Who has access to and authority over the archive? How does power seep into, circulate and extend itself through curation of the archive? What do our archives reveal about whiteness, bias and nationalism in Canada—and, depending on how they are presented, what can we learn from them?

These are reflections I mulled over while visiting “Althea Lorraine,” Althea Thauberger’s latest exhibition at Susan Hobbs Gallery. In this project, Thauberger appears as Lorraine Althea Monk, the real-life executive producer of the NFB’s Still Photography Division from 1960 to 1980; Monk created numerous photographic books and exhibitions defining “Canadian” identity during the 1967 Centennial and beyond. (Among other projects, she curated the People Tree installation in Expo 67’s Canadian pavilion and authored the 1968 photo books Call them Canadians and Ces visages qui sont un pays.)

This isn’t the first time Thauberger has inhabited the role of Monk. In her video work L’arbre est dans ses feuilles [The Tree Is in Its Leaves], shown last year at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Thauberger posed as Monk in front of images pulled from the NFB Still Photography Division archive—images Monk was responsible for ushering into the collection in the lead-up to the centennial.

But in “Althea Lorraine,” the artist puts a more focused lens on Monk and the medium of photography itself. Casting video aside, Thauberger presents only photographs here, revealing the medium’s powerful and layered—and never neutral—meaning-making abilities. Also, here the artist presents us not with archival images, but the flipside of those archival images: surfaces that bear the descriptive texts used to classify images within the archive.

