On opening night of the recent Alison Marks exhibition “One Gray Hair” at the Frye Art Museum, independent curator Miranda Belarde-Lewis announced that history was being made: the exhibition was the first of its kind to bring together a Tlingit curator and a Tlingit artist in collaboration.

As part of this historic moment, a panel of Indigenous womxn took the stage to discuss their professional roles as scholars, artists and curators. Mique’l Dangeli, Caroline Monnet and Crystal Worl joined in dialogue with Marks and Belarde-Lewis. The panel critically broke down modern Indigeneity for womxn: what it means to remain connected to traditional ancestral ways of being and to walk a Westernized world. Each womxn articulated the importance of Indigenous knowledge systems that inform their experience and expressions as artists, scholars, entrepreneurs, apprentices and freelancers. These discussions directly touched on important themes within the show—such as womxn’s resistance against societal norms of beauty, the subjugation of Indigenous artworks as tourist tokens, methodologies of protecting language, and the ways contemporary art is interpreted.

Alison Marks, Nebula, 2017. Leather, sinew. Courtesy of the artist.

Alison Marks, Nebula, 2017. Leather, sinew. Courtesy of the artist.

The exhibition’s opening piece and namesake, One Gray Hair, was titled in reference to Marks’s discovery of her first gray hair. Marks’s voice set the tone for the show, as her writing dominated the wall text of each transdisciplinary piece, explaining the genesis of each painting, print, sculpture or textile. In this narrative, Marks explained the influence of an ancient hair-dyeing method of the Tlingit people, which created a gray hue that the Tlingit considered as a feature of beauty. Conversely, Marks also reflected on her Southern great aunt whose feminine aesthetics were more in line with what many womxn are inflicted with today: a Western expectation of appearing youthful and never aging.

Chemically Tanned also challenged colonial standards of beauty and gender. This piece is a deerskin-casted mould of a feminine body from neck to lower leg, divided in high-gloss blocks of colour intended to represent skin tones. The mould is paralyzed in a sprawled position and, in the show, was mounted to the wall sideways, with small bundles of horsehair strung up and hanging towards the floor. In assembling this sculpture, Marks comments on the prized notion of modesty among the womxn in her clan before colonial contact and how the exploitation of womxn’s bodies, especially Indigenous womxn’s bodies, is so permissible in society today.

Alison Marks, Cultural Tourism, 2017. Installation view at Frye Art Museum.

Alison Marks, Cultural Tourism, 2017. Installation view at Frye Art Museum.

Perhaps one of the most jarring works in the entire exhibition to witness as a Native person was Cultural Tourism. The piece stood alone in a black-box room, spotlighted against the wall with nothing but the white noise of air blowing and swirling between all four corners of the space. The piece consists of an air dancer—one of those ridiculous, inflatable, ambiguous figures often found at new and used car lots to catch the attention of potential customers. This inflatable figure, however, is a totem pole. Its general makeup is that of a white body encompassing traces of formline design in multiple bright colours. Three faces are stacked vertically along its core in different expressions of clownish countenances as the air causes the otherwise inherently rigid structure to jerk and throw its body in uncontrollable fits towards its audience. The repetition of these movements symbolizes the constant reuse of the totem pole in tourism culture. The tall figure suggests social hierarchy to the colonized eye—yet in this appropriated production, it feels like a cheap joke where everyone’s laughing except the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian and other dozens of Northwest tribes who revere these tutelary carvings.

Native people are constantly reminded of sacred monuments and structures that are carelessly replicated for the sake of capitalism and consumerism. Crystal Worl, one of the panelists in attendance at the opening, experiences these corrupt transactions every day as she runs her own business, Trickster Co., with her brother. Trickster Co. sells household objects, sports equipment and street clothing that don fashionable Tlingit Athabascan formline graphics, while non-Native business owners down the road from Worl’s storefront sell totems and other carved objects made in China. For Worl, this mass manufacturing represents a reduction of rich, sacred cultures to tourist-kitsch souvenirs, sold to people who don’t really want them or need them. When settler-colonials put a value on an object, instead of the Indigenous knowledge-makers who intimately know the object’s origins, it is necessary to ask questions: What would be different if our sacred structures could speak? What would be different if people would listen? Our stories fall on the oblivious ears of our colonizers, while also getting lost in translation among our tribal communities.

