Walter Benjamin once wrote, “The nineteenth century, like no other century, was addicted to dwelling.” The twenty-first century, however, seems addicted to belonging. While dwelling may occur, in its most essential form, in the physical act of inhabiting, belonging is an intangible kind of ownership—an attachment that moves through and beyond the material, institutional and cultural places we dwell. Social-media platforms attempt to locate it in networks of followers. Airbnb implants users in the homes of others. Even the isolationist and nationalist movements that defined the political landscape of last year—in the chant “Build that Wall” or the T-shirt slogan “Fuck Your Safe Space”—depicted a desperate urgency to spatially achieve belonging, if only for a few.

While inevitably relying on the fatigued concept of “home” as extending beyond the studs supporting a physical structure, three recent exhibitions in Toronto underline how architecture often obstructs our desire to belong. Each show dismantles the notion of “dwelling” brick by brick.

“Where is Home?,” curated by Zviko Mhakayakora at Xpace Cultural Centre, is perhaps the most literal call to situate this rootedness. In a show focused on home—attempting to locate belonging after migration, displacement and conflict—there are few, if any, inhabitable environments.

Maxim Vlassenko, Coming Home (still), 2016. HD video. Courtesy Xpace Cultural Centre.

Maxim Vlassenko, Coming Home (still), 2016. HD video. Courtesy Xpace Cultural Centre.

The spaces recorded in Maxim Vlassenko’s video Coming Home, for instance, contemplate a personal history of immigration to Canada from Kazakhstan, and therefore, are more suited to migrating than dwelling. Streets, bridges, slides and trains are all empty vessels, places to be with others—but only momentarily.

Vlassenko’s migratory spaces recall the Canadian Pacific Railway, the iconic nationalist infrastructure that bound the country together—Atlantic to Pacific—as a settler project. It materialized belonging for a select group, which was only achievable through a physical structure of an immense scale. Seemingly benign in its agency, the railway was as much about inclusion as exclusion—joining the material (agencies, resources and economies) and severing the immaterial (cultural inheritance, rootedness and the possibility of re-situating them).

Tings Chak, His House, 2011–16. Mixed-media installation. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Tings Chak, His House, 2011–16. Mixed-media installation. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Tings Chak’s installation His House in “of movement and dwelling,” curated by Farah Yusuf at Trinity Square Video—another exhibition unmaking housing—questions the foundation of this sprawling edifice of the railway, and its relationship to belonging.

Chak reimagines the home of a Chinese indentured worker, one of more than 17,000 who migrated to build the railway, immortalized in an archival image from Montreal’s McCord Museum—its shadow or echo traced by a thin black line.

Displayed inside this hollow, spectral dwelling are additional archival photographs from which Chak has surgically removed the figures of railway workers before coating the images with a layer of semi-opaque vellum. These ghostly inhabitants critique the celebratory image of the last spike, absent of the workers who gave their lives traversing the Canadian landscape, casting the railway as an intergenerational monument of unbelonging.

For Chak’s subjects, home appears as a lost object—severed by physical and institutional structures—that one can never return to or locate. “Who can foretell when I will be able to return home?” reads a translation of Chinese writing carved in 1919 on the wall of a Victoria, BC, immigration building the artist transferred onto vellum.

