When you walk into the Simon Fraser University Gallery these days, the first image you see is a large, backlit transparency of an Asian woman, her eyes closed, standing with her back to a green conveyor belt. In a Canadian context, in a Vancouver context, the photograph reads as Jeff Wall (backlit) meets Edward Burtynsky (factory workers), but Allan Sekula’s Eyes Closed Assembly Line (2010) could not be further from those two photographers’ concerns. The photograph was not made with a medium- or large-format camera, nor was it digitally cleaned up: it’s big but a bit fuzzy, the colours saturated but not eye-popping. The woman’s face, as curator Monika Szewczyk notes in a catalogue essay, is almost angelic, suggesting absorption rather than documentarian truth. Such a complex range of composition, intention and context attests to what interests us in Sekula’s art appearing at this time, in this place.

More on this time and place momentarily, but first a recap of the stunning range of work by Sekula that’s now being exhibited in Vancouver at various venues. There’s This Ain’t China: A Photonovel, illustrating working conditions in a California fast-food restaurant, first created in 1974; two videos from the same period that include, embedded like a jewel, Sekula’s best-known work Untitled Slide Sequence, a 1972 series of workers leaving a factory; The Forgotten Space, a 2010 film co-directed with Noël Burch; the photo series Ship of Fools (1999–2010); and objects from Sekula’s ongoing conceptual project The Docker’s Museum. The first four works are in the SFU’s current exhibition, while the last two are at Emily Carr University’s Charles H. Scott Gallery as part of “The Voyage, or Three Years at Sea Part IV,” which also includes work by Stan Douglas and Uriel Orlow. The Forgotten Space was screened at SFU but can also be viewed at Emily Carr, and additional Sekula works are on view at the Vancouver Maritime Museum.

There are two social—let’s say socialist—dimensions to Sekula’s work here: an attention to labour, its conditions and workers’ exploitation, and an awareness of the role of maritime trade and globalization’s contributions to the further immiseration of workers. There is something both ridiculous and sublime in Sekula’s early work, from the John Belushi–like miming of a pizza restaurant production line in the 1973 video Performance under working conditions (also on display at SFU) to the dignified, humanist portraits of Untitled Slide Sequence. Of the latter, Sven Lütticken has written, “Sekula transforms industrial clockwork time—without denying its hold on people’s lives.”

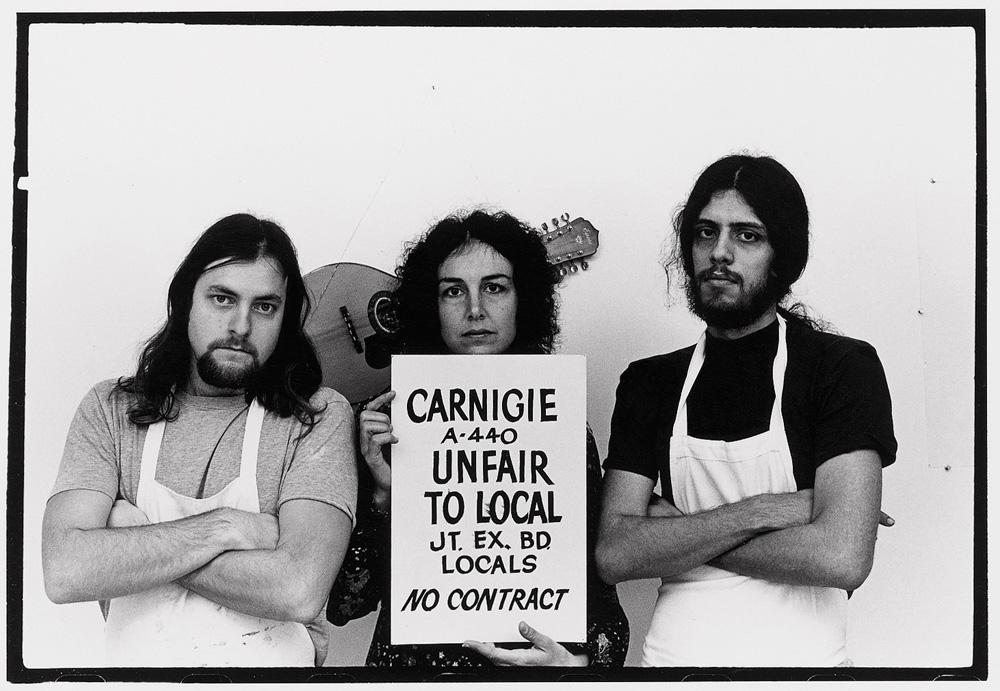

But what is more remarkable is how Sekula’s attention to the social conditions of labour has now extended over a 40-year career, and so what may seem jejune or tendentious (Sekula posing with a rifle in one of the This Ain’t China images) now must be read as a commitment to art that asserts the dignity of workers’ lives and the importance of collective struggle. When, at the conclusion of The Forgotten Space, Sekula calls on seafarers to “seize the helm” of the container ships on which they work, he is calling for transformation at a global level.

But Sekula is an artist, and we must attend to the aesthetic dimensions of his projects in order to realize their full potential. Thus This Ain’t China, as a “photonovel,” offers a number of photographic styles, from socialist heroic poses to garish food porn to noir-like surveillance of the boss’s car. In concert with the backlit transparency that opens the exhibition, such formal variety argues against the artist’s style in terms of consistency as surely as it questions the capacity of any one aesthetic to convey political or social truths.

The installation-like structure of the SFU exhibition also provides a means by which Sekula’s work undermines what may appear to be political dogmatism. The exhibition includes five chairs, on which are booklets in Chinese and English; the texts offer workers’ dreams, rants and grievances, as well as critiques of the veracity of the This Ain’t China images. Appropriating (or prefiguring) museums’ educational strategies and spaces (such as the alcoves and niches in which one finds catalogues, children’s explanations, and visitor surveys), these objects and texts render the imagery less a matter of a static document of exploited restaurant workers and more a provocation, a Situationist-style montage, a Maoist self-criticism.

And here we should close with a nod to the fortuitous timing of this exhibition at SFU, coming during job actions and strikes at the university by support workers in the Canadian Union of Public Employees and teaching assistants and sessional instructors in the Teaching Support Staff Union. Thus an artist’s decades-long project of making visible the exploitation of workers becomes, inevitably, a comment on how that exploitation continues in Canada’s post-secondary educational system. Similarly, This Ain’t China becomes less a comment on shopworn Maoist revolution and more a critique of the globalized conditions of learning from, and looking at, art today.

Clint Burnham is an associate professor at Simon Fraser University and is among a number of faculty who have signed an open letter in solidarity with CUPE and TSSU members.