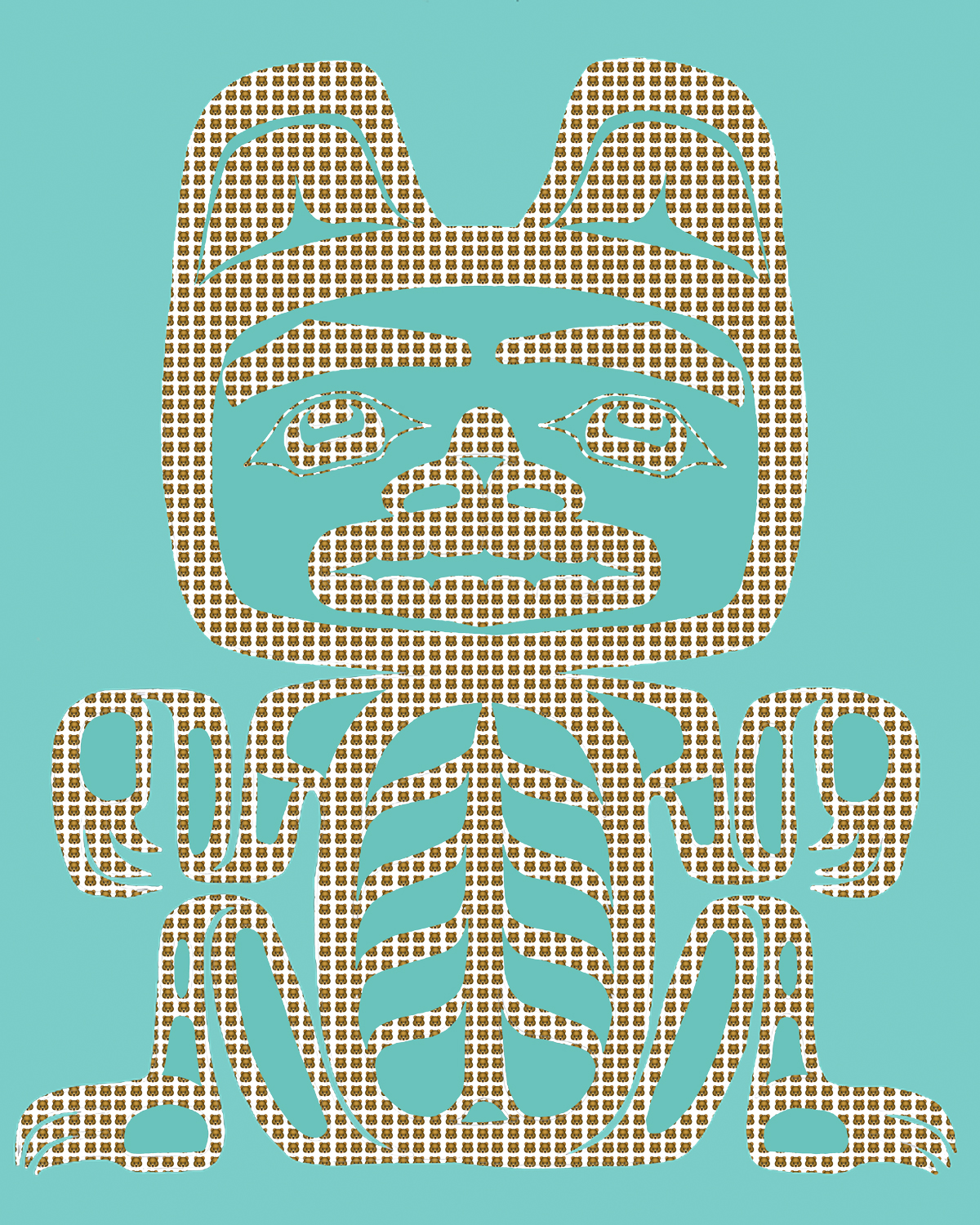

Alison Marks, Bear Emoji, 2017. Digital print on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Alison Marks, Bear Emoji, 2017. Digital print on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Language is a theme that traversed Marks’s exhibition, with emphasis on how communication transference has become heavily digitized. Through emojis, QR codes, smartphone apps/keyboards and other forms of modern media, Native languages have a strong potential of withstanding extinction. However, the harsh reality is that most Indigenous languages are already extinct and the majority of those still spoken, like Tlingit, are critically endangered.

