The topic of “location” offers a logical starting point for a photography project considering the term’s centrality in contemporary art criticism and curation. Furthermore, the ability to transport a viewer from one location to another is a familiar convention of traditional photographic series. Picking up on these threads, American-based photographers Andrea Robbins and Max Becher presented a talk titled “Transportation of Place” ahead of their most recent show, “Following the Ten Commandments,” at the University of Manitoba’s School of Art Gallery. But in the exhibition itself, Robbins and Becher’s work acquired an instantaneous conceptual sharpness by doing the inverse: bringing locations to viewers from the outside world and into the gallery. This is no small task—requiring the meticulous establishment of a series of signs in each photograph through the specific inclusion or exclusion of particular people, places or things—but Robbins and Becher managed it adeptly.

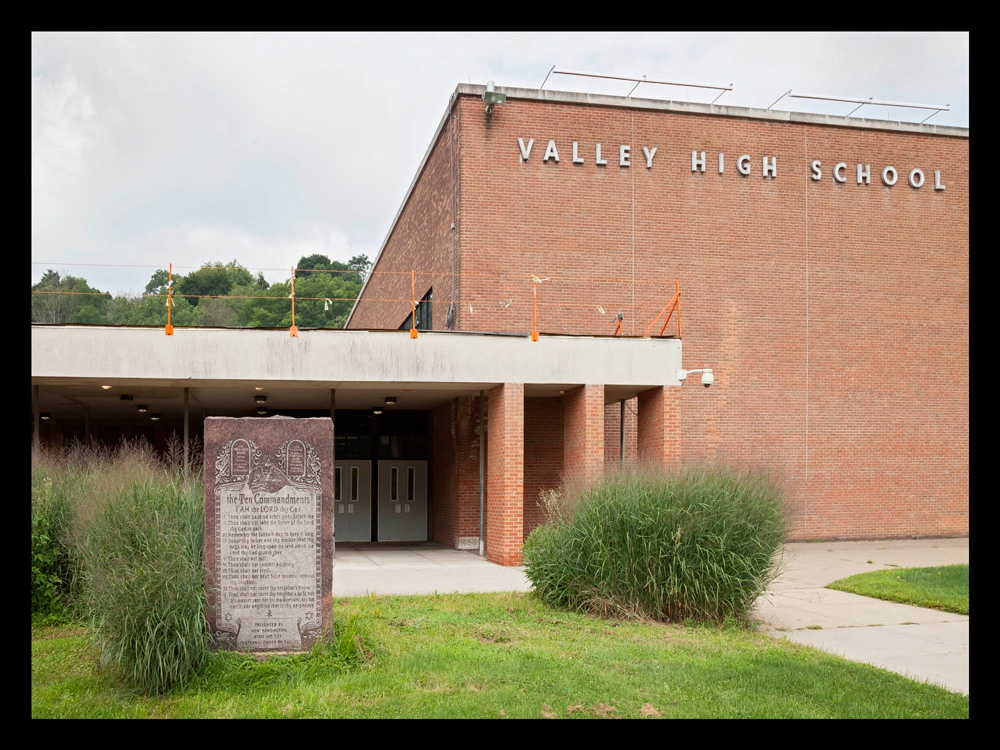

The exhibition consisted solely of 14 large–format images printed on industrial woven-mesh banner that wrinkled off the walls. The photographs are thematically uniform; each depicts a different stone monument engraved with the Ten Commandments sitting in front of a public building in the Southern United States. The artists select buildings that, purportedly, house unbiased activities—county courthouses, public schools, state capitols. The presumption of ideological neutrality afforded these buildings is turned on its head by the placement of the decalogical monuments on their front lawns. The artists deftly reveal deeply rooted religious proclivities within these institutional structures.

The selections made by Robbins and Becher not only allow attentive viewers to establish an imagined place within the photograph’s visual boundaries, but the framing of the images also offers an encounter with contemporary conservative ideology. The photographs supposedly offer unbiased accounts of place, but in the gallery the tongue-in-cheek approach that the artists take when documenting this idea became apparent. The careful inclusion of religious iconography within the photographic frame unravels the impartiality that these buildings represent.

This gesture towards—but ultimate rejection of—truthful documentary photography is interwoven with an emphasis on the neo-conservatism turned radical-xenophobia known as “Southernization,” a term that refers to an ongoing string of Southern-born politicians who brand themselves as equal parts wholesome and intolerant. The popularity of Southernization as a target for criticism amongst liberal pundits seems like a fairly obvious target for the two photographers, and it evinces their ability to cleanly investigate a broader political landscape in a reduced manner. Despite the vast nature of the topic, the photographic style in “Following the Ten Commandments” retains an apparent and intentional cleanliness in all aspects of its execution.

The single detraction from the artists’ conceptual astuteness is, ultimately, their occasionally clumsy and rigid adherence to their own methodological structure. While sticking to a familiar pseudo-systematic means of working may offer an excellent premise to initiate a body of work, the lack of variety within the exhibition occasionally causes some of the images to feel underwhelming, or even boring.

While the provocative subject matter inherently introduces a political slant to “Following the Ten Commandments,” the work denies a documentary interpretation through restraint, instead opting to create an imagined entryway into broader landscape, bringing the political and aesthetic nature of a foreign space into the gallery. This transportation of space is ultimately successful, offering a deeper insight than more expositional activism-based photography would afford.