Exit Art, New York

“Terrorvision” is a presentation of a theme—the experience of terror. It covers everything from a near-death experience on the operating table to the trauma of breast cancer; however, its focus is the political use of terror by governments.

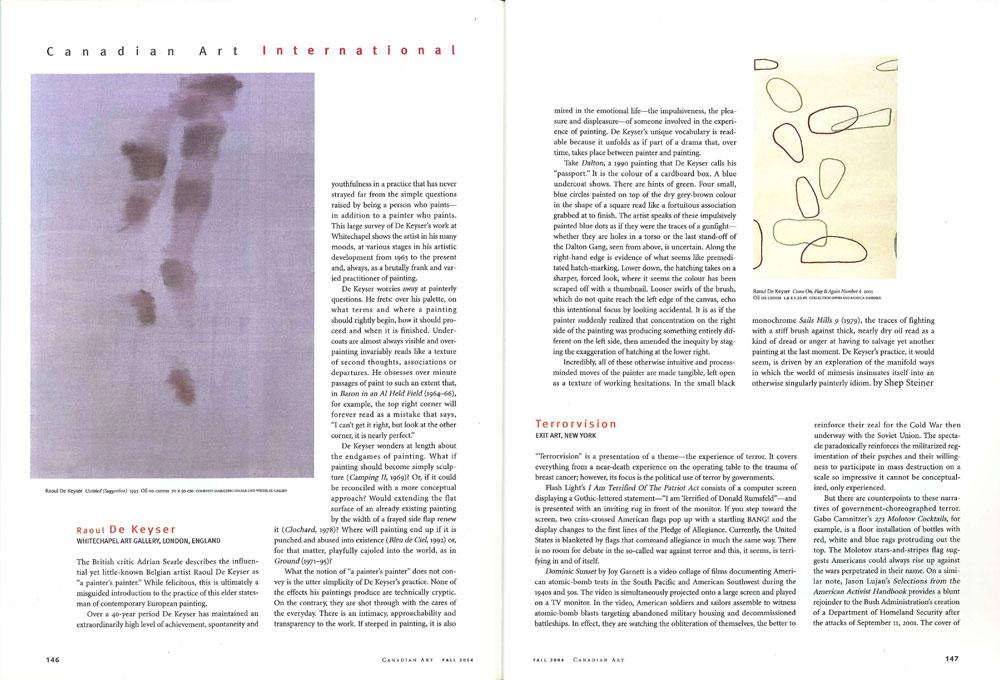

Flash Light’s I Am Terrified Of The Patriot Act consists of a computer screen displaying a Gothic-lettered statement—”I am Terrified of Donald Rumsfeld”—and is presented with an inviting rug in front of the monitor. If you step toward the screen, two criss-crossed American flags pop up with a startling BANG! and the display changes to the first lines of the Pledge of Allegiance. Currently, the United States is blanketed by flags that command allegiance in much the same way. There is no room for debate in the so-called war against terror and this, it seems, is terrifying in and of itself.

Dominic Sunset by Joy Garnett is a video collage of films documenting American atomic-bomb tests in the South Pacific and American Southwest during the 1940s and 50s. The video is simultaneously projected onto a large screen and played on a TV monitor. In the video, American soldiers and sailors assemble to witness atomic-bomb blasts targeting abandoned military housing and decommissioned battleships. In effect, they are watching the obliteration of themselves, the better to reinforce their zeal for the Cold War then underway with the Soviet Union. The spectacle paradoxically reinforces the militarized regimentation of their psyches and their willingness to participate in mass destruction on a scale so impressive it cannot be conceptualized, only experienced.

But there are counterpoints to these narratives of government-choreographed terror. Gabo Camnitzer’s 273 Molotov Cocktails, for example, is a floor installation of bottles with red, white and blue rags protruding out the top. The Molotov stars-and-stripes flag suggests Americans could always rise up against the wars perpetrated in their name. On a similar note, Jason Lujan’s Selections from the American Activist Handbook provides a blunt rejoinder to the Bush Administration’s creation of a Department of Homeland Security after the attacks of September 11, 2001. The cover of the handbook features a photograph of four armed Navajo warriors and the slogan “Fighting Terrorism Since 1492.” And its pages of how-to descriptions on topics such as “Sniping” and “The Use of Land Mines” are taken straight from a U.S. Army training manual. Terrorism and the fight against it have a history, and this history can complicate the present and the past.

The ramifications of terror often escape the control of the terrorists themselves, and this is the subject of Canadian artist Jayce Salloum’s three-part Untitled video series. Salloum’s arresting videos deal with destruction visited upon people through terrorism, the terms of resistance to it and the hope of recovery from it. Migrants, refugees, asylum seekers and residents from cities in the former Yugoslavia (including Serbia) reflect on the processes of dehumanization that tore apart their communities in the course of the civil war. The interviews are threaded through with astute observations of the use of military force by governments to reinforce territorial agendas. It would seem that nationalism demands terrorism and the renunciation of terror demands the denunciation of nationalism—peace in the former Yugoslavia is achieved in each individual refusal to play the terrorist’s game and take sides. There is no recovery from the massacre of Palestinians in two Lebanon-based refugee camps during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, but by superimposing footage of running streams, blooming flowers and passing clouds over camp scenes, Salloum suggests nature can obliterate terror regardless. An interview with a female Lebanese resistance fighter who spent ten years in an Israeli prison reveals that torture is powerless to control the human spirit. Moments of endurance, capitulation, humiliation, fear and pain never shook her sense of self or the political consciousness that saw her through her confinement.

“Terrorvision” is resolutely humanist in its assertion that there is more to terror than the act of terrorism. If we are ever to escape from the cycle of conflict that feeds terrorism, this exhibition is a good place to start.