Like the teenager, the comic book’s ascendance into the halls of North American popular culture is a post-WWII phenomenon. Although derided by witch-hunting US senators in the 1950s as a contributor to juvenile delinquency, the comic book is now seen as a legitimate literary genre and is supported by the Canada Council’s writing and publishing program, under the gentrified category of “graphic novel.” How this legitimation came to pass could be told through the life and work of one of the genre’s most prominent practitioners: Art Spiegelman.

Co-produced by the Vancouver Art Gallery, Cologne’s Ludwig Museum and New York’s Jewish Museum, “CO-MIX: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics and Scraps” is the first retrospective exhibition of an artist, writer, designer and educator who has done more than anyone, in any of his generation’s cultural idioms (including rock ‘n’ roll music and sci-fi film), to elevate and advance his genre—both in content and in form. Appropriately, Spiegelman’s achievement is reflected in the exhibition’s title: it’s a play on this irreverent genre’s own self-determined spelling (“comix,” not “comics”) and the inclusion of a hyphen speaks to the means by which this genre’s mediums are composed (according to the exhibition catalogue’s definition, “co-mix” means “to mix together. As in words and pictures”).

And what about that catalogue? While its material arrangement of cover boards, colourful matte pages and quality printing makes for a pleasant object, the minute size and colouration of its text (English in blue, French in black) is, at times, annoying. So too are contributing writers J. Hoberman (former Village Voice film critic) and Robert Storr (ex–senior curator at MoMA), who, in championing both the man and the genre, forsake means for ends: the former has a doth-protest-too-much insistence on Spiegelman’s place in the Modern art canon; the latter offers a cloying personal essay/professional apologia “Of Maus and MoMA,” which is appended to a reprint of his essay from MoMA’s 1991 Spiegelman exhibition. That 1991 text opens with the words “After Auschwitz, to write a poem is barbaric”—one interpretation of Theodor Adorno’s oft-misquoted idea, and a point to which I will return.

The exhibition, curated by Rina Zavagli-Mattotti and coordinated at the VAG by senior curator Bruce Grenville, is mounted on the gallery’s third floor and is organized more or less chronologically in 10 sections. Oddly enough, “CO-MIX” begins with what might be regarded as Spiegelman’s most commercial work—namely, series from his 23-year stint working for Topps, where he started as an 18-year-old and went on to create novelty confections and consumer-product spoofs; his popular Wacky Packages and Garbage Pail Kids sticker cards are arranged in a large floor-to-ceiling grid. Later on is a room full of drawings mainly published by the New Yorker; this display includes a writ-large version of his February 15, 1993, cover that has, in Benettonian fashion, a Hasidic Jew and an African American locked in a kiss—a work made in response to racial tensions in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighbourhood.

Within the rest of this exhibition we find mostly wall works comprised of preliminary and “final” drawings for the artist’s strips and books—some arranged horizontally from panel to panel; others stacked in clusters or in stand-alone frames. A wall-recessed seven-monitor video array impresses in both its installation and its documentation of the artist’s design process, while the floor is taken up with surprisingly few vitrines, allowing viewers room in which to contemplate the many and diverse phases of Spiegelman’s remarkable career.

For those familiar with that career, and with the inclusiveness that a career retrospective implies, a question arises: How might Spiegelman’s earlier, San Francisco–era “underground” works (a period presided over by R. Crumb) “co-mix” with his later children’s books and literacy initiatives? Although no one would expect to see pornographic panels such as “Little Signs of Passion” (from Young Lust in 1974) and the bestial “Shaggy Dog Story” (from a 1979 issue of Playboy) next to works found in the “Kids Comics” section, a restricted entry zone would not be inconsistent with the hand-wringing that often attends the conjunction of children and sexuality. To the VAG’s credit, both eras are equally accessible, albeit at opposite ends of the show, and it is through such spatial distancing that the chronological layout of “CO-MIX” can be rationalized.

