Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto

Beginning with photos of human remains taken in the 1980s in the Sicilian catacombs, Jack Burman has long chased his dark muse in an extended inquiry into death. Going where only pathologists and anatomists normally go, he looks at the body cut open and exposed. Approached reverentially, like a sacred relic, the inside of the body is at once charnel and an analogue for the inner life. Abject death is transmogrified by means of glorious preservation. But death is a spectre best glimpsed out of the corner of one’s eye, so in looking at his photos of bits and pieces of human remains, the viewer lapses nervously into questions. Who were these people, now just a head, a severed hand, a heart with the arteries and veins exposed and bright with dye? How did they die? To pass out of this world unclaimed, as these people did, is a haunting prospect. Three days of anonymity in the morgue and you too could end up a truncated cadaver on a pathology table.

How, especially, do we account for the lovely serenity of the decapitated heads? Barthes says that the underlying subject of every photo is death, but it’s double indemnity: a person dies, is semi-resurrected by being preserved, then as good as dies again by virtue of being forgotten in a moribund collection. A reclamation project on several levels, Burman found, in Budapest, heads mummified in the 1930s that had not been touched since the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. In Córdoba, Argentina, he worked in a medical school, photographing specimens from the 1920s and 30s.

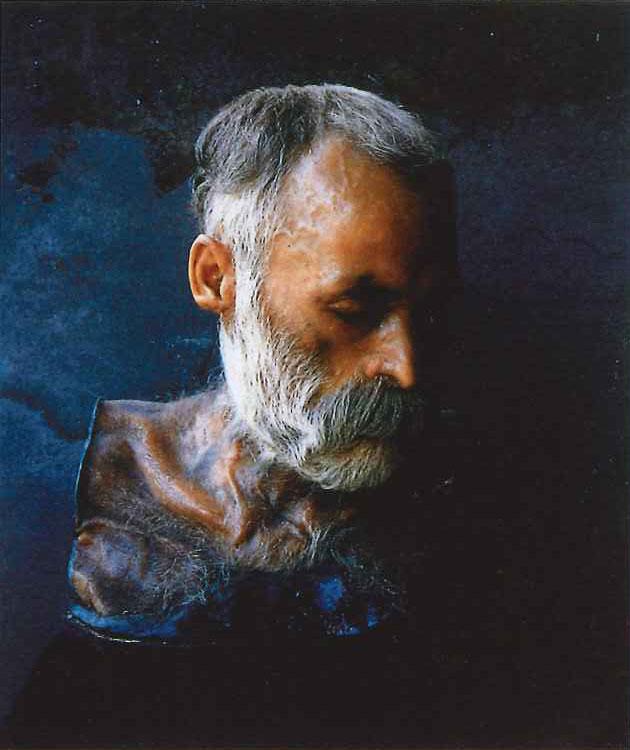

Uncannily evocative are the heads prepared by that school’s anatomist, Dr. Pedro Ara, who also preserved the remains of Evita Perón. Thanks to a technique that infused the remains with molten paraffin, the skin is smooth and lustrous, the eyelashes and hair delicate and soft, the colour still fresh. Eyes are lowered, heads flung back or lolling, as if in sleep, the illusion compromised but not destroyed by the cutting that these cadavers have undergone. To make up for the indignity, they have been mounted upright on bases, looking for all the world like Greco-Roman busts of dignitaries. The only head with a chronicled history is that of a gaunt, bearded man, aesthetic as a saint, who lived in the courtyard adjacent to the medical school where Dr. Ara practiced. Nearing death, the man offered his body for preservation and his wish was honoured. Looking at these bodies, more human sculptures than specimens, you wonder what exactly the good doctor was demonstrating.

Printed exquisitely, Burman’s vanitas images sing a song of death with a counter-melody that celebrates life. Far from eliciting repugnance, you can almost hear them hum “do not be afraid.”

This review is from the Fall 2004 issue of Canadian Art.

Jack Burman, Argentina #11, 2001

Jack Burman, Argentina #11, 2001