If they awarded Nobel Prizes for the visual arts, William Kentridge would be at the top of the short list. Since his animated South African history films—Felix in Exile (1994) and History of the Main Complaint (1996)—wrested the lion’s share of attention at documenta X in 1997, Kentridge has figured prominently in the landscape of contemporary art. Major exhibitions, like the Art Gallery of Ontario’s “Weighing … and Wanting” of 2000 and MoMA’s “William Kentridge: Five Themes” of 2010, and a series of popular opera productions—Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Shostakovich’s The Nose and this year’s Lulu by Alban Berg—have lifted he and his inventive drawings and animated projections into widespread popular consciousness.

Kentridge is one of the art world’s most notable thinkers on 20th-century history and the human condition. The natural gravitas of his burly, black images wears the burden of representing worlds shaped by apartheid, industrial capitalism and environmental decline. In a notable lecture at the University of Toronto in 2013, sponsored by the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Kentridge held his standing-room-only audience rapt as he PowerPointed his way through a lecture called “Second Hand Reading” based on a Norton Lecture series at Harvard University that introduced a recent series of drawings made on discarded dictionaries and encyclopedias made obsolescent by the arrival of the Internet and quick-search Google and Wikipedia research alternatives. Each phrase and image in the series paraded on a grey, text-dense background that registered as a ready-made metaphor of amounting human language, knowledge and time.

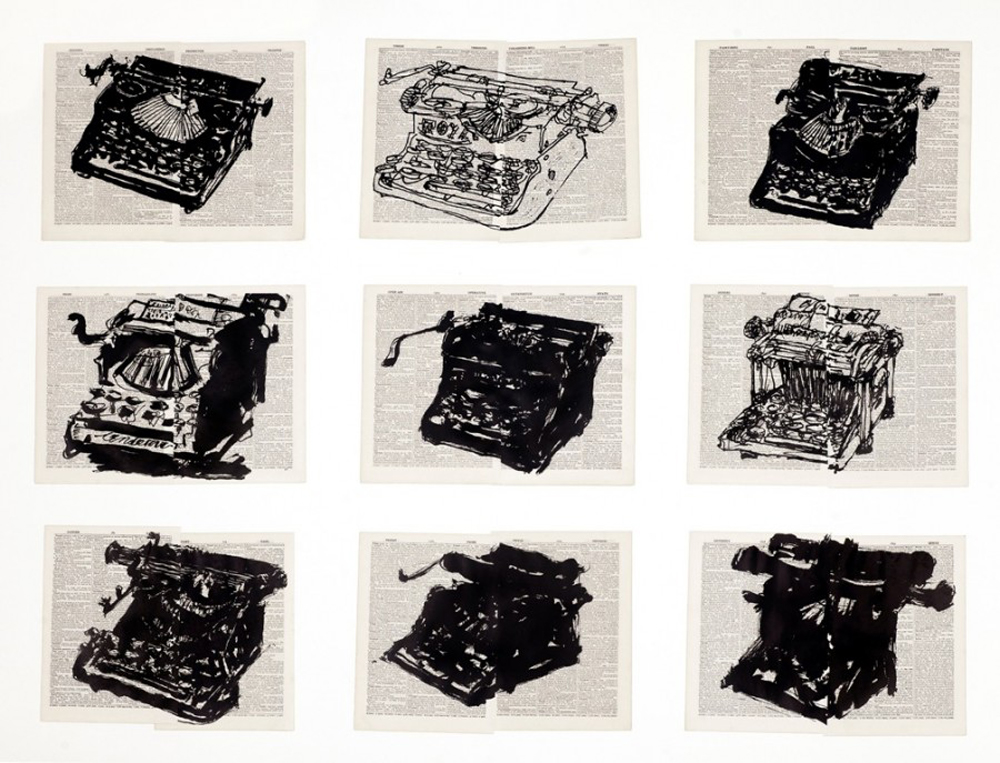

A selection of those works, transformed into the print series Universal Archive, now marks the 6th anniversary of Barbara Edwards Contemporary, which over its short, successful life as a gallery has already hosted two exhibitions of Kentridge as well as other international artists such as Eric Fischl and Jessica Stockholder. Lekkerbreek, one of the largest works in the show, shows a sparse standing tree amid the scrublands of a South African game farm where verticality seems an achievement and the dense trunk cluster of branches testimony to inventive adaption in hard terrain. The pages below include bird illustrations from the Britannica World Language Dictionary that make a fitting extension of context reaching outward to the natural world that holds the tree and inward towards a self-conscious modern awareness of fabrication processes and recycled resources. A similar reflexivity anchors Nine Typewriters, where an archival array of writing machines, from old stand-up typewriters to a sleek portable, sit on top of pages from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Like every other image in the series, it speaks to a thought cluster of effort, alertness and intelligence, whether it is a stretching cat, an espresso coffee pot or a marching woman torn in thirds.