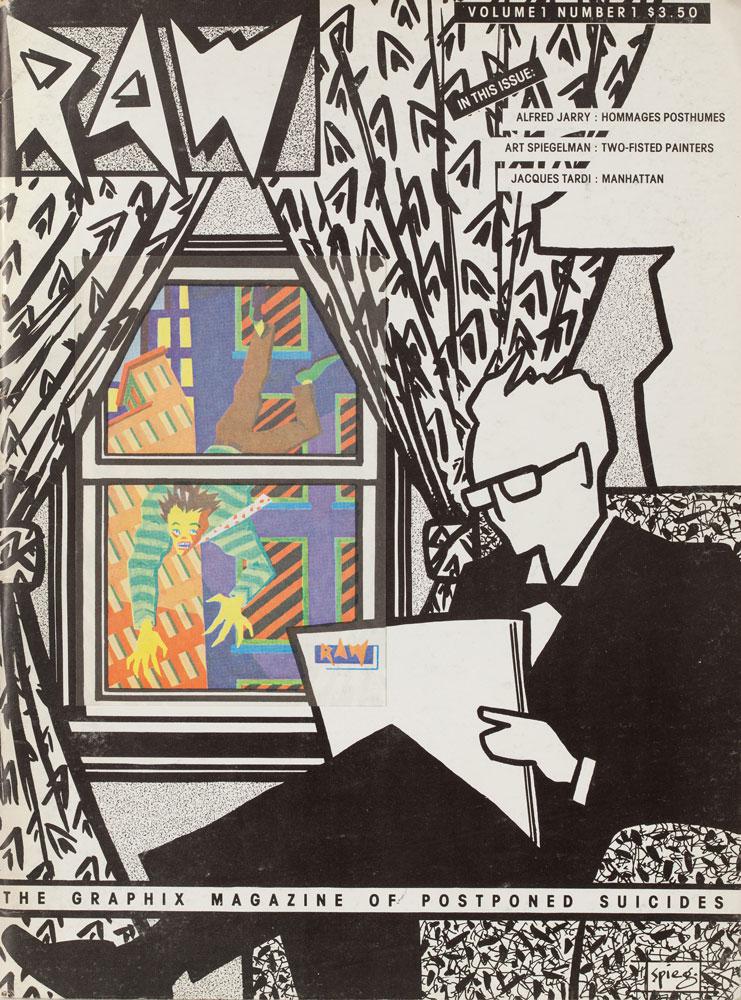

Despite the exhibition’s wide-ranging focus, which includes “Comics on Comics” and “Comic Essays” sections, as well as examples of Spiegelman’s admittedly late embrace of Modernism (Picasso, Cubism, Stein and Joyce) and issues of he and Françoise Mouly’s next-generation-friendly magazine RAW (published between 1980 and 1991), books are what come to mind for most viewers when the artist’s name is mentioned these days. And not so much books he illustrated—like a German edition of writer Boris Vian’s collected writings or a reprint of Joseph Moncure March’s long-lost and debauched 1928 poem The Wild Party—but those he conceived, wrote, illustrated and designed himself. Of those books, 2004’s In the Shadow of No Towers is a more recent example, a project he began after the events of 9/11 (he and Mouly’s Reinhardtian New Yorker cover for that week, black towers against a night sky, is also included). But the book he is best known for, the one that changed the game for Spiegelman’s personal life, his career and the genre itself, are the Pulitzer Prize–winning Maus books, published in 1986 and 1991.

To say that the rectangular space devoted to Maus (the largest space in the exhibition) is underwhelming is an understatement, one that is so disproportionate to the experience of reading Spiegelman’s Maus books as to register, at least upon first entering the space, as a disappointment. But then one might say the same of seeing the film after reading the book, or of a band whose records are great but whose live performances flounder, or indeed, of walking through the gates of Dachau, as I did as an 18-year-old in 1980, my head crammed full of its horrors—only to find a place so neat and spare and orderly one might think it was a rural children’s school and not a high-volume concentration camp. And neat, spare and orderly is exactly what the Maus room is—a place fenced in, as it were, by a horizontal, panel-by-panel display that occasionally carries with it details of its panels’ production.

This Maus display format evokes a relationship between form (death camp architecture) and content (Spiegelman’s parents’ story and his relationship with his father). It’s a type of relationship that was lacking in Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s immersive Documenta 13 installation of Auschwitz victim Charlotte Salomon’s posthumous novel-in-watercolours Life? or Theatre?, and it is also often missing in the socially responsible books-as-wall-works of Allan Sekula. Interestingly, a better parallel for the Maus display format can be found in the Ian Wallace exhibition on the VAG’s second floor, where in taking apart a magazine and laying it out in horizontal stacks, as this post-conceptual artist does with Magazine Piece [Look Magazine, November 18, 1969] (1969/2012), Wallace transforms the reading experience into something akin to architectural viewing.

In his 1975 book Art Since Pop, British art critic John A. Walker attempts a periodization of his era’s genres. After chapters on Op art, Minimal art, Process art, and “Earth, Land and ecological art,” and before chapters on photorealist and monochrome painting, “actions and Body art,” and “Conceptual and Theoretical art,” the critic provides a chapter titled “An alternative to fine art: freak culture.” This chapter describes the sensorium of psychedelic rock concerts, drug-friendly posters and comic books as “content over form” expressions of underground youth culture, with attention paid to “the one undisputed genius of the Underground, Robert Crumb,” a cartoonist whom the critic likens to his generation’s Charles Dickens for his “ability to invent memorable characters” whose “obscene behaviour and violent atrocities… act as a catharsis for his reader’s sadistic fantasies.”

While Crumb’s harrowing upbringing was the subject an eponymous 1994 documentary by Terry Zwigoff, it serves no purpose to compare what Crumb endured to what Spiegelman inherited as the child of Holocaust survivors. Better to compare their paths, with Crumb (himself the subject of a recent career retrospective) emerging as the darker, anti-social anachronistic pornographer who left the US for small-town France in the early 1990s to draw, most recently, The Book of Genesis, Illustrated, and Spiegelman developing as the Apollonian son of Polish immigrants who had long before disembarked freakdom’s magic bus to embrace “a more elegant presentation” of life’s non-fictive horrors (like the Holocaust and 9/11), both as a historian of his genre and a commentator on that which ails our culture.

When Adorno declared that poetry after Auschwitz was barbaric, he was referring not to all poetry but to lyric poetry. Of Spiegelman’s skills, Hoberman notes that the artist’s talents lie less in his drawing style (in contrast to Crumb’s “virtuoso fluency”) than his design sensibility and “intellectual concepts,” which, for this viewer, displays its lyricism less in content than in form—that is, in the various and shifting framing strategies Spiegelman employs to both decentre and propel his tales (an effect Wallace also achieves with his Magazine Piece). Of course, it was Adorno who also said that “Art is the enemy of culture,” and this is where the “vulgar” Crumb and the “genteel” Spiegelman embody competing narratives concerning their genre’s past and future, with Spiegelman eschewing Crumb’s indifferent, fictive shit-storm for a sunnier, more optimistic—and indeed more Modern—result.