Equinox Gallery, Vancouver

The anatomy of art receives nightmarish (and scrupulous) attention in Ben Reeves’s new work. Taking his inspiration from Thomas Eakins and Tom Thomson, Reeves zooms in to assess a dimension of art normally hidden from the human eye. His charcoal, pencil and ballpoint-pen drawings are relief maps of masterly moments in painting. Indeed, these works aim to spell out something more intimate about the paintings that they pay homage to. Here is a level of neurotic assessment normally reserved for hair-splitting art critics.

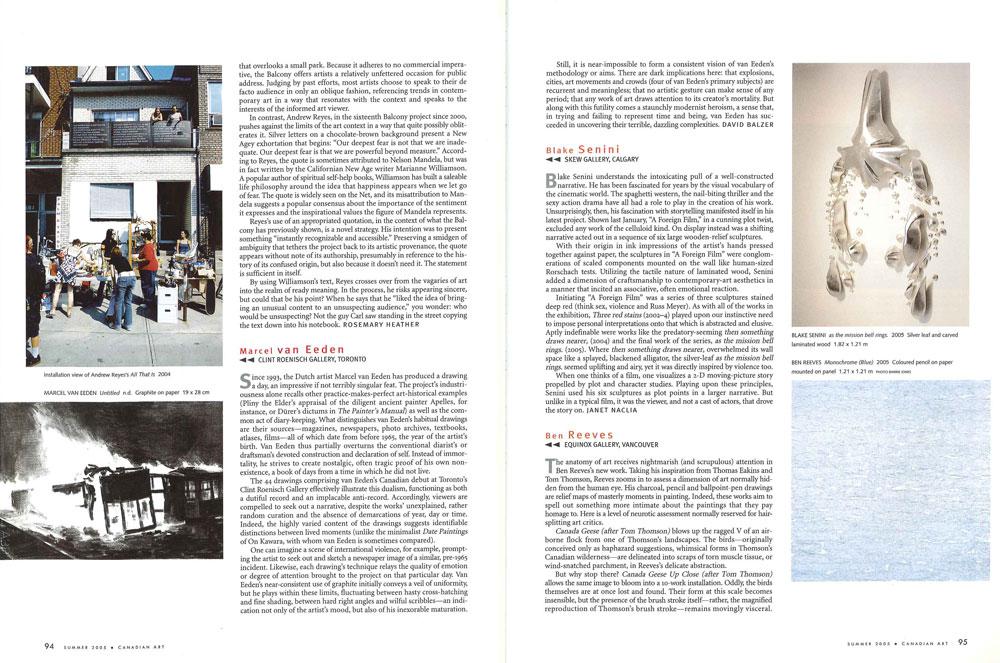

Canada Geese (after Tom Thomson) blows up the ragged V of an airborne flock from one of Thomson’s landscapes. The birds—originally conceived only as haphazard suggestions, whimsical forms in Thomson’s Canadian wilderness—are delineated into scraps of torn muscle tissue, or wind-snatched parchment, in Reeves’s delicate abstraction.

But why stop there? Canada Geese Up Close (after Tom Thomson) allows the same image to bloom into a 10-work installation. Oddly, the birds themselves are at once lost and found. Their form at this scale becomes insensible, but the presence of the brush stroke itself—rather, the magnified reproduction of Thomson’s brush stroke—remains movingly visceral.

What sort of relationship does Reeves propose to create with Thomson, with Eakins? And would they approve? (And does Reeves care?) Thomas Eakins himself argued, “The Greeks did not study the antique.” On art inspired by antiques he quipped, “At best, they are only imitations, and an imitation of imitations cannot have so much life as an imitation of nature itself.” What do we have, after all, when we mine another’s art and deign to make art from what we find there? Does Reeves eschew something elemental by retreating into minutiae?

If Reeves is attached to the antique, he uses that position to act as an equalizer. His obsessions over the anatomy of things, the grain of a brush stroke or the parts of a machine, become signifiers for the atomic, the cellular level at which other mysteries abide. But can a Mozart sonata be frozen into single notes? At what level does the critical, dissecting eye hit the ne plus ultra of insight?

This is a review from the Summer 2005 issue of Canadian Art.