We’ve long used needles to alter the feeling of time as it passes. In A Woman’s Thoughts About Women (1858), the 19th-century British writer Dinah Maria Mulock Craik laments that Victorian-era ladies desperately turn to needlework to kill time: “Their whole energies are devoted to the massacre of old Time. They prick him to death with crochet and embroidery needles.” But for the artists featured in Dalhousie Art Gallery’s exhibition “A Very Long Engagement,” involvement with fibre-based processes marks not an attempt to kill time, but rather an exploration of its passing. The show, curated by Frances Dorsey, featured artists—Jozef Bajus, Doug Guildford, Pat Hickman, Dorie Millerson, Sherri Smith and Martha Stanley—who have created labour-soaked works that embody the long and fabled creative histories of their makers.

Hickman measures time’s passage through the work of accumulation and in the transformation of her media. The artist—whose father was a small-town butcher in Colorado—works with uneasy materials such as hog intestine and river teeth. For Ripples (2006), she arranged the undulating carcasses of geckos in a golden blanket of gut casing, confronting the destructive effects of time by finding reconciliation in the creation of order among chaos. In a newer work, Waterline (2013), Hickman skillfully resists the eroding effects of time: “I address issues of the impermanence—the fragility of life—using gut skin wrapped around the river teeth (the last part of the tree to disintegrate), holding that reference to lingering life, holding it together even longer.”

Millerson, a Toronto-based artist, also creates work that illustrates an attempt to “hang on” to moments as they pass. A 2008 work, Car, conjures up generic memories of boxy red cars, featuring a miniature automobile made from needle lace, which references its own materiality by hanging from a spool of thread. Millerson’s intricately detailed car casts a shadow on the gallery wall, as does a nearby miniature needle-lace model of a suspension bridge tethered between two walls (Bridge, 2006). The shadows flicker in and out of focus, evoking the manner by which memories become warped over time, eventually retreating into darkness.

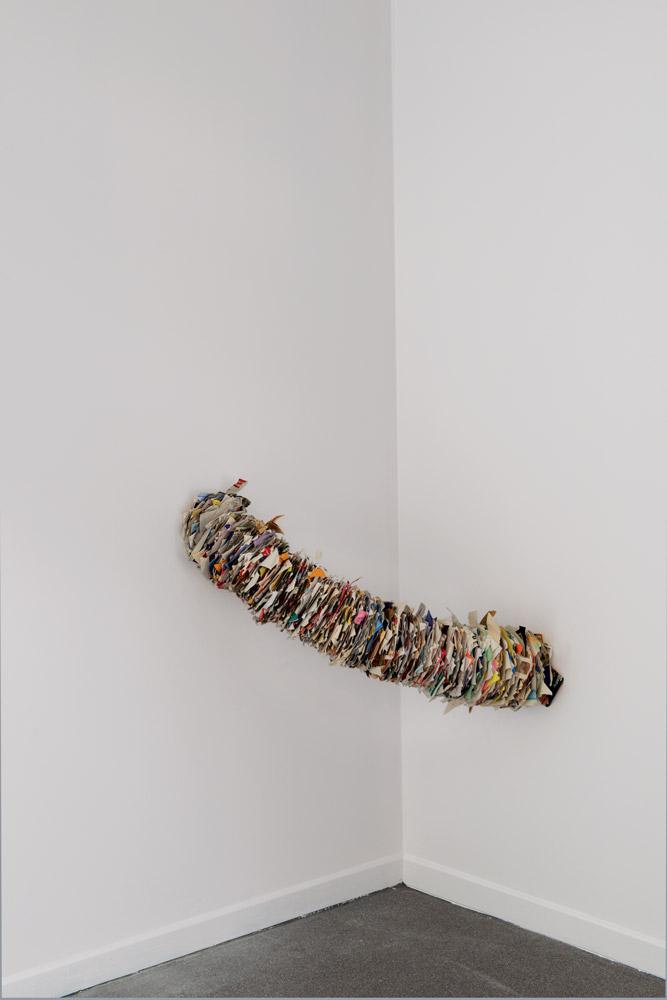

Bajus’s Junk Mail (2006) features crumpled pieces of mail strung together with wire, which ran through three rooms in a horizontal arc. The Slovakia-born artist creates a quantifiable history of chance encounters with junk mail that measures time like layers of bedrock. One can’t help but contemplate the hours upon hours it must have taken Bajus to collect each stratum of mail, and in turn the hours that we must unconsciously spend sifting through junk mail on a daily basis.

The work brought to mind the words of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in his famous children’s story The Little Prince: “It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important.” But for Bajus and the artists featured in this exhibition, it’s not time wasted but well spent, each work referencing life cycles and processes that extend beyond it.

The original version of this review appears in the Summer 2013 issue of Canadian Art, which is available on newsstands now, as well as through the App Store and Zinio.