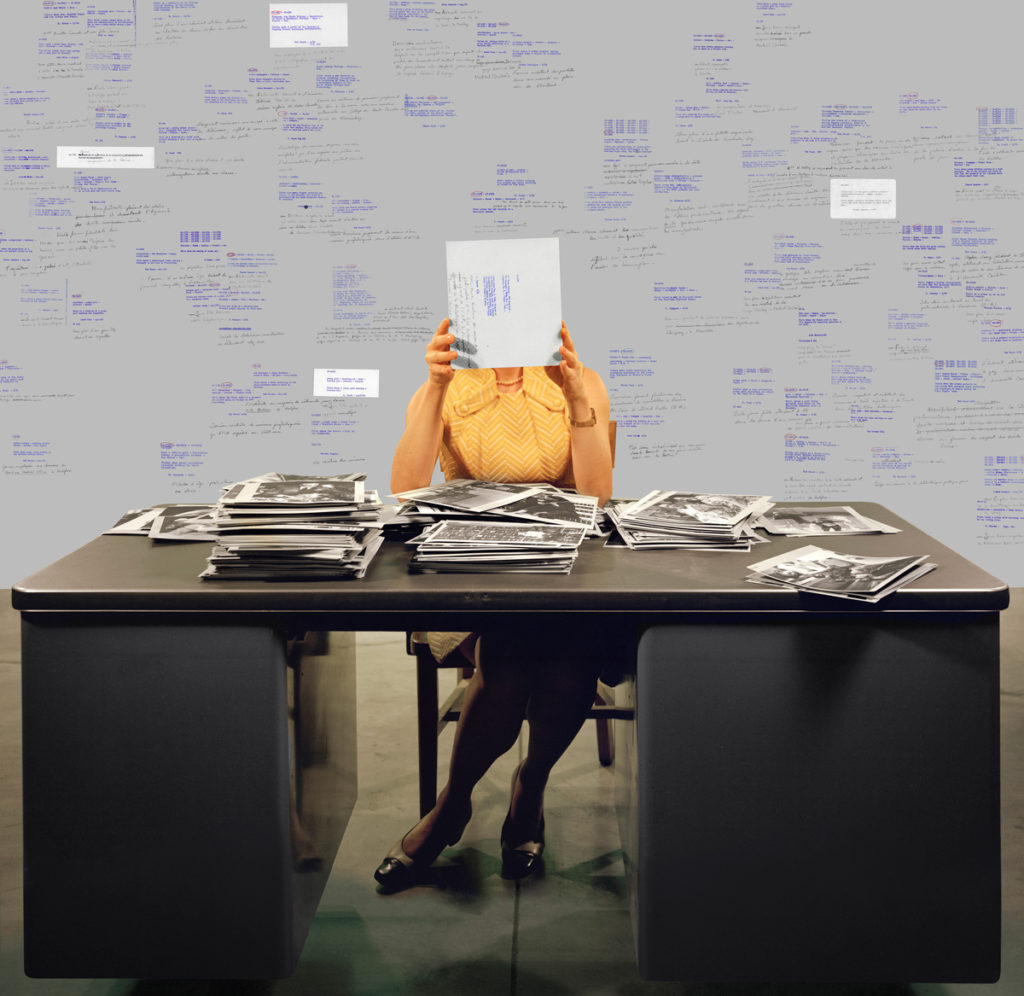

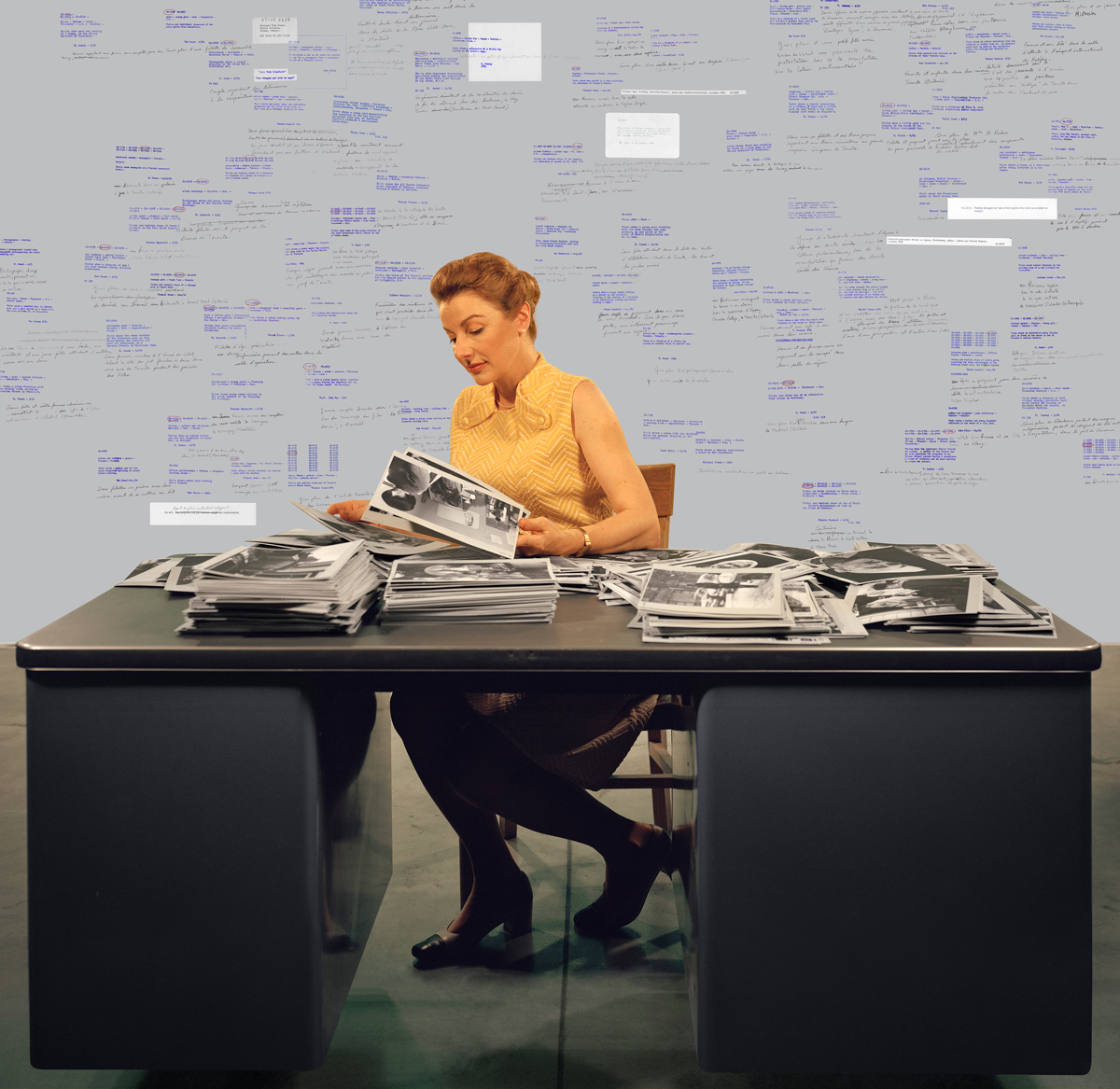

Althea Thauberger, “Althea Lorraine” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Althea Thauberger, “Althea Lorraine” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In the three large colour portraits that greet me in the gallery space—Althea, Lorraine, Index, Nose; Althea, Lorraine, Index, Card; and Althea, Lorraine, Index, Leaf—Thauberger poses as Monk, sitting front and centre at her desk with the written image descriptions surrounding her. These texts, in their profusion and arrangement, are like clouds of mind-maps—or perhaps mosaics, anchored in every portrait by our protagonist.

The image descriptions that surround Thauberger-as-Monk reveal more than the actual images ever could. The texts on the backs of these photographs make visible the bias in the NFB Still Photography Division’s archive—an archive today housed at the Canadian Photographic Institute in Ottawa.

