambitchell, “Special Works School,” 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, “Special Works School,” 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Elements of this exhibition include the video and an installation of sterile tools: three metal stencil stands in shapes of a ship, a cannon and a duck; photographs of two model ducks by late American artist and camouflagist Abbott Thayer; a fake grass carpet; and a glass box filled with sand.

Special Works School, the video, recalls, for me, Nelson’s speculative, melancholic affair with colour in Bluets. The video is narrated by three colours—Sand, Cyan and Purple—who are the protagonists of the narrative, accompanied by a polyvocal chorus that parodies operatic recitative (musical commentary that veers between song and speech). If one were to ascribe genre to the film, the form of epic would adequately address its overarching plotline: the birth, the rise to maturity, then the downfall (to eventual fatality) of Sand.

Sand (swift, warm, coarse, malleable, granular) self-narrates: “[It] begins as most narrators begin, when telling a story about their demise.” The character begins as most narrators begin, nervously, in this case imaging a sun-beaten desert dune. During the course of the film, Sand wets and coagulates; the earthy tint of these images, shot by Portuguese filmmaker Rita Macedo, often gains a mauve temper. An aerial shot of sand trucks is, in one instance, hued in violet, with vehicles laboriously stabbing ground and lifting crumbling mounds of it—moist, raw material to be tossed into glass factories.

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Sand’s “demise” is mirrored in the character’s loss of senses, which decline “until all that (is) left [is] a singular cell.” In Bambitchell’s January 17 artist talk moderated by Toronto artist and composer Christopher Willes, Bamboat revealed the duo’s deliberate choice to have, during the span of the 27-minute narrative, Sand’s voice “electronically disintegrate” and finally become “robotic” in order to mirror the self-effacing, tremulous texture of this substance. For this reason, unlikely pauses and a decaying modulation befriend Sand’s pitch, as inflected by Scottish sound artist and composer Richy Carey, guiding the character from vitality to disposal.

Imprinted as it is with productivity, waste and frailty, Sand is also “omniscient, pansophical, preemptive,” as the character of Cyan (sometimes-green, sometimes-blue, turquoise in the day, oceanic-cerulean by night) remarks. “Sand stands in camouflage, observing. Absorbing. Reflecting light.”

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Tones of sand are ubiquitous in industries that rely on hiding. From desert dune to dark mahogany, its shades have historically been entrusted with camouflage. Developed and implemented between 1997 to the mid 2000s by the Canadian government’s Clothe the Soldier Project, the Canadian Disruptive Pattern Arid Regions camouflage, used in clothing for personnel deployed in desert regions like Afghanistan, embraced sand’s warm tonality.

“A light terracotta colour,” on the other hand, as researcher Keith D. Smith writes in Liberalism, Surveillance and Resistance: Indigenous Communities in Western Canada 1877–1927, was a shade that Indigenous agents, who were hired to closely monitor Indigenous reserve residents in regions of British Columbia during the 1880s and 1890s, were required to “paint all their farm implements” with. “Light terracotta” marries coloration of earth and blood. Sand is a participant here, too.

In Bambitchell’s video, when Sand is nearing death, they declare: “The elimination of my shadow is the essence of my invisibility.”

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

“Colour is often seen as deceitful and authentic, simultaneously,” narrates Purple, their aural command stoic and Siri-like. I’m reminded of Tennessee Williams’s play A Streetcar Named Desire, in which Blanche DuBois, the tragic Southern belle, speaks of camouflage coquettishly. In moments when she is seen, lit unflatteringly, she panics, retreating: “Turn that off! I won’t be looked at in this merciless glare!”

In Streetcar, DuBois fears revealing her age, and relies on an earthy, tender colour texture to offer her lookers a palatable femininity. My first viewing of Special Works School feels punctuated by such moments of desperation, of seeking beauty while nearing the edge.

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, Special Works School, 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In one such instance, a wineglass (chiselled and crystalline, a product of labour and grain) is shot—in the aesthetic of a surround-sound system commercial or an LED flatscreen television screensaver—in close-up and in slow motion. It tumbles to the ground, gradually shattering. “I’m not sure whether the sound comes first or the visual does,” Bamboat tells me over Skype, referring to that instance in the film. I feel more certain; the sound comes first. Its primacy prepares the viewer to assume the role of an eyewitness.

Surveillance incites a particular erotics of self: “Don’t look at me,” the opening line written by Linda Perry for Christina Aguilera’s “Beautiful,” feels ridiculously apt here. For a pop anthem centering a liberal politic of body positivity for women and girls, this line could also contain a desire for camouflage: to remain hidden while also being seen.

Bambitchell, “Special Works School,” 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, “Special Works School,” 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

The surveilled, however, are often denied their terms of being looked at; they are accessed, either “by right or by force,” as Sydette Harry writes in her essay “Everyone Watches, Nobody Sees: How Black Women Disrupt Surveillance Theory.” Surveilled subjects, Harry continues, “either won’t say no, or they can’t.”

Sand, as witnessed by a hushed, spectral Cyan, wants to be seen but not fully regarded. At one point in my viewing, the operatic chorus, evoking the gaiety and musicality of John Greyson’s urgent, rhapsodic 2009 film Fig Trees, attunes and orchestrates: “While Sand tries not to be seen, a spectacle is created.”

When Sand is no more, their overseer, Purple, illustrates this spectacle of death. Towards the end of the film, when the projection leaks a saturating violet onto the walls of the room, I see other viewers’ foreheads, vulgarly lit, the walls drained and complete in a clinical disco tinge. Two white foam mattresses are stationed on the ground before the projection. The foam appears to rise from the ground as Purple bleeds onto us.

Bambitchell, “Special Works School,” 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, “Special Works School,” 2018. Installation view at Gallery TPW. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

It turns out all shades of divine Purple reverberate and plagiarize one another. Voiced by Glasgow’s Mason Leaver-Yap in a BBC documentarian’s Anglo-lilt, this character speaks in 18 Hertz, also known as a “ghost frequency” due to its capacity to induce anxiety in humans. This spillage evokes the desire to both see and mourn—overwhelmingly, erotically, beyond corporeal means—a hue that repeats itself in unexpected, godly ways. It marks the aesthete’s sad, sordid romance.

“But what kind of love is it, really?” Nelson asks herself of the colour blue. She seems to classify it as Bambitchell does Sand: “It calms me to think of blue as the colour of death.”

Bambitchell’s exhibition “Special Works School” is on view until February 24 at Gallery TPW in Toronto. And Bambitchell’s film of the same title will screen at the Berlinale as part of Forum Expanded from February 15 to 25.

Aaditya Aggarwal is a writer, editor and film programmer based in Toronto. He was the 2016 Online Editorial Intern at Canadian Art.