In attempting to immortalize her Tlingit tongue, Marks looked up a free star-naming website and began to name stars in outer space using various Tlingit words and translations. Marks’s star-naming also honoured poet, short-story writer, Tlingit language scholar and advocate Keixwnei Nora Marks Dauenhauer, who is also a relative of Marks. In the piece Heaven and Earth, her chosen star names were positioned within an alien-head shaped vinyl on the gallery wall in black and white. When I stood in front of the piece, I heard the Tlingit words (or stars in the sky) spoken calmly through an isolated speaker suspended from the ceiling, its words uttered low amidst eerie space sounds.

Alison Marks, “One Gray Hair,” 2017. Installation view at Frye Art Museum.

Alison Marks, “One Gray Hair,” 2017. Installation view at Frye Art Museum.

In a similar critical take on language and space, panelist Mique’l Dangeli teaches Sm’algya̱x at ‘Na Aksa Gyila̱k’yoo School in Kitsumkalum, in unceded Ts’msyeen territory. Dangeli recently posted on her Facebook page photos of a virtual teaching session she had with students while she was visiting New York City. The piece speaks to a similar attempt of placing language somewhere far away from us, to be received by someone, somehow after travelling miles, terrains, oceans, generations and light-years away.

The last person on the panel for the opening night of “One Gray Hair” was Caroline Monnet. Monnet is an Algonquin and French contemporary visual artist and filmmaker whose work directly comments on the Native womxn’s experience. Her piece Portrait of an Indigenous Woman is a 16-minute video of 10 womxn (one of them being Alison Marks) defining what it means to be an Indigenous womxn. In one particular testimony, an interviewee explains that “part of being an Indigenous womxn is other people always trying to define you, telling you what you are and what you’re not. I guess that’s also part of being a womxn in many cases. But I find it even more, being Indigenous as well, that people would say I don’t look the way I should look or that they expect me to look… or I don’t know the things that they suppose me to know. So, for me, being an Indigenous womxn is having to deal with that again and again.”

This is a phenomenon womxn experience broadly across gender identity, race and class. However, the lived experiences of Indigenous womxn are marked by complex and various states of unfreedom. Marks, along with the other womxn warriors on the Frye Art Museum stage, shared more laughter than outrage when unpacking the challenges of their existence as one of the most marginalized and mistreated communities on the planet.

Alison Marks, MASK, 2017. Alder, plastic beads, rhinestone chains, faux fur, cotton thread. Courtesy of the artist.

Alison Marks, MASK, 2017. Alder, plastic beads, rhinestone chains, faux fur, cotton thread. Courtesy of the artist.

Despite the dark historical context of many of Marks’s works in “One Gray Hair,” the selection Belarde-Lewis made within this relatively small exhibition allowed for its audience to comprehend the breadth of issues that are all entwined with each other: language loss, sexism, the fusion of traditional and contemporary art forms, and the commodification of 21st century colonial culture. Marks’s work is undeniably graceful and joyful, as revealed by her playful composition of mediums (plastic, vinyl, leather, synthetic fur, rhinestones, mirrors) and colours (neon, metallic, glitter, holographic, galactic and rainbow). Every art piece she presented illuminates Indigenous beauty.

Marks comes face to face with generations of grief—ugly and static—and she challenges the ways in which historical and colonial trauma attempts to break womxn down. Her work confronts what the colonized eye expects to see from a contemporary Alaskan Native artist, yet she graciously shares her Tlingit traditional knowledge and modern reality in powerful and beautiful ways, ways that only a Native womxn could achieve. It was an honour, both in the panel and its exhibition, to witness Indigenous history in such a bright and colourful light.

Hank Cooper is a Cherokee Two-Spirit from Osage Nation territory in Oklahoma. Hank currently works as the Arts Program Manager and curator of the Sacred Circle Gallery at Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center in Seattle.

Note to readers: The term “Womxn” is used in this article to both refuse the suffix “man” and encompass all femme-presenting individuals especially womxn of colour, trans-womxn and all spectrums of womxn-identified groups.