There are six living visual artists whose names swim freely in what remains of the popular cultural mainstream: Yoko Ono, Marina Abramović, Jeff Koons, Ai Weiwei, Damien Hirst and Banksy. Regardless of their merit, these artists contribute greatly to what many of us on the banks of this mainstream think of when we think of contemporary art.

Like Picasso, Dalí and Warhol before them (each of whom achieved similar levels of visibility in their lifetimes), details concerning the early lives of today’s most recognizable artists invariably enter the conversation that determines them, usually in an effort to make sense of their art. Thus it comes as no surprise that Ono’s interest in peace and love is not unrelated to the fire-bombings she experienced in wartime Tokyo. Or that Abramovic’s interest in the body is linked to her soldier mother’s militaristic regulation of it. Or that Koons was a Wall Street commodities broker, Hirst a mortuary worker, and Banksy a butcher.

As for Ai, he seems different. Unlike his peers, Ai arrives both on top of and, paradoxically, underneath that great elephant in the room known to the Western edge of the 21st century as China, a country that, if its governance were to reproduce itself as art, would look less like the largest bureaucracy on the planet than a mainframe computer, the likes of which we have not seen since 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), when its director, Stanley Kubrick, introduced us to HAL.

So it is no wonder that Ai is interested in systems, be they systems of mass production, like the one used to create his Sunflower Seeds (2010), or systems of chance, which, after coming to the United States in the early 1980s, he became known for amongst Atlantic City casino operators, some of whom recognize him as a master of blackjack.

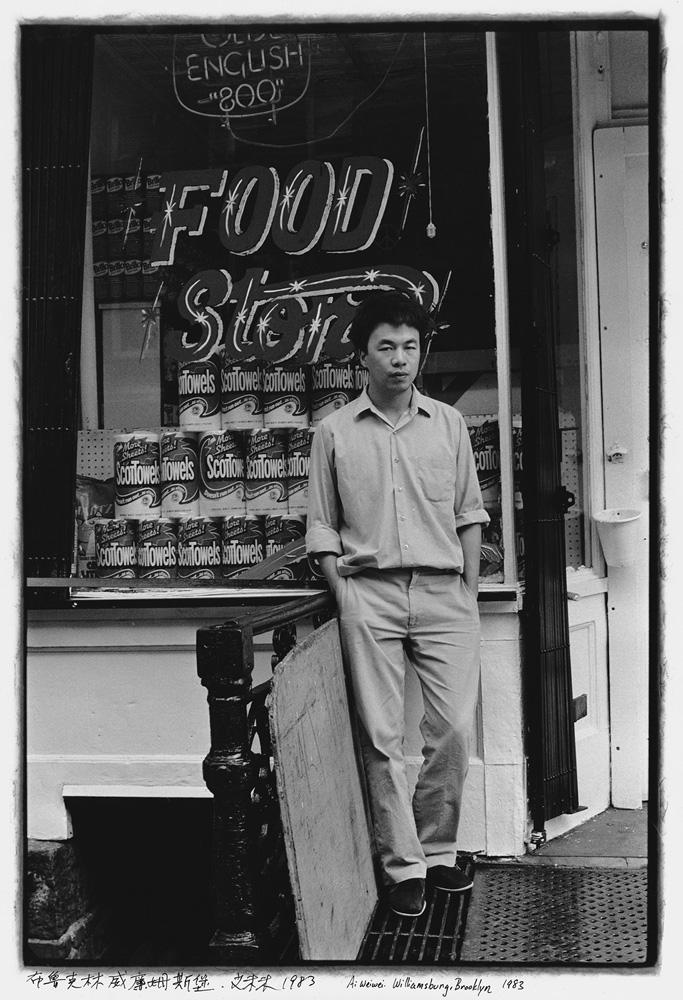

Indeed, it is this first visit to the US that provides the basis for “Ai Weiwei: New York Photographs 1983–1993,” an exhibition of 227 black-and-white pictures selected by the artist from amongst the 10,000 he took (some of which were only recently developed, and some of which were enlarged in sequences from contact sheets) while living in the City That Never Sleeps.

Now at its fourth stop (the exhibition originated at Beijing’s Three Shadows Photography Art Centre), visitors are greeted at the entrance of the Belkin‘s larger gallery by a layout that suggests a left-to-right narrative progression, with pictures running horizontally, one atop the other (mainly due to spatial constraints), an arrangement that the artist-curator condoned, but also one that lends itself to the immersive potential of its array: a world of cardinal points, where east, west, north and south map a decade that bore witness to the consequences of government deregulation, gentrification, homophobia and accumulation in the United States’ largest city.

But not all of Ai’s pictures are focused on “political economics,” nor is his a fascination with a country whose constitution ostensibly supports public protest. For within this narrative exists eddies we associate with civil society: the artist’s recognition of public space, friendships with other artists, some of whom visited him from China, and others, such as Robert Frank and Allan Ginsberg, he met at public events. There is more: from street artists (Ai worked as a street artist when he wasn’t working odd jobs) to documentation of a sculpture he made of Duchamp with a coat hanger and a handful of sunflower seeds—real ones, in this instance, not the 100,000,000 he commissioned some 25 years later when, as an artist imprisoned within his native land, he travelled to a town famous for its porcelain and, in hiring its citizens to make his seeds, raised their standard of living.