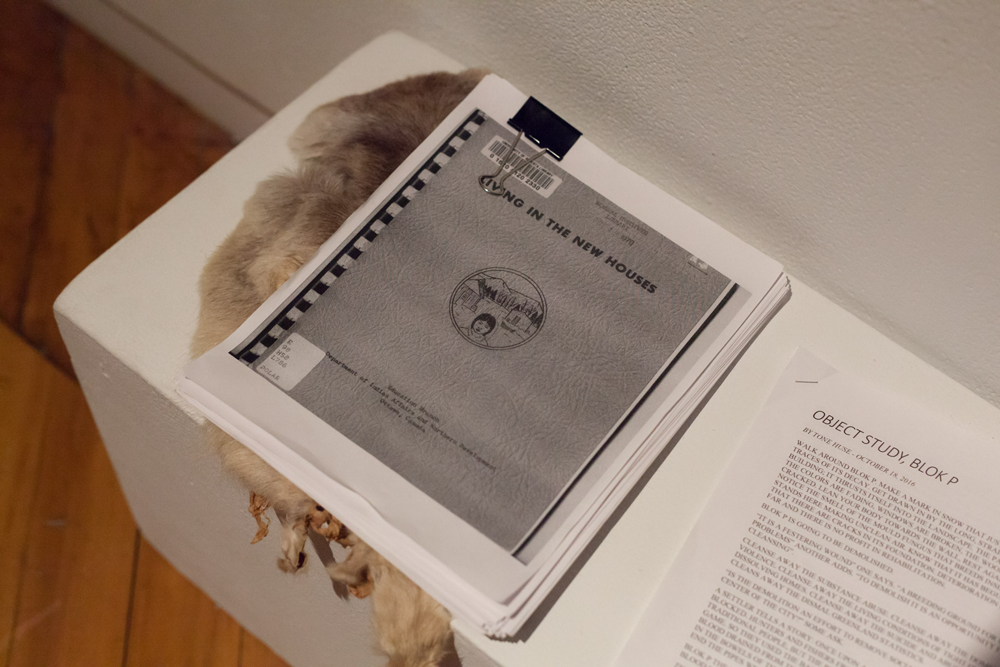

The Canadian Pacific Railway is hardly the only structure, physical or institutional, to displace belonging. In 1970, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development published Living in New Houses; an offensively childish manual detailing ways Inuit people might dwell (but not necessarily belong) in government-owned homes in the North. Architect and artist Joar Nango engaged this document in the exhibition “Folding Forced Utopias, for you,” up recently at Gallery 44.

Joar Nango, Folding Forced Utopias, for you (installation view), 2016. Courtesy Gallery 44. Photo: Jocelyn Reynolds.

Joar Nango, Folding Forced Utopias, for you (installation view), 2016. Courtesy Gallery 44. Photo: Jocelyn Reynolds.

Nango’s reframing of Living in New Houses prompts the question: What does it mean to locate belonging in a place the government has deliberately made inhospitable? “The government is the owner of the house…Eskimos rent houses from the government,” reads a page from the document Nango has transferred onto sealskin.

Joar Nango, Folding Forced Utopias, for you (installation view), 2016. Courtesy Gallery 44. Photo: Jocelyn Reynolds.

Joar Nango, Folding Forced Utopias, for you (installation view), 2016. Courtesy Gallery 44. Photo: Jocelyn Reynolds.

Also produced in the government document, and reproduced on Nango’s sealskin, is an instructional image of an Inuit woman organizing a storage cabinet. Disturbingly Ikea-like, the image is similar to other storage typologies illustrated in Living in New Houses, described as “A Place for Everything.” A place for everything, it seems, even for you? Yet belonging is more than just occupying a place.

Nango’s video Nomads Won’t Sit Still for Their Portraits, shown late last year at iNuit Blanche in St. John’s, tours a Mongolian nomadic settlement floating above a modern city. The glowing lights of apartments and office buildings appear like stars in the distance while barking dogs echo behind the narrator’s words: “Dwelling is tied not to a territory, but to a journey.”

All this dwelling on dwelling evokes Martin Heidegger’s 1951 essay “Building Dwelling Thinking.” Heidegger delivered an early version of the paper at a conference on social housing following the Second World War. Speaking to a crowd of architects, urban planners and government officials, he argued dwelling and belonging were intimately tied up with what it means to be human. And, particularly, what it means be with others.

Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko, A Kind of Loud Roar, 2017. Installation view. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko, A Kind of Loud Roar, 2017. Installation view. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Heidegger’s poetic meditations on dwelling narrate the video A Kind of Loud Roar, produced by the collective of Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko, also featured in Trinity Square Video’s “of movement and dwelling.”

In A Kind of Loud Roar, flames engulf the abandoned domestic architectures of the Lost Villages of southern Ontario—homes and communities that were expropriated, and later largely submerged, for the building of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950s. In appropriated archival footage, these residences burn like a Turner painting turned GIF. Here, any agency architecture had to frame dwelling or belonging is reduced to smoke, ash and rubble.

“It’s just a big home. That’s all it was,” remarks A Kind of Loud Roar’s disembodied narrator.

Drawing any line—a road, a railway or a wall—is an attempt to demarcate two supposedly stable conditions. It defines what is not, as opposed to what might be.

So it follows that home, as an ungraspable liminal space, is unable to be built, located, pointed to or mapped. Instead, it must be revealed through materials beyond brick, stone and board—whatever those may be.

There really is no place like home. And, as a tangerine-tinted real-estate mogul begins to inhabit one of the most infamous houses while signing executive orders to draw even more lines, maybe the absence of any architectural attachment to belonging is okay. Because without these exclusionary structures, all we have left is each other.

Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko, A Kind of Loud Roar (installation view), 2017. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko, A Kind of Loud Roar (installation view), 2017. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.