The following captions jump out at me as I peer closer at the portraits: “Photo shows a pretty stenographer at work for the National Harbours Board in Vancouver, B.C.”; “Photo shows a man as he opens his wallet to pay for a newspaper from a newspaper vendor on a Toronto street”; “Photo shows a Coppermine Eskimo girl ensconced with untanned fox pelts at a Hudson Bay post.”; “Photo shows a public health nurse examining the mouth of one of the negro girls at the public school in Lucasville [N.S.].”

All of the images these texts document are dated from the mid-1960s, and the language used certainly reflects the white colonial ideologies of power at the time. Most of the captions do not list people’s names; the subjects’ identities are erased and generalized through description.

These text notations make tangible the assimilative concept of the “multicultural mosaic.” Typically in a mosaic, all elements are meant to be equally important in the final work. However, Monk’s projects within the NFB Still Photography Division, like many Canadian cultural projects past and present, maintained whiteness at their centre. In this biased imaging, whiteness was the glue holding the entire national image in place, seemingly hidden but apparent through the cracks, maintaining the Canadian myth of settler colonialism. (It is no mistake, it seems, that Monk, a white woman, is placed at the centre of Thauberger’s large colour portraits here.)

Althea Thauberger, Althea, Lorraine, Index, Leaf, 2018. Photograph, 152.5 x 157.5 cm, edition 1 of 5. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery.

Althea Thauberger, Althea, Lorraine, Index, Leaf, 2018. Photograph, 152.5 x 157.5 cm, edition 1 of 5. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery.

The revisiting of archives can help shed new light on the past—even if that light is unflattering. Thauberger emphasizes the politics associated with orchestrating an archive, the exclusions it generates, and ultimately seeks to unbury Monk’s aims in her deployment of the photographs.

“What emerged while spending time with this [NFB archive] material was an archive that existed in one part for PR propaganda purposes, and in another, was a way to have a new vision for the purpose of photography,” Thauberger reflected in an interview with the National Gallery of Canada this past summer. Elaborating on the use of photography as propaganda in link with nation-building, she says, “There is a real kind of violence in the reality of producing the imagery of a nation, both physically and psychologically. It’s not a neutral thing.”

Thauberger’s approach in this exhibition prompts a nuanced consideration of Monk, as a white woman in the 1960s in an executive position within a male-dominated industry. The artist manifests a consideration that bridges both critique and empathy, and perhaps, identification: Not only does Thauberger choose to study Monk, she embodies her subject of study as a way to access her work and the archive she architected. Thauberger shares a first name with Monk (Althea) and, when in full 1960s attire with her hair done up, looks remarkably like her subject (a quick Google search confirms this).

In an essay accompanying the exhibition, Lauren Fournier typifies this performative approach as re-performance, stating, “There is something reparative about the practice of re-performing.” A compelling observation Fournier illuminates in her text is that Thauberger’s performance of Monk becomes “this other entity”: Thauberger-as-Monk transforms into Althea Lorraine. Fournier hits the nail on the head here. By means of reparative re-performance, this new persona of Althea Lorraine now has agency to redress and recast the authority that Monk had over the archive.

Althea Thauberger, “Althea Lorraine” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Althea Thauberger, “Althea Lorraine” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

On the main floor of the gallery across from the large colour portraits, there are black-and-white contact sheets of photoshoots where Thauberger poses, again, as Monk. The contact sheets reflect this twinned process of deconstruction and recuperation of an archive director’s legacy. The multiple poses perhaps reflect Monk’s more prideful, constructed, careerist side. Only one specific portrait from these sheets is enlarged and framed on the back wall, and it is titled Art Portrait. Here, Althea Lorraine’s surfacing—a reminder that no photograph offers “the whole picture,” nor any archive the multidimensionality of raw shoot footage—is crystallized.

I circle back to the three large colour portraits, wondering why our protagonist, now surfaced, hides herself from view in the middle image, Althea, Lorraine, Index, Card. Here, Althea Lorraine’s face is obscured by an image she is seemingly observing closely. Viewers are presented with the back of the image. I peer at the small-print caption from the mid-1960s, and it reads: “Photo shows Mrs. L. Monk, Director of the Stills Division, with the District representative, Bert Anderson, during the official opening of the NFB Photo Library at Tunney’s Pasture.” Thauberger creates a meta experience, bringing us back to consider Monk both as architect and subject in the archive, as a person both made visible and obscured by the archive she compiled.

In a fourth and final large colour portrait installed upstairs in the gallery, Althea Lorraine poses upside down, lying on her desk in front of a green screen. Like one of Monk’s archival grey cards reframed by Thauberger, she has been flipped over, and the portrait image is flipped in turn so that she appears right-side-up. She is smiling, almost euphoric—her persona’s achievements, and facade, have finally been exposed for all to see.

Valérie Frappier is editorial intern at Canadian Art.

Althea Thauberger, “Althea Lorraine” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Althea Thauberger, “Althea Lorraine” